“I have no God,” Barabbas answered. The Roman seemed surprised. “But I don’t understand,” he said. “Why then do you bear this ‘Christos Iesus’ carved on your disk?” “Because I want to believe,” Barabbas said, without looking up. —Pär Lagerkvist1

“The world is a closed door. It is a barrier. And at the same time it is the way through.” —Simone Weil2

You can’t will yourself to believe something you think is simply unbelievable. You may want to believe it; you may positively long to do so. But wanting to believe isn’t the same as genuinely believing. Neither is acting as if one really believes.

This truth is nowhere more unhappily illustrated than by those who long to believe in God but just can’t square it with what they’ve been taught about the world. Our increasingly secular ethos encourages skepticism. (Along the way, it also fuels the reactive fundamentalist craziness which causes sensible people to further distrust religion.) Nonetheless, yearning for a transcendent Source endures. Consequently, many persons find themselves in a frustrating in-between place of wanting to believe but not being able to believe.3 It’s one of the fundamental tensions of the modern age.

Metaxú: The Human Condition

The philosopher and historian Eric Voegelin, taking his cue from a single line in Plato’s Symposium, made much of the human experience of in-betweenness or metaxú (μεταξύ). (Voeglin’s critics contend he made too much of it.) The in-between dimension of existence reveals itself in many ways, according to Voegelin, but perhaps the most fundamental one is our bipolar awareness of the finite/material and the infinite/spiritual: we dwell in a material world, but catch glimpses in and through it of that which transcends it. This in-betweenness creates in us a state of existential tension. We’re like da Vinci’s Vetruvian Man, stretching to make contact with both worlds but never fully grasping either.4 This, says Voegelin, is the human condition.

Depending on personal temperament and cultural climate, in-between glimpses of the infinite can either be embraced as meaning-laden revelations or dismissed, even if only reluctantly, as foggy wishful thinking. The glimpses, as Simone Weil says in her own reflections on metaxú, can be a way through or a barrier. If the former, in-between tension veers in the direction of hope and expectation. If the latter, one of two things can happen. The first is that sensitivity to the possibility of Something beyond the here-and-now fades away—we become what the philosopher Charles Taylor calls “buffered selves,” ideologically barricaded from the transcendent.5 The second is that the frustration of those who yearn to believe but can’t only intensifies. Like Vetruvian man, they stretch and stretch but never make contact.

This is the situation in which the protagonist of Pär Lagerkvist's novel Barabbas finds himself.

Two Powers and the In-Between

In many ways, Swedish author Pär Lagerkvist (1891-1974), like his character Barabbas, is a man who wants to believe but can’t. Raised in a pious family, he moved away from faith in his teens. But he retained a nostalgia for it that comes across in many of his novels. Awarded the Nobel Prize in 1951 for Barabbas, Lagerkvist followed it up with several other tales focused on the human yearning for God: The Sibyl (1956), The Death of Ahasuerus (1960), Pilgrim on the Sea (1962), and The Holy Land (1964). Together they paint a more or less unified portrait of the human condition of in-betweenness.

In the four gospels, Barabbas is the criminal (or “revolutionary,” according to the evangelist John) who at Passover is pardoned instead of Jesus.6 The Bible tells us nothing about his subsequent life.

That’s where Lagerkvist picks up the story.

