A Flannery O'Connor Advent

Week 2: Peace, Tattoos, & God's Blue Pencil

“A story that is any good can’t be reduced, it can only be expanded.”1

“Parker’s Back,” one of Flannery O’Connor’s last and finest stories, reminds us that human lives are like texts. We, internal autobiographers all, struggle to transform our streams of experiences into harmonious and even artful stories. But we typically botch the job. We fiddle endlessly with fragments and snippets of plot as well as falsehoods and half-truths we tell ourselves about ourselves, and the result is often a patchwork that makes no sense. So when the time comes for us to lay down our pens once and for all, we exit as unfinished works. Our stories end before they’re completed.

E.O Parker, the eponymous hero of O’Connor’s tale, is obsessed with making his life a good story. Employing one of her shocking “visionary metaphors,”2 O’Connor tells us that Parker’s effort to write his life consists in covering the front of his body, the side he most easily sees, with tattoos. But what he’s eventually left with is a hodge-podge of images or texts that only serve to fragment his sense of self—his story.

“Parker would be satisfied with each tattoo about a month, then something about it that had attracted him would wear off. Whenever a decent-sized mirror was available, he would get in front of it and study his overall look. The effect was not of one intricate arabesque of colors but of something haphazard and botched. A huge dissatisfaction would come over him and he would go off and find another tattooist and have another space filled up. […] As the space on the front of him for tattoos decreased, his dissatisfaction grew and became general.”3

Fragmentation, O’Connor noted in one of her essays, is the hallmark of a bad story. It’s also the sign of a stunted, nonexpansive life.

Jesus knew this. That’s precisely why his gift of peace, the second Advent blessing, is so crucial. “Peace I leave you,” he said, “my peace I give to you.” (Jn 14:27)

When we think of peace, what typically comes to mind is the absence of conflict, war, or stress. But the biblical understanding of peace, the one Jesus offers, goes deeper.

In the Hebrew scriptures, שָׁלוֹם or shalom means wholeness, completeness, or fullness. In the Christian scriptures, its Greek parallel is εἰρήνη or eiréné, derived from the verb εἴρω or eirō: “to join,” “to tie together into a whole.”

Contrary to conventional wisdom, then, peace is more than an absence of conflict. It’s the opposite of fragmentation. It joins that which is broken; it ties together the loose and frayed strands of our stories. What Jesus offers is the gift of wholeness, the expansion of our constricted lives into the beautifully complex harmonies they’re intended to be.

The Renaissance biographer and gossip Giorgio Vasari wrote that God is the first Artist. True. But God’s also the first Editor, stepping in with the blue pencil of grace to clean up the messy texts we’ve made of our lives. As St. Paul says in the epistle appointed for this second Sunday of Advent,

“I am confident of this,

that the one who began a good work in you

will continue to complete it.” (Phil 1:6)

Or as O’Connor puts it, “in us the good is something under construction.”4

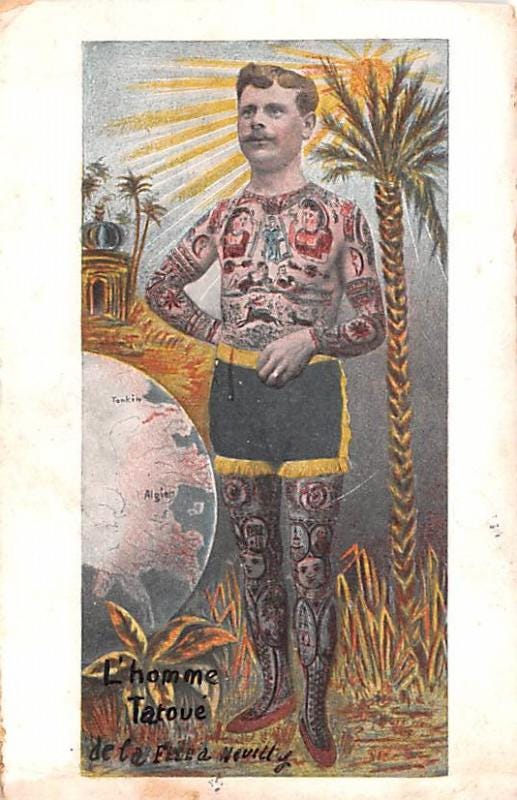

I said earlier that Parker is obsessed with making his life a good story. But that’s not entirely accurate. Were that description offered him, he’d probably blink in bewilderment. He’s a simple man. What he does know, though, is that he hungers to recapture an experience that came to him when he was a fourteen-year-old “heavy and earnest” boy, “as ordinary as a loaf of bread.” At a traveling fair, he saw a man “tattooed from head to foot […], a single intricate design of brilliant color.”5 The effect on him was electric.

