A R.S. Thomas Advent

Week 1: To Wait is to Hope

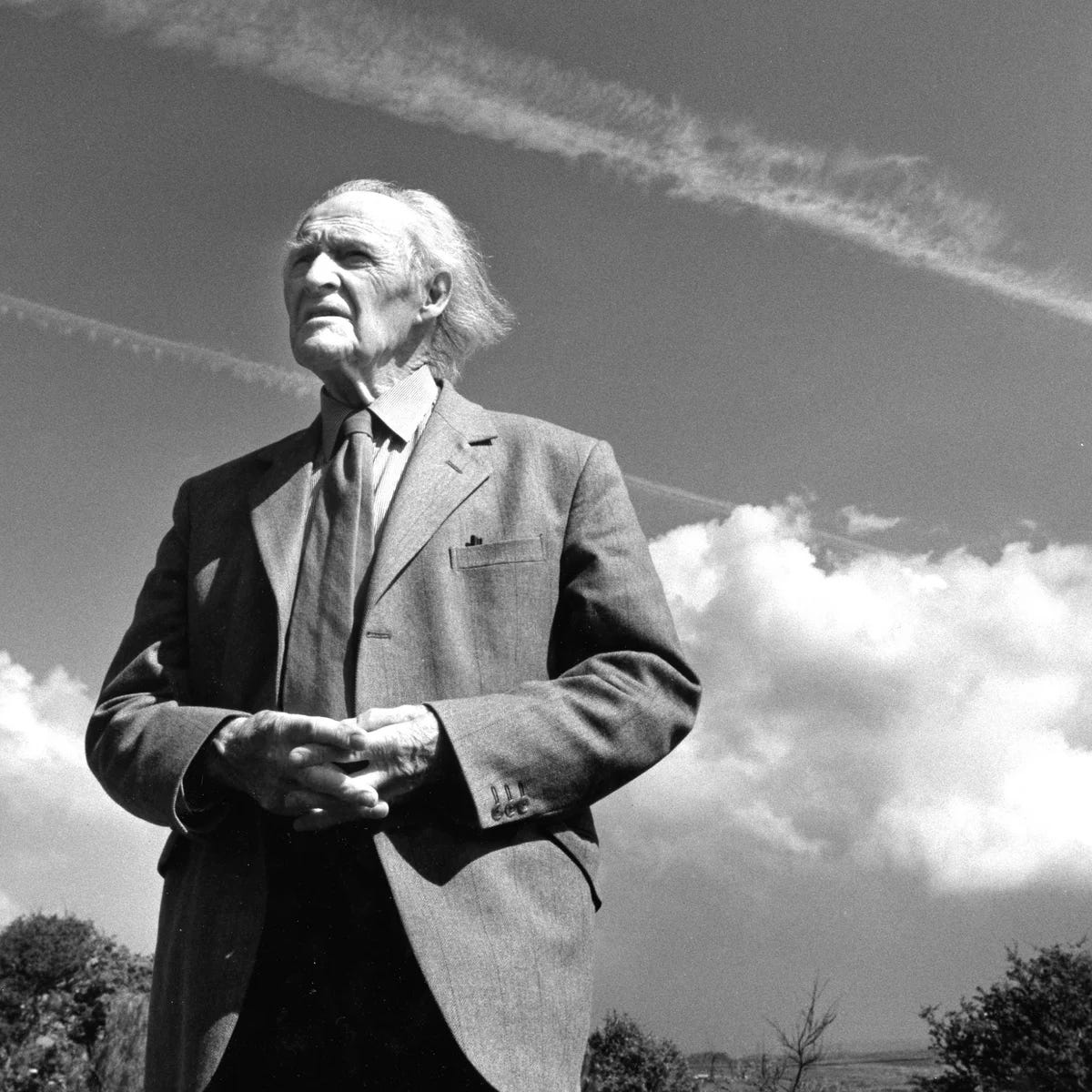

[The Pupil in the Blank Face: R. S. Thomas’ Poetic Search for God offers an overview of Thomas’ poetic vision. Readers unfamiliar with his work might find it a helpful prelude to this series. But each of the four Advent meditations, beginning with this one, may, I trust, be read independently of it.]

Moments of great calm,

Kneeling before an altar

Of wood in a stone church

In summer, waiting for the God

To speak; the air a staircase

For silence; the sun’s light

Ringing me, as though I acted

A great rôle. And the audiences

Still; all that close throng

Of spirits waiting, as I,

For the message.

*

Prompt me, God;

But not yet. When I speak,

Though it be you who speak

Through me, something is lost.

The meaning is in the waiting.1

Later, Not Now

Paul of Tarsus, that ego-haunted zealot, was confident that the cosmos itself shared his own restless need for salvation. All creation, he asserted, groans and travails for the final coming of God. The image lodged in his fellow disciples’ imaginations, and some years later one of them described in wearisomely baroque detail where he fancied the cosmic labor pains were headed: an explosively rejuvenative Endtime that vanquishes every fear and dries every tear.

This ancient Pauline/Johannine drama is the scriptural tail that too often wags the Christian understanding of hope. It paints hope as the tensely yearning, high-alert, groaning-and-travailing anticipation of a dramatic future finale in which everything that’s broken in the here-and-now is set right. Whether one speaks eschatologically or personally, the present becomes only the interlude between the First and Second Coming. Jesus appearing at some future time to wave the righteous into the restored Eden: that’s hope’s proper target. Maranatha!

