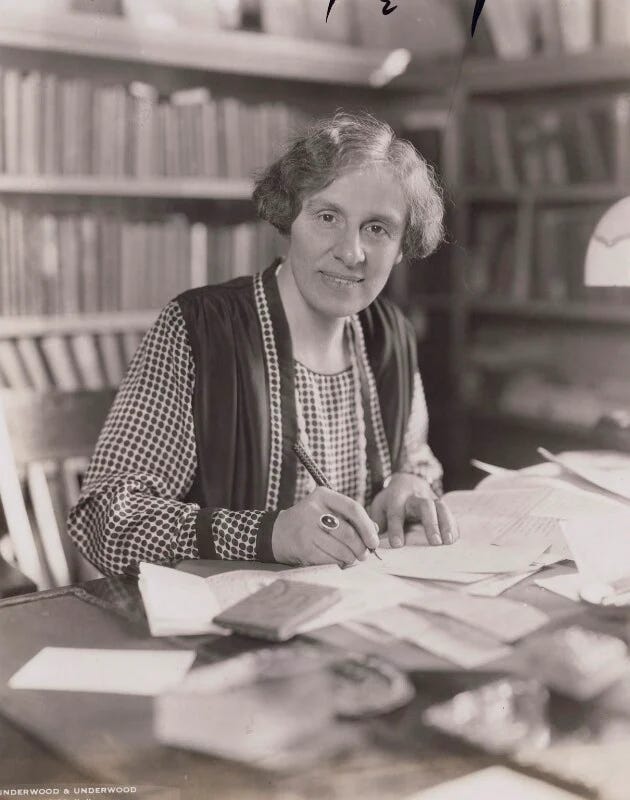

I continue work on my book on Maude Royden (1876-1956), the extraordinary British suffragist, pacifist, preacher, social reformer, and champion of women’s ordination. It’s appropriate that today, when my area of central Pennsylvania is being buffeted by heavy rains and high winds from Hurricane Debbie, I should be working on her 1916 pamphlet Women and the Church of England. It’s a breathtakingly powerful, hurricane-force denuciation of the Church’s oppressive and hypocritical insistence that women in her day take back seats—WAY back seats—when it came to both governance and holy orders. Most bishops wouldn’t even allow women to handle the collection plate or ring sanctus bells during worship, much less preach.

The Church of England finally ordained women on 12 March 1994, twenty years after the Episcopal Church and nearly four decades after Royden’s death. But there are still Christian denominations out there that treat women as untouchables.

Royden was a pioneer in so many ways. She deserves to be remembered and honored.

Here’s a particularly hard-hitting selection from her magnificent Women and the Church of England.

***

From top to bottom the Church is officered by men, and—incredible to relate—it is not even permitted us to ask why! The mere question, “Why should not women be admitted to holy orders?” causes some Churchmen to cry out and cut themselves with knives, while others, more reasonable, assure us that there are indeed reasons, but of a character so “fundamental” as to prohibit their being put into words. With this it is expected that women—women of the twentieth century—will be content! But, alas! “Somehow this comment does not now satisfy.” We desire reasons, and it seems to us nothing but a comedy to suggest that this desire is monstrous, and that no such question should be so much as discussed by the people whom it most intimately concerns. Where, then, have these gentlemen who deny us lived? In what little island of thought have they been segregated from the contagion and movements of modern life, that they honestly believe they can by loud shouting and abusive language silence the demand for reasons when any great monopoly is on its defense? It is possible that women have not the vocation for the priesthood; but is it not possible to persuade them that they commit a crime when they raise the question and ask for an answer. Nor will they consider their doing so as a “conspiracy.”