“Parker had never before felt the least comfortable motion of wonder in himself. Until he saw the man at the fair, it did not enter his head that there was anything out of the ordinary about the fact that he existed. Even then it did not enter his head, but a peculiar unease settled in him. It was as if a blind boy had been turned so gently in a different direction that he did not know his destination had been changed.”6

Gazing on the intricate and beautiful mosaic of the tattoo artist’s body, the young Parker experiences for the first time the sheer wonderment of existence (an uncanny but revelatory moment all of us need to experience!) accompanied by an awakening of yearning—a “peculiar unease”—for something he can’t quite articulate.

What Parker longs for, of course, is what we all want—even if, like him, we can’t name it: a life of shalom, of fruitful, fulfilling expansiveness. We want to be whole, not chaotically fragmented. In Parker’s naivete this yearning gets translated into a fixation to imitate the tattoo artist. But no matter how much he tries to turn his body into a mosaic in which every tile coheres with others to form a seamless text, he remains restlessly unsatisfied.

Years after he saw the tattoo artist, Parker experiences a second dark flash of inspiration whose significance he again doesn’t quite grasp: he has “the haloed head of a flat stern Byzantine Christ with all-demanding eyes” tattoed on his hitherto unmarked back. Parker thinks his motive is to please his shrewishly evangelical wife. But in fact the image exerts for him an irresistible but mystifying “subtle power.”7 After getting the tattoo, and following a drunken spree which lands him in a filthy alley, Parker gains more clarity about the image’s power.

“Parker sat for a long time on the ground in the alley behind the pool hall, examining his soul. He saw it as a spider web of facts and lies that was not at all important to him but which appeared to be necessary in spite of his opinion. The eyes that were now forever on his back were eyes to be obeyed. He was as certain of it as he had ever been of anything.”8

Parker’s past life, with all its frustrated searching for that something for which he yearned but couldn’t name, was in fact the necessary vehicle to bring him to the point where he can begin to find the peace—the wholeness—he craves. He at last knows he lacks the skill to write his story on his own. He needs the guiding gaze of the Editor.

It’s important not to miss the spiritual significance of O’Connor’s “the eyes that were now forever on his back were eyes to be obeyed” line. On a first reading it sounds rather oppressive, conjuring up the image of a divine Big Brother constantly glaring over one’s shoulder. But remember that the Latin word for obedience actually suggests a kind of listening: ob + audire = “towards” + “to hear.”9 O’Connor’s implication is that Parker has reached a point in writing his life story where he’s finally able to listen to the restorative counsel of God, willing to consider Jesus’s editing suggestions. His hand, hitherto unsteady and uncertain, only able to scribble disjointed scenes symbolized by his patchwork of tattoos, is now guided by grace.

Like all of O’Connor’s heroes, the road that now lies before Parker won’t be easy. In fact, we last see him sobbing in the rain and clinging to the trunk of a tree, his tattooed back covered in welts from a beating by his enraged wife. (“Idolatry!” she screams when he shows her his Christ-tattoo. “Idolatry! Enflaming yourself with idols!”10) As O’Connor characteristically observes in one of her letters, “This notion that grace is healing omits the fact that before it heals, it cuts with the sword Christ said he came to bring.”11 But Parker’s wife is more right than she knew: he is enflamed now, ready to write his life, under the guidance of God’s editorial gaze, in fiery letters.

This is the beginning of peace, the second blessing of Advent: wholeness, harmony, expansiveness, completion, fulfillment.

Next Week: A Flannery O’Connor Advent - Advent 3, Joy

Flannery O’Connor, “Writing Short Stories” in Manners and Mystery: Occasional Prose (ed) Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970), p. 102.

“Visionary poetics” and “visionary metaphors” are coinages by Edward Kessler to signify O’Connor’s use of shockingly unexpected images. See his excellent Flannery O’Connor and the Language of Apocalypse (Princeton University Press, 1986).

“Parker’s Back,” in Flannery O’Connor, The Complete Stories (New York: Noonday Press, 1999), p. 514.

“Introduction to a Memoir of Mary Ann,” in Manners and Mystery, p. 226.

“Parker’s Back,” p. 512.

Ibid., p. 513.

Ibid., p. 522.

Ibid., p. 527.

St. Benedict beautifully opens his Rule with Obsculta, O fili, praecepta magistri, et inclina aurem cordis tui: “Listen, O son, to the master’s instructions and incline the ear of your heart to them.” Obsculta (rendered ausculta in some manuscripts), the imperative form of “listen,” shares a common root with obaudire. Benedict’s opening sentence subtly gets across the close connection between listening and obeying.

Ibid., p. 529.

O’Connor to “A” (1 October 1960), The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor (ed) Sally Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979), p. 411.