Isaac, the son of Abraham, suffered a trauma from which he never quite recovered and which he passed on to his own son Jacob.1 I’m referring, of course, to the Akedah, the “binding of Isaac,” that dreadful moment in Genesis when, supposedly in obedience to a divine command, Abraham raised a knife to sacrificially cut Isaac’s throat.

It’s no exaggeration to say that this story has haunted the western imagination for centuries, leaving rabbis, Church Fathers, literary and visual artists, philosophers (most famously, probably, Kierkegaard2), and ordinary believers struggling to make sense of it. What kind of a God would command a father to kill his beloved son? And why would a father obey such a cruel and seemingly senseless order?

But what if the questions and the moral bafflement that births them are based on a misreading of the story? A case can be made that God in fact doesn’t command Abraham to sacrifice Isaac. Coming to this conclusion invites an interpretation of the Akedah that eliminates, or at least softens, the bewilderment and outrage that the tale’s conventional interpretation evokes.

The Request-Blessing Pattern

The alternative interpretation revolves around the Hebrew predicate nā' / נא. In English Bibles, נא usually is either left untranslated or rendered as “now” or “then.” But its primary meaning is “please” or “pray,” as in “Please do x” or “I pray you to do x.” It expresses a request.

So, for example:

“The LORD said to Abram, after Lot had separated from him, ‘Lift up your eyes, and look from the place where you are, northward and southward and eastward and westward; for all the land which you see I will give to you and to your descendants for ever.’” (Gen 13:14-15, RSV) Literally, the passage begins with nā': “Please (or pray) lift up your eyes…”

or

“And God brought Abraham outside and said, ‘Look toward heaven, and number the stars, if you are able to number them.’ Then he said to him, ‘So shall your descendants be.’”(Gen 15:5, RSV) Once again, the passage literally begins with nā': “Please (or pray) look toward heaven...”

or

“And God said [to Jacob], ‘Lift up your eyes and see, all the goats that leap upon the flock are striped, spotted, and mottled,’” and hence are Jacob’s. (Gen 31:12 RSV) What does God literally say here? You guessed it: “Nā' lift up your eyes…”

All three of these passages display the same request-blessing pattern: God asks the recipients to do something that enables them to recognize a gift or blessing God wishes to bestow. If you’ll please lift up your eyes, Abraham, you’ll see all the land I plan to bless you with. If you’ll please gaze at the stars, you’ll see how many descendants I’m going to give you. If you’ll please take a look, Jacob, you’ll see all the herd-wealth I’m awarding you.

Note that the request-blessing pattern isn’t transactional. There’s no quid pro quo going on here. God isn’t expecting something in return. Instead, God simply invites notice of the blessings he bestows so that the hearts of the recepients may be strengthened and gladdened.

The Akedah Request-Blessing

At the beginning of the Akedah story, standard English interpretations have God saying this to Abraham:

“‘Abraham! […] Take your son, your only son Isaac,3 whom you love, and go to the land of Mori’ah, and offer him there as a burnt offering upon one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.’” (Gen 22:1,2 RSV)

Rendered this way, God’s words really do come across in the imperative tense, don’t they? But the problem is that the נא is silenced here, just as it is in the three other request-blessing passages. The Akedah’s literal beginning is “nā' qaḥ-” (נָ֣א קַח־): “Please take…”45

Moreover, the request-as-prequel-to-blessing pattern found in other nā' passages is also repeated.

“Because you have not withheld your son, your only son, I will indeed bless you, and I will multiply your descendants as the stars of heaven and as the sand which is on the seashore. And your descendants shall possess the gate of their enemies, and by your descendants shall all the nations of the earth bless themselves because you have obeyed6 my voice.” (Gen 22:16-18 RSV)

Again, this isn’t a transaction.7 Lifting up one’s eyes in the earlier nā' passages is a necessary condition for recognizing the blessing the LORD has already bestowed. The act of not withholding Isaac serves the same purpose here. It involves a transition from conventional ways of seeing and knowing to alternative and spiritually insightful ones: a teshuvah/metanoia. In the earlier passages, the lifting of eyes symbolizes a renewed receptivity to the Divine. Similarly, in the Akedah, not withholding Isaac symbolizes a letting-go of the self-will that opens Abraham up to God’s expansive blessing.

There’s no divine command here, only a divine invitation—nā'—to receive.