The exclusion of women from all ranks of the priesthood is paralleled by their exclusion from nearly all other offices. Deacons, choristers, churchwardens, acolytes, servers, and thurifers, even the takers-up of the collection, are almost invariably men. If at any time not one male person can be found to collect, the priest does it himself, or, after a long and anxious pause, some woman, more unsexed than the rest, steps forward to perform this office. In one church, I am told, it was the custom for collectors to take the collection up to the sanctuary rails, till the war compelled women to take the place of men, when they were directed to wait at the chancel steps. In another it was proposed to elect a woman churchwarden, when the Vicar vehemently protested on the ground that this would be “a slur on the parish.” In another, the impossibility of getting any male youth to ring the sanctus bell induced a lady to offer her services. After anxious thought the priest accepted her offer “because the rope hung down behind a curtain, so no one would see her.” The propriety of women conducting the simplest of services or delivering an address from any part of the church excites in the mind of a section of the Church, not so much disapproval as hysterics. While everywhere women are gathering others together in halls, in drawing rooms, in cottages, to join in intercession for their country, their Church, their friends, it is still in almost every diocese impossible for them to meet in the house of God. While every platform in the country is open to them, and every cause welcomes their service as speakers, in the churches only men must be heard. The pilgrims who go out on a pilgrimage of prayer, which should begin and end in the church of every parish visited, must give their messages in the schoolroom instead, where a grown-up congregation accommodates itself as well as it can to the uneasy desks and chairs of children. Conventions are held, but as they are held in cathedrals and churches, no woman, though she be an “Archbishop’s messenger”—no woman, though she be indeed inspired by God—can take a part. If a reason is sought, it is conveyed in the answer, “The church is a consecrated place.” The modern woman does not find in this statement a reason. She finds in it an insult, perhaps the most comprehensive that could be offered to a human being.

In the same spirit a correspondent in a recent correspondence in the Guardian quotes with approval the rule that, at Mass, women are “not allowed near the altar.” Are there, then, “untouchables” in the religion of Christ after all? Were we wrong in supposing that in Him there is “neither Jew nor Greek, Male nor female, bond nor free”?

There were women standing near the Cross when Our Lord was crucified. Is the Cross less sacred than the altar? Or the crucifixion less sacred than the Mass? Or will our brothers in the Church of England give us some reason for this “perpetual insult to our personality” other than the assurance that we are unthinkably wicked to resent it, and that it rests on grounds too good to be put into words? We do resent it. We find it intolerable that while the veriest little ragamuffin of a boy may “serve” at the altar, women whom we revere as leaders, reverence as saints, are excluded. We find it a scandal that the most ignorant of young men may get up and admonish us out of the depth of his inexperience and unwisdom in the pulpit, while women at whose feet the world is willing to sit are treated as though it were a thing impossible that they should have a message from God or know the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. We know they have such a message, and like the rest of the world, we go where we may hear it. Why are the churches empty? Is it because they have too great an abundance of inspired speakers?

Our contention cannot now be answered by a quotation from St. Paul; for we know that that great apostle, if in one place he directed the Corinthians not to allow women to speak, in another, with equal clearness, told them what the women were to wear when they did speak. We know also that the quoter himself sets aside the authority he invokes whenever it seems reasonable to do so. The women of his church come unveiled, in spite of St. Paul. They wear gold and silver and braid their hair, in spite of St. Peter. They sit teaching in the Sunday School, in spite of the author of the Epistle to St. Timothy. They form public opinion on public platforms—even on church platforms—while bishops take the chair for them and priests sit in the audience. Is it not, then, a little comic—or shall I say a little late—to demand that women should yield a literal obedience to an authority so lightly set aside by their critics?