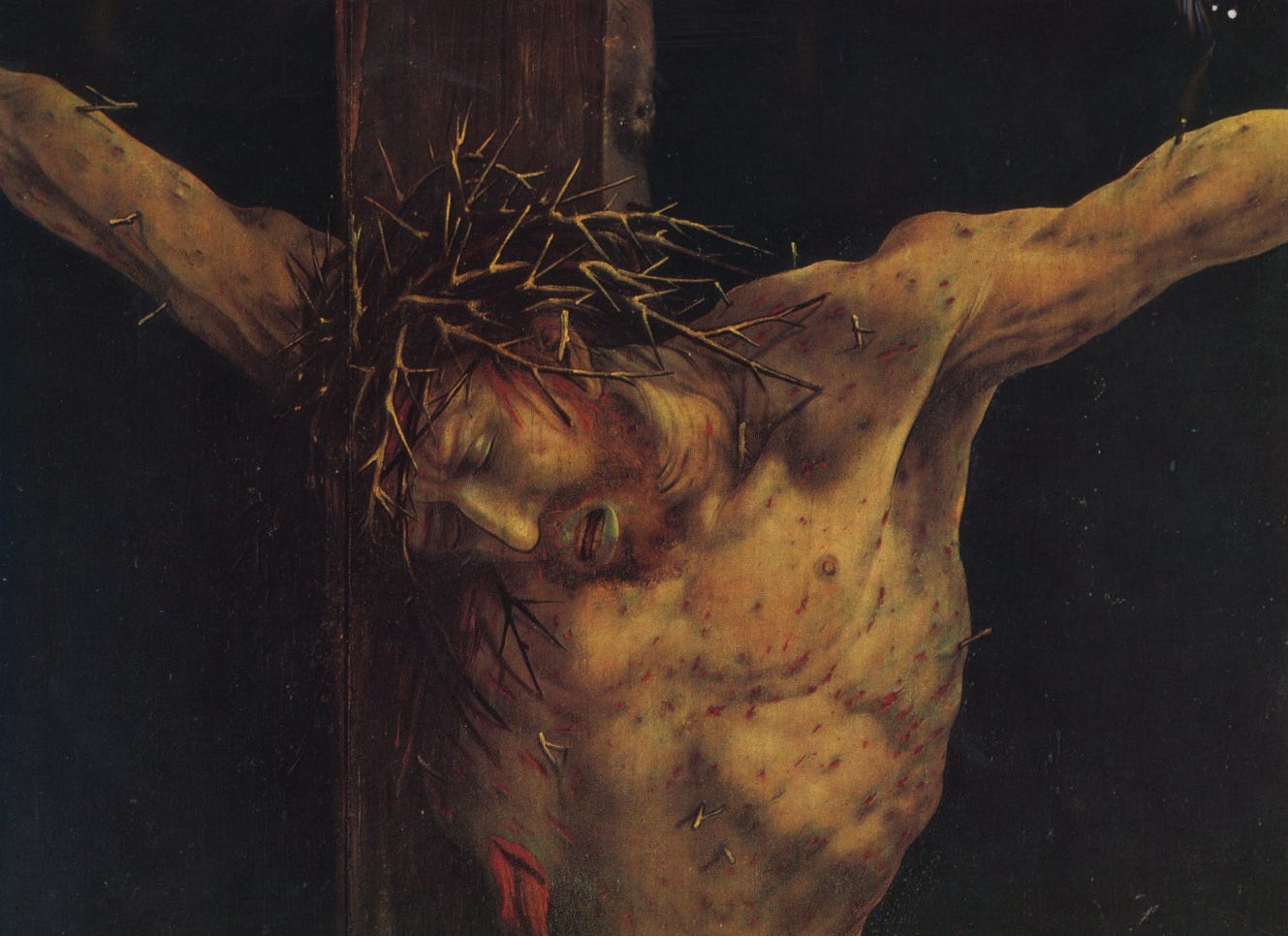

After his release, Barabbas, a stocky man with deep-set eyes and a large scar slashing his face (acquired in a knife fight with his own father), surreptitiously follows Jesus to Golgotha. Although he’s heard stories about this odd man’s power, he can scarcely credit them as he stares at the dying Jesus.

“There was nothing vigorous about the fellow. His body was lean and spindly, the arms slender as though they had never been put to any use. A queer man. The beard was sparse and the chest quite hairless, like a boy’s. He did not like him […] If anyone looked powerless, he did. Surely no one could look more wretched hanging on a cross. The other two didn’t look a bit like that and didn’t seem to be suffering as much as he. They obviously had more strength left. He hadn’t even the strength to hold his head up; it had flopped right down.”7

Barabbas, the hardened brigand who’s done his fair share of robbery, rape, and murder, thinks of power in terms of brute physical strength. How can a 97-pound weakling like Jesus possibly possess power? He seems a genuine loser, a nobody. Bizarrely, however, the man’s followers claim him to be the Son of God who willingly dies “in our stead. Suffered and died, innocent, in our stead.”8 Barabbas can’t make heads or tails of this. God has a son? Who sacrificed himself for humans? Absurd!

Still, Barabbas can’t help feeling that there’s something to this crucified man, even though he can’t put his finger on it. Besides, the testimony of those who knew him insist that he did exert power, although not the kind Barabbas recognizes. “A remarkable power,” they claim. “He would merely say to one: follow me, and one had to follow. There was nothing else to be done. Such was his power. If you had known him you would have experienced it.”9 Whatever the power was that this strange man exerted, Barabbas admits that it’s drawn him in too.

“They [his followers] spoke of his having died for them. That might be. But he really had died for Barabbas, no one could deny it! In actual fact, he was closer to him than they were, closer than anyone else, was bound up with him in quite another way. […] He was chosen, one might say.”10

Haunted by this sensed connection to the crucified man, wanting—needing—to fathom the secret of his power, Barabbas begins to seek out and question his followers. They willingly share accounts of Jesus’ deeds, but he finds them implausible. Discovering that a woman with a cleft palate whom a few years earlier he seduced, impregnated, and then (typically) discarded has become a Jesus-follower, he goes to her for an answer. In what does this man’s power consist? “She stood for a moment looking down on the ground; then, giving him a shy look, she said in her slurring voice: —Love one another.”11

Barabbas is dumbfounded. He’s a man who has led “an active, dangerous life”12 entirely without love, never seeing what good it did anyone. So far as he’s concerned, love is a weakness that turns people into easy marks. But the crucified man’s uncanny hold on him, as well as the radiance that illuminated the woman’s face when she spoke about love, forces him to question his own understanding of power as brute physical force.