Ausculta

In “Kneeling,” R.S. Thomas gently reminds us that there’s another way to envision hope, one that doesn’t disparage the present by focusing so obsessively on the future. Hope for him is a kind of waiting, but not for something that is to come. Hope, for Thomas, isn’t future-oriented. I know; this seems to violate the very meaning of the word. But wait.

The seventh-century Rule of Benedict opens with a fine Latin term: Ausculta! It means both “listen!” and “obey!”2 This double-edged counsel beautifully captures the mood Thomas wants to convey in his poem. He imagines himself in a bodily position, “kneeling before an altar / of wood in a stone church,” that suggests yielding, submitting, acknowledging subordination. But as the poem continues, we learn that the kneeling is also a posture of focused receptivity to the numinous. The moment’s “great calm” becomes a Jacob’s Ladder invitation to deep listening: “the air a staircase / For silence.”

For a brief second, his focus wavers. Thomas nearly succumbs to the all-too-human egoic temptation to fancy he’s the spotlit star of the moment—“the sun’s light / Ringing me, as though I acted / A great rôle”—and accordingly stirs himself to perform, to fill the silence with savory burnt offerings of appropriately pious words. “Prompt me, God.” Remind me of my lines. Open my lips and my mouth shall proclaim your praise.

But then it strikes him: in moments like this, words are paltry things. They always fall short. In fact, they actively get in the way. Even if they’re genuinely prompted by God (which most often they probably aren’t), “something is lost” in the fallible transmission of them. What’s lost? The nexus of calm, silence, light. The clarity of perception. The possibility of insight. So better to stay quietly kneeling before the altar and the ethereal staircase, swallowing ego along with words.

Better to wait, because “The meaning is in the waiting.”

Now, Not Later

But what does this gnomic conclusion suggest?

Thomas isn’t telling us to wait for meaning, to glide over the significance of the present because fixated on the hope of something-to-come. This is to take a page from the Pauline/Johannine playbook. No. Instead, he says, the waiting is itself the meaning.

The English word “wait” enjoys a long lineage. Frankish wahton, Old North French waitier, Dutch wacht, Old High German wahhon, and Old English wacian: they all mean “to watch” and “to be wake.” Thomas’ “meaning is in the waiting” signifies watching and being awake here-and-now to the Divine Presence, not some groaned-and-travailed future.

We need, he suggests, to re-envision hope. It isn’t future-oriented. It’s Presence-oriented, and that means it’s now-oriented. Whenever we wait—whenever we watch and are awake in and to the moment—we are in hope.

Entering into this state of hope-receptivity demands exactly the state of being Thomas evokes in “Kneeling”: calm stillness, silence, patience, pellucidity, humility, reverence. To hope in this way is to remain poised in the present, to cease grasping after the future or dragging in prayers from the past, because God is “in” neither of those artificial places. God is the Eternal Now. First Coming, in-between time, Second Coming: these are but human attempts to slice up the Now in digestible temporal bites. Let them go. Then you can experience hope.

What the Cosmos Really Does

There’s another thing Thomas reveals about hope. He tells us that despite being alone before the chapel altar, he senses the company of “all that close throng / Of spirits waiting, as I.”

Who belongs to that throng to which Thomas feels himself so companionated? I believe it must be no less than the entire cosmos itself. And if that’s so, we have an image to replace Pauline labor pains. The universe isn’t sweatily groaning and travailing for the future coming of the Lord. The Lord’s already here. So the cosmos simply breathes, gently and calmly mindful of the Presence. It watches, it wakes, it inhales and exhales the Eternal Now. Kneeling before the altar in that deserted chapel, Thomas aligns himself with this universal respiration.

The spiritual gift offered us in the first week of Advent is hope. Over the centuries, we’ve draped it in a richly embroidered tapestry of legend, myth, and story. The tapestry is precious, and I don’t for a moment recommend stowing it away in a dusty attic. But poets like Thomas (not to mention the apophatic mystics among us!) occasionally peek behind the tapestry and discover a deeper meaning of hope, one unadorned with the artificial coloring of tradition.

To the rest of us, this re-envisioning of hope may seem uncomfortably stark or confusingly paradoxical. But that’s because we’re thinking about it rather than actually experiencing it. Those who have done both realize, as Thomas suggests, that we are most genuinely in hope when we calmly, serenely, and wakefully exult in the present moment, not agitatedly strain towards the future. Hope is about now, not later, and this insight lays the foundation for Advent’s three subsequent spiritual gifts of peace, joy, and love.

Next Week. Advent 2: The Peace of Crumbled Manna. Poem: “The Moor”

“Kneeling,” in R.S. Thomas, Collected Poems, 1945-1990 (London: Phoenix Press, 2001), p. 199.

In his critical edition of the Rule, translator Justin McCann notes that it’s only recently that some editors have favored deposing the Prologue’s traditional “ausculta” with the Late Latin variant “obsculta.” Neither he nor I find the substitution compelling. See his The Rule of St. Benedict in Latin and English (Eastford, CT: Martino Fine Books, 2019), p. 164.