Now Christmas is come, Let us beat up the drum, And call all our neighbors together; And when they appear, Let us make such a cheer, As will keep out the wind and the weather!1

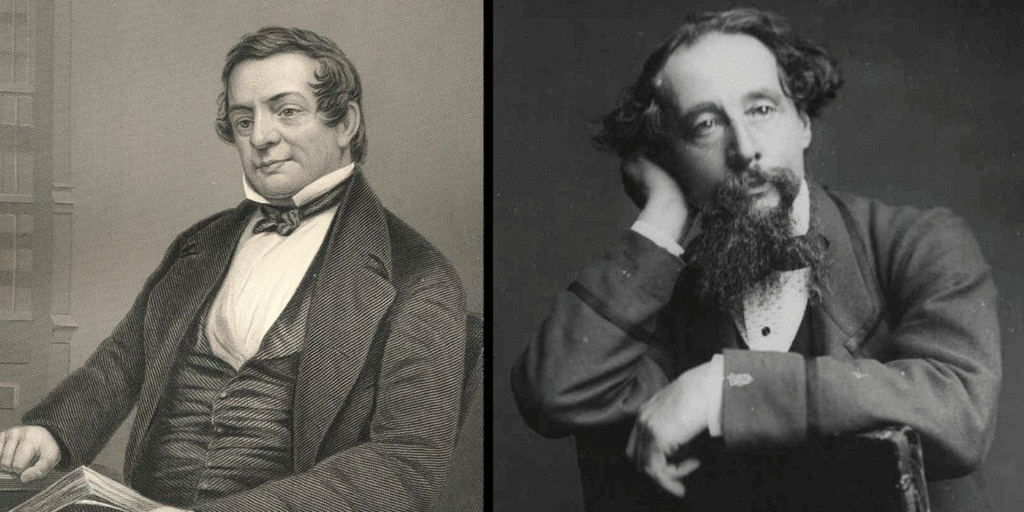

In January 1842, the American author of the Halloween story wined and dined the British author who, the following year, would write the Christmas story.

The two became acquainted when the young Charles Dickens arrived at New York harbor on his first literary tour of the United States. He was greeted by hundreds of cheering, adoring fans, wild to meet the author of Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, and Nicholas Nickleby. Washington Irving, the reigning doyen of American letters, was on the dock to welcome Dickens. Admirers of one another’s work, they were delighted to meet.

Everyone’s familiar with Irving’s spooky Halloween tale about the Headless Horseman’s revenge and Dickens’ heartwarming Christmas one about Ebenezer Scrooge’s redemption. But what isn’t so well known is that Irving wrote a series of Christmas tales nearly a quarter-century before A Christmas Carol appeared. Dickens read and enjoyed them, and surely had them in mind when he came to write his own Yuletide fable.

I bow to no one in my love of Dickens’ story. Every time I reread it—and I do so every Christmas—it fills me with a happy glow. At the same time, I also love Irving’s Christmas tales, set at the fictional Bracebridge Hall in Yorkshire. They awaken in me that same wonderfully seasonal mixture of festive gaiety and fireside coziness that Dickens’ Carol does. Perhaps they will in you too.

Knickerbocker’s Santa Claus

The five interlocking Bracebridge Hall stories—“Christmas,” “The Stage-Coach,” “Christmas Eve,” “Christmas Day,” and “The Christmas Dinner”—weren’t Irving’s first imaginative dive into Yuletide. In his 1809 parody A History of New York, presumably the work of a crochety bachelor named Dietrich Knickerbocker, Irving conjures a vision of St. Nicholas—or, in Dutch, Santa Claus—who magically designates with the smoke from his pipe where Dutch immigrants to the New World are to settle.

“And lo! the good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children. And he descended …. and he lit his pipe by the fire, and sat himself down and smoked; and as he smoked the smoke from his pipe ascended into the air, and spread like a cloud overhead. And …. the smoke spread over a great extent of country …. assum[ing] a variety of marvelous forms, where in dim obscurity shadowed out palaces and domes and lofty spires, all of which lasted but a moment, and then faded away, until the whole rolled off, and nothing but the green woods were left.”2

The History was an instant success, catapulting Irving into national literary prominence. It also re-introduced St. Nicholas or Santa Claus to a culture whose Puritan heritage had all but banished Christmas from the calendar as a frivolous (not to mention papist!) holiday.