Or is it seriously contended that the literalism which we are assured is a grave error when applied to the Sermon on the Mount, becomes a duty when the speaker is one of incomparably less authority? Let us speak boldly. The great work of scholarship has set us all free from the bondage of the letter, and it seems to us an act of hypocrisy, conscious or unconscious, that men should seek to scare us, like children, with its ancient terrors. Do they suppose that women read no biblical criticism? Do they suppose that women, alone in an indifferent world, “abstain from things strangled and from blood,” as directed not by one apostle but by all of them together, blind to the fact that their brothers have “scrapped” these regulations long ago? Do they dream that we can worship this god whom they set up for us—a god who witnesses with complacency the “prophesying” of women in halls and schoolrooms, but is provoked to wrath if they prophesy in a church? Or who meticulously observes whether a chapel is “consecrated” (when a woman may say “There is none other that fighteth for us, but only Thou, O God,” but not “Give peace in our time, O Lord”) or merely “licensed” (when she may say either or both without scandal)? Or who is seriously concerned whether she enters the church with a hat or a veil or a bow or a wig or only her own hair on her head? This a god to worship? We cannot even respect him. We were not baptized into this religion of rules and of the letter, nor into Paul, nor Apollos, but into Christ. To this supreme Authority we appeal.

We find in the teaching of Jesus no suggestion of inequality between the sexes. On the only occasion on which He was challenged directly on this subject He is reported to have replied by demanding an equal standard from men and women. Elsewhere He appears to have ignored the traditional Jewish attitude towards women, by treating them just as He treated men. It is not possible to isolate any words of His from their context and to decide from their character or their tone whether they were addressed to women or to men. There is no trace of intellectual condescension in His words to women. There s no hint that a woman’s ideal must be different from a man’s, or her work, or her sphere. The parable of the talents is unaccompanied by any warning that if a woman has a talent for public speech, or the gift of leadership, or a genius for teaching, she will do well to bury it in a napkin. “His disciples marveled that He was speaking with a woman,” but He talked to her of the deepest religious truths, as He might have spoken to St. John. He shrank from the touch of none, He received all who truly desired to follow Him, His eye fell without reproach on those who at the last stood by Him on the Cross. What a world of difference between all this and the close and stuffy intellectual atmosphere of our churches! Between the Christ who appeared first to a woman on His rising from the tomb, and the Churchmen who forbid a woman to be “near the altar”!

And with this sense of difference in our minds, we women of the twentieth century appeal to the leaders of our Church to go forward. At first a leader in this as in other movements towards real democracy, the Church now has fallen behind and handed the torch to others. In public life, in the State and the municipality, in movements for social reform, in the Labor Movement as well as in their own movement, in non-Christian organizations often, women find a more generous recognition of their value, a greater readiness to work side by side with them, than they find in the Church. Is it wonderful that they choose to give themselves where they can do so most freely, and work where their work is least hampered by petty restrictions and insulting prohibitions? There was a time when religious work was almost the only avenue for a woman’s energies, but now the world is all before her where to choose. Are we wrong—we who are Churchwomen—in regretting even more for the Church than for the women their choice of other spheres of work than hers? “The ablest women of the day are not—with some notable exceptions—giving their lives in the direct service of the Church and, however valuable their service is to the nation, the loss of it to the Church is serious to contemplate.”[3] Is that not true? And is it not disastrous? The churches are still filled (if filled at all) largely with women. But the leaders have gone or are going, and the young do not come. “The Church for her own sake, for her members’ sake, and for the sake of those who through them might believe in God, should give every woman an opportunity of exercising all her gifts” (even if they be gifts of leadership—even if they be gifts of tongues). “No woman with her heart on fire to serve her generation according to the will of God should find her sphere more readily outside the Church than inside.” But women do find it so, and they go, not because they have ceased to love Christ, but because they do not find His Spirit in His Church, nor believe that in these petty restrictions, this grudging of opportunity, this insulting warning-off from holy places, there is anything in common with the spacious freedom of His teaching.

If we are wrong, let our error be shown to us with reason and not with abuse; but let those who oppose our claims realize that we do sincerely base them on the conviction that it is we and not they who in this matter have the mind of Our Lord. We have not made our claims lightly or unadvisedly, and claims sincerely made in the name of Christ should be treated with respect, even if they be mistaken.

If, on the other hand, we are right, let the Church take action.

###