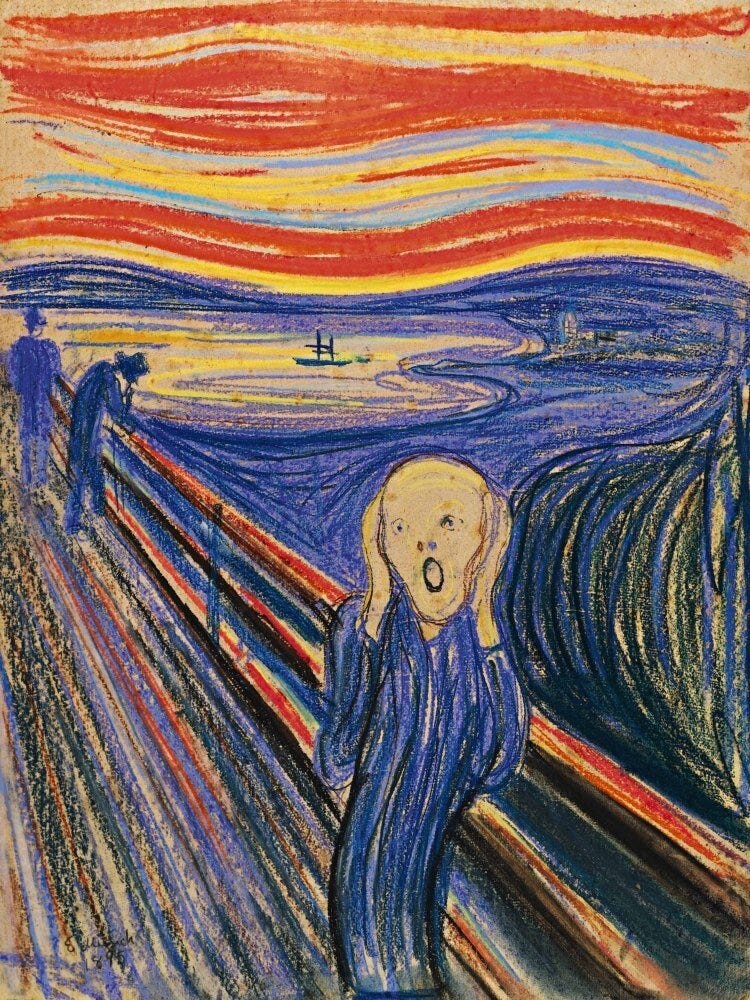

Fear is a response to a particular object-of-fear: an automobile accident, a debilitating illness, a lunatic with an axe. But dread or anxiety is less anchored, more diffuse. It’s an engulfing state rather than a discrete adrenalin rush. We typically use the words “fear,” “dread,” and “anxiety” interchangeably—and they do share a family resemblance—but they denote quite different experiences.

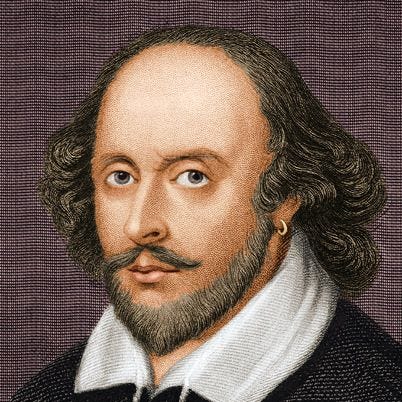

The nineteenth and twentieth century existentialists made much of this kind of dread—famously called “angst” by Kierkegaard—seeing it as a response to the vertiginous experience of radical freedom (an awareness, says Kierkegaard, of the possibility of possibilities). But Shakespeare nailed it three centuries earlier in several of his plays. In Richard II, which offers a brilliant portrait of a man who provokes in us both contempt and genuine pity, he gives a nearly clinical description of angst.

Richard has left for an ill-fated expedition to Ireland. At his departure, Queen Isabella experiences a diffuse uneasiness which unsettles and perplexes her. One of her courtiers tells her to calm down, that she's just suffering from overwrought “conceit,” by which he means “imagination.” “'Tis nothing but conceit, my gracious lady,” he patronizingly says. But Isabella knows better.

“Conceit is still derived

From some forefather grief. Mine is not so,

For nothing hath begot my something grief—

Or something hath the nothing that I grieve.

'Tis in reversion that I do possess,

But what it is that is not yet known what,

I cannot name. 'Tis nameless woe, I wot.” (Act 2, Sc. 2: 35-41)

Fearful imaginings of specific future threats usually spawn or “forefather” anticipatory grief, but this isn't what's happening to Isabella. No specific threat—“nothing”—has begotten her grief. Her “something grief” comes from nothing—or, put another way, if there is an antecedent cause of it, that “something” has embedded within it an inexplicable “nothing.” The usual process has been reversed (“reversion”): the experience of grief precedes any discernible cause. This bestows on her grief an uncanny sheen that she “cannot name,” can neither understand nor label. It is a “nameless woe.” And this is precisely what Kierkegaard will call angst.

Brilliant. As always when it comes to Shakespeare.

###

Kerry: Reading your insightful account of Shakespeare’s dramatic portrayal of “angst,” has given me a mild case of morning angst! Still, it was worth it. Cheers!