At the Bracebridge Christmas Revels

Six years later, hoping to salvage his family’s floundering business interests, Irving traveled to England to assist his entrepreneurial brother. He remained abroad for nearly twenty years, failing to rescue the family fortune but writing The Sketch-Book, his finest fictional work. It’s a collection of short stories or “sketches” which includes the famous “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle” as well as the nearly forgotten Christmas stories.3

The narrator of the stories is Geoffrey Crayon, Irving’s “gentleman” alter ego. An American touring Britain, he’s invited to Bracebridge Hall for the holiday. The five stories’ timeline begins on Christmas Eve, with Crayon traveling in a stagecoach, and ends with Christmas night festivities at the Hall. Along the way, Irving introduces us to an assortment of characters who may be a bit ridiculous but are also kind-hearted and generous in the best Christmas spirit. Their very eccentricities make them all the more lovable.

Three of them in particular stand out.

There’s the master of Bracebridge Hall, called “the Squire” by everyone, including his own grown children, “a tolerable specimen of what you will rarely meet with now-a-days in its purity—the old English country gentleman.”4 He’s a lover of tradition, no matter how threadbare or arcane it may seem.

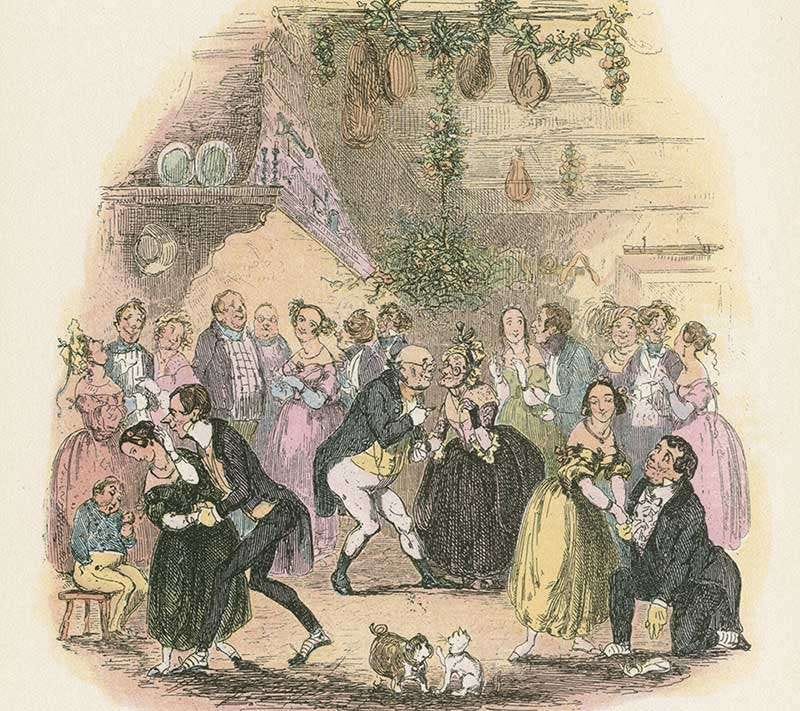

The Squire encourages good-natured revelry in his household throughout the twelve days of Christmas. The great hall of his manor is festooned with holly and mistletoe (according to custom, for every kiss, a mistletoe berry must be removed from the sprig; once they’re all gone, no more kisses are allowed). Under the seasonal greenery, much laughter, dancing, and innocent tomfoolery take place until “the old manor house almost reeled with mirth.”5 Old carols are sung, wassail, frumenty, and a delicious assortment of other drink and food are enjoyed, and children run around squealing with excitement and delight. With the Squire’s gleeful encouragement, there’s “complete abandonment to mirth and good fellowship [which] throws open every door, unlocks every heart.”6