Barabbas, for the first time in his hitherto one-dimensional life, becomes aware of the in-betweenness of the human condition. On the one hand, there’s the clenched-fist power of merciless force; on the other, the open-armed power of love. The first for Barabbas is the habit of a lifetime; the second, an intriguing but discombobulating possibility. One belongs to the material, finite realm in which he’s comfortable; the other to the infinite, spiritual one which baffles him.

The rest of the novel traces Barabbas’ back-and-forth struggle between the two, wanting to believe the Jesus story and the power of love but not being able to. He feels himself drawn by it—the bond between him and the crucified man—but he simply doesn’t understand what it means and so ultimately can’t believe.

Years later, Barabbas once again runs foul of the law and this time is condemned for the rest of his life to slave labor. He’s paired by the authorities with a fellow prisoner named Sahak, who happens to be a Jesus-follower. Like all slaves, Barabbas and Sahak wear disks around their necks that identify them as human property belonging to the Roman state. But on the back of his disk, in a quiet gesture of defiance, Sahak has scratched ‘Christos Iesus.’ His real Master is the crucified man, not Rome.

Attracted by Sahak’s piety, Barabbas once again feels drawn to the crucified man’s peculiar power of love. He longs to participate in it to such an extent that he actually tells an eagerly listening Sahak that he witnessed the Resurrection. He isn’t lying so much as trying to convince himself that he really believes Jesus was powerful enough to rise from the dead. Perhaps pretending to believe will make it so. The self-deception lasts for a while; Barabbas even gets Sahak to carve the holy name on the back of his own disk. But in the long run, he can’t force himself to believe, and when Sahak’s allegiance to the God of love rather than the Caesar of armed power is discovered by the authorities, Barabbas, knowing that crucifixion awaits Jesus-followers, denies under questioning that he’s one of them.

“—And you? Do you also believe in this loving god?

Barabbas made no reply.

—Tell me. Do you?

Barabbas shook his head.

—You don’t? Why do you bear his name on your disk then?

Barabbas was silent as before.

—Is he not your god? Isn’t that what the inscription means?

—I have no god, Barabbas answered at last, so softly that it could hardly be heard.”13

When Barabbas goes on to confess that he wants to believe but can’t, the Roman official, in a crushing gesture of contempt, “drew out his dagger and scratched the point of it across the words ‘Christos Iesus.’ —There’s really no need, as you don’t believe in him in any case, he said.”14

For the rest of his life, Barabbas is haunted by the look of shocked betrayal on Sahak’s face as he’s hauled off to his death. Lying in the darkness of his prison cell, night after night, Barabbas “felt the crossed-out ‘Christos Iesus’ burn like fire against his heaving chest.”15 It becomes the emblem of his perpetual exile and unfailing loneliness. Even his connection with the crucified man now seems severed. “He was not bound together with anyone. Not with anyone at all in the whole world.”16

Taken to the city of Rome by his master, Barabbas one night hears cries of “Fire! Fire!” from the street. Rushing outside, he hears people shouting that the Christians are setting the city on fire. In fact, the accusers are imperial agents provocateurs, charged with blaming Jesus-followers for the fire Nero himself has ordered. But Barabbas doesn’t know this. He instantly concludes that the Christians are burning Rome down in the name of Jesus, and this immediately liberates him from the in-between tension of wanting to believe in Jesus but not being able to. That’s because the crucified man is now speaking Barabbas’ language, the language of destructive power and brute force, not the dulcet tones of namby-pamby love. Now, at last, he can believe! Finally the bond is re-established once and for all!

“The Savior had come!

The crucified man had returned, he of Golgotha had returned. To save mankind, to destroy this world, as he had promised. To annihilate it, let it go up in flames, as he had promised! Now he was really showing his might. And he, Barabbas, was to help him! Barabbas the reprobate, his reprobate brother from Golgotha, would not fail. Not now. Not this time.”17

Barabbas, filled with what he takes to be a Jesus-pleasing zeal, begins hurling fire brands into homes and shops. “It was spreading, spreading! Everything was one vast sea of fire. The whole world, the whole world was ablaze! Behold, his kingdom is here! Behold, his kingdom is here!”18

But, alas. The crucified man’s Kingdom is based on the fire of love rather than the flames of destruction, as Barabbas, once again to his befuddlement, is soon reminded. Ironically, almost as if the God he can’t believe in is playing a final practical joke on him, he’s rounded up with the totally innocent Christians, thrown into prison, and sentenced to die with them—as an accused Christian. There, he re-meets Peter, likewise arrested, but keeps his distance from him and the rest of the condemned disciples. He’s wary of them and they’re suspicious of him. But Peter gently rebukes them with words that clearly voice Lagerkvist’s own verdict on people who want to believe but cannot.