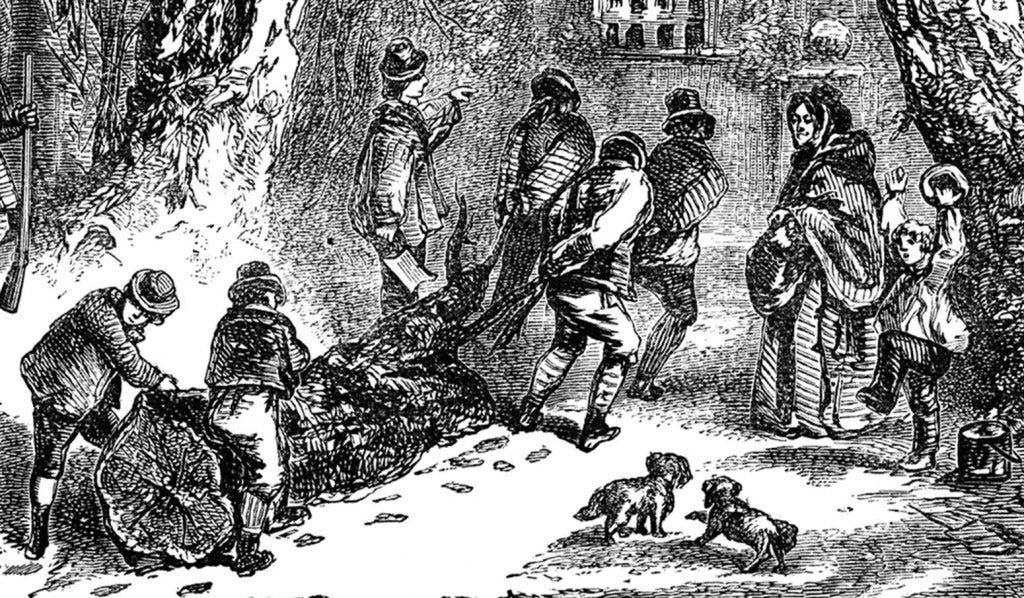

The Squire especially rejoices in the “yule clog” (yes, clog, not log), an enormous tree root lit with great ceremony on Christmas Eve by a brand from the previous year’s yule clog. It’s intended to burn all night in the great hall’s fireplace until only enough is left to light the next year’s Christmas fire.

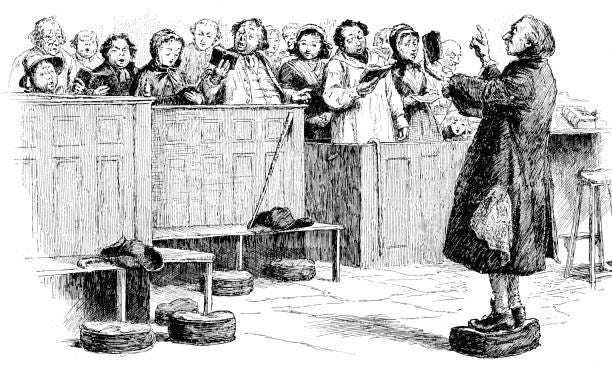

Then there’s Master Simon, an aged hanger-oner and cousin to the Squire, “a tight brisk little man, with the air of an arrant old bachelor”7 who enthusiastically serves as the self-appointed Master of Revels. He’s a shameless flirt with all the young ladies and a perennial organizer and participant in holiday games. A music fancier, he recruits some of the local talent as chapel choristers on Christmas morning. Things go wonderfully awry, although no one seems to mind.

“Unluckily there was a blunder at the very outset—the musicians became flurried; Master Simon was in a fever; everything went on lamely and irregularly, until they came to a chorus beginning ‘Now let us sing with one accord,’ which seemed to be a signal for parting company: all became discord and confusion; each shifted for himself, and got to the end as well, or, rather, as soon as he could; excepting one old chorister, in a pair of horn spectacles, bestriding and pinching a long sonorous nose; who, happening to stand a little apart, and being wrapped up in his own melody, kept on a quavering course, wriggling his head, ogling his book, and winding all up by a nasal solo of at least three bars’ duration.”8

And speaking of chapel, there’s also the local parish priest, an unimaginative bookworm with an “adust temperament” who zealously “followed up any track of study, merely because it is denominated learning.”9 His Christmas Day sermon is a never-ending monotoned rundown of all the Church Fathers who argued that the Nativity was properly an occasion for rejoicing. “I was a little at a loss,” observes a bemused Crayon, “to perceive the necessity of such a mighty array of forces to maintain a point which no one present seemed inclined to dispute.”10 Later, at the Christmas dinner in the great hall, the priest, who by this time has imbibed a bit too much wassail, shakily rises to deliver a learned lecture on Christmas carols to the assembled revelers.

“[He addressed] himself at first to the company at large; but finding their attention gradually diverted to other talk, and other objects, he lowered his tone as his number of auditors diminished, until he concluded his remarks in an under voice, to a fat-headed old gentleman next him, who was silently engaged in the discussion of a huge plateful of turkey.”11

Christmas Glow

Under different circumstances, these three characters might come across as insufferable: the Squire as an old man stuck in the past, Master Simon as an embarrassing moocher, and the priest as a dry-as-dust pedant. But they’re portrayed with a generous warmth that’s perfectly in keeping with “the season of regenerated feeling—the season for kindling not merely the fire of hospitality in the hall, but the genial flame of charity in the heart.”12 Irving’s affection for them is so infectious that we readers wind up genuinely liking them. Seen through the cheery glow of Christmas, their eccentricities are more touchingly amusing than annoying. The lesson is obvious: we should consider the eccentricities of our own friends and relatives with the same generosity, at all times but especially at Christmas.

This is only as it should be, because Christmas is a time which asks that we open our homes and hearts to all and sundry. It is, says Irving, “the season for gathering together of family connections, and drawing closer again those bands of kindred hearts, which the cares and pleasures and sorrows of the world are continually operating to cast loose.”13 To come out of winter bleakness into a room warmed by a blazing hearth, the company of loved ones, and merry laughter is a restorative tonic. “Heart calleth unto heart, and we draw our pleasures from the deep wells of living kindness which lie in the quiet recesses of our bosoms.”14

Each family has its own Christmas traditions and memories. But the golden thread that connects them all is their shared joy. That’s exactly what Crayon encountered when he celebrated Yuletide at Bracebridge Hall. He learned there that “surely happiness is reflective, like the light of heaven; and every countenance bright with smiles, and glowing with innocent enjoyment, is a mirror transmitting to others the rays of a supreme and ever-shining benevolence.”15 What better gift could a celebration of the Nativity of the Prince of Peace offer?

That’s the gift Washington Irving and I wish for everyone this joyful, wondrous season. Happy, happy Christmas!

###

Washington Irving, “Christmas Eve.” The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (New York: New York: A.L. Burt, n.d.), p. 185.

Washington Irving, Knickerbocker’s History of New York, Volume 1. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1894), pp. 181-183.

I can’t resist mentioning one of my favorite pieces in the collection, “The Mutability of Literature,” in which a small quarto volume tells the narrator how terrible it is to be a forgotten and dusty book hidden away on a shelf. It’s a melancholy little tale, made all the more so by the fact that it portends Irving’s own slippage into obscurity. He deserves better than he’s received.

Irving, “Christmas Eve,” The Sketch-Book, p. 178.

Irving, “The Christmas Dinner,” The Sketch-Book, p. 214.

Irving, “Christmas,” The Sketch-Book, p. 167. The Squire very much reminds me of old Fizziwig in Dickens’ Christmas Carol.

Irving, “Christmas Eve,” p. 184.

Irving, “Christmas Day,” The Sketch-Book, p. 196.

Ibid., p. 194.

Ibid., p. 197.

Irving, “Christmas Dinner,” The Sketch-Book, p. 205.

Irving, “Christmas,” The Sketch-Book, p. 169.

Ibid., p. 166.

Ibid., p. 167.

Ibid., pp. 169-170.

Among other things, in your deft highlighting of Washington Irving’s inimitable tales, you tacitly remind us of our rich English belles lettres traditions. Alas, these traditions are generally ignored in our own “democratized” internet age, an age of largely tone-deaf “story telling” drivel.