“We have no right to condemn him. We ourselves are full of faults and shortcomings, and it is no credit to us that the Lord has taken pity on us notwithstanding. We have no right to condemn a person because he has no god.”19

Barabbas goes to the cross—a long deferred execution, stretching all the way back to Golgotha—believing that his life has been meaningless.

“When he felt death approaching, that which he had always been so afraid of, he said out into the darkness, as though he were speaking to it:

—To thee I deliver my soul.

And then he gave up the ghost.”20

Saint Barabbas?

The ending of Lagerkvist’s novel is notoriously ambiguous. Does Barabbas come to believe in the final moments of his life? Is the “Thee” to whom he gives us his soul the crucified man-God? Or is it the darkness? I suspect the latter. As Simone Weil observed, some people will find metaxú a barrier rather than a corridor to the infinite and remain forever stuck in the in-between. Barabbas is one of them, a case study of someone who wants desperately to believe in love, in God, in salvation, but finds that option closed to him. We must conclude, then, that he died, as he lived, in darkness. But we may also hope that the final darkness into which he entered was that corridor to infinity denied him in life.

I would’ve been disappointed had Barabbas “come to Jesus” at novel’s end. His in-between struggle is too important a parable about the fate of those who yearn but fail to believe to be sugarcoated with a happy ending. His story, bleak though it is, offers comfort, or at least fellow-feeling, to the rest of us who oscillate back and forth in the metaxú, one day exulting in a sense of the transcendent and the next despondently doubting its very existence. The genius of Lagerkvist’s tale about Barabbas’ fate is that it helps us better understand our own situation—or, if it doesn’t describe us, prods us towards compassion for those it does. As Peter tells his fellow Christians, “We have no right to condemn a person because he has no god.” Quite the contrary.

Towards the end of his astounding play Amadeus, Peter Shaffer has the aged and bitter Salieri, forced by the example of Mozart’s genius to acknowledge himself a mediocre composer, turn to the audience with this chilling benediction:

“When you feel the dreadful bite of your failures—and hear the taunting of unachievable, uncaring God—I will whisper my name to you: ‘Salieri: Patron Saint of Mediocrities!’ And in the depth of your downcastness you can pray to me.”21

Barabbas: Patron Saint of Those Who Long to Believe in God But Can’t, Those Who Are Trapped in Metaxú, Those Who Shudder at the Icy Indifference of an Empty Universe, Those Who Find No Way Through: pray for us.

###

Pär Lagerkvist, Barabbas, trans. Alan Blair (New York: Vintage International, 1989), p. 116.

Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. Arthur Wills (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952), p. 200.

To his credit, I suppose, William James tried to circle the square in his “The Will to Believe” essay. But his treatment there of religious sensibility is exceeded in shallowness only by his equally overrated Varieties of Religious Experience.

Voegelin explores metaxú in much of his writing. Two accessible introductions (Voegelin is a notoriously difficult thinker and awkward author) are a couple of his essays: “Structures of Consciousness” in The Drama of Humanity and Other Miscellaneous Papers 1939-1985, ed. William Petropulos and Gilbert Weiss (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), pp. 351-383, and “The Gospel and Culture” in The Eric Voegelin Reader, ed. Charles R Embry and Glenn Hughes (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2017), pp. 245-286. The passage from the Symposium that inspired Voegelin is where Diotima, describing Eros as a mighty “daimon” or power, says that “the whole of the daimonic is between [metaxú] god and mortal” (202d13-e1). Plato probably intends metaxú here as a simple preposition, but Voegelin transforms it into a substantive noun to describe an actually existing liminal space. This interpretation is the hub of much Voegelin criticism.

See especially Chapter 1 of Taylor’s A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007), pp. 25-89.

Matthew 27:15-26, Mark 15:6-15, Luke 23:18-25, and John 18:39-40. Matthew calls him “Jesus Barabbas,” which makes the fictional link between Jesus and Barabbas in Lagerkvist’s novel even more interesting.

Lagerkvist, Barabbas, pp. 4-5, 7.

Ibid., p. 26.

Ibid., p. 27.

Ibid., pp. 46, 47.

Ibid., p. 41

Ibid., p. 43.

Ibid., pp. 115-116.

Ibid., 118.

Ibid., p. 127

Ibid.

Ibid., pp. 134-135.

Ibid., p. 135.

Ibid., pp. 142-143.

Ibid., p. 144.

Peter Shaffer, Amadeus (New York: Harper & Row, 1981), p. 95.