Is It a Difference That Makes No Difference?

A this point, it’s fair to ask: so what? Isn’t a request for Abraham to slay his son just as vile as a command to do so? Isn’t all this nā' business just wordplay, a difference that make no difference at all?

I don’t think so, for three reasons.

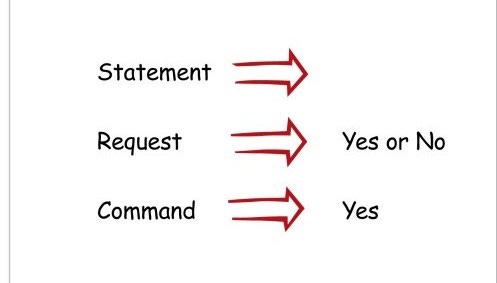

(1) The issuance and reception of a command just isn’t the same as the issue and reception of a request. There’s an obvious difference in intent, tone, and response.

Orders imply a relationship based on power differentials: the person who orders is superior and the person ordered is subordinate. The former can command whatever he wishes. He’s unfettered. The latter’s freedom is constrained. He has but two choices: obey—say “yes”—or face unpleasant consequences.

Requests imply a less lopsided relationship in which the asker acknowledges the recipient’s right to freely comply or refuse. A degree of mutual respect and trust is implied. Refusal of a request may create a temporary awkwardness but doesn’t carry the threat of retribution that disobedience to a command does.8

God’s nā' means that He’s not coercing Abraham, hamstringing his freedom, or threatening dire consequences should Abraham refuse. If anything, the implication is that a refusal will sadden God because it means that Abraham neither recognizes nor embraces the blessing.

(2) Moreover, everything we’re told about God in Genesis runs counter to accepting that He actually would order a loving father to kill his son. Time and again, God’s merciful steadfastness is displayed in his dealings with mortals, and particularly with Abraham’s clan. The Akedah, if interpreted as a command, is an episode that just doesn’t fit with the portrait of God we’ve been given. Moreover, it implies that God is willing to break His word. He promised that Isaac—this son, not some other—would be the inheritor of the vow made to Abraham. “It is with Isaac that I will maintain my covenant as an everlasting covenant and with his descendants after him.” (Gen 17:19) It’s unthinkable that God would rupture the covenant, which is exactly what ordering the death of Isaac would do.

(3) If we interpret the Akedah as a command, God’s “test” of Abraham seems cruelly harsh. But if we read it as God making a request, the upshot is something like this. “I’m asking you, Abraham,” says God, “if you’re willing to choose me above everything and anyone else. Once you make that interior commitment”—the leap of faith, as Kierkegaard would say—“you’ll see the world and everything in it—including yourself and your loved ones—in an entirely different light. You’ll finally comprehend the power of the blessing—all that jazz about stars and sand and nations—I’ve already bestowed upon you. And in doing so, you’ll have a better idea of who you are and who I am.”

This both fits in with the request-blessing pattern as well as the point about textual consistency in describing God’s nature. Perhaps Abraham trudged up Mount Moriah and held the knife over Isaac, ready to strike, because he misunderstood. Perhaps he thought that God was looking for a literal sacrifice of Isaac instead of a spiritual teshuvah/metanoia on his part. We humans seem perennially and tragically to prefer external to internal actions. But Abraham’s (and our) confusion about what God said is one thing, and God’s actual intention another.

So there it is: my attempt to argue that because God didn’t command Abraham to kill Isaac, the troubling moral and theological questions such an order raises are moot. Am I fully satisfied with this alternative reading of the Akedah story? In all honesty, no. But I do find it preferable to the conventional interpretation.

And so, nā', may you.

###

Isaac’s trauma is the topic of the forthcoming first part of my series “Jacob the Wayfarer.”

Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling (1843) is an exercise in plumbing the dread he imagines Abraham experiencing upon receiving the divine command. Kierkegaard’s analysis is interesting; but his constitutional inability to self-edit his cascades of prose is annoying.

Of course Isaac isn’t Abraham’s only son; there’s also Ismael, the son of the slave woman Hagar. But Isaac is the putative inheritor of God’s covenantal promise to Abraham. He is his “only” legitimate son/heir.

I’m indebted here to Robert D. Sacks’ analysis in his brilliant but sadly underappreciated The Lion and the Ass: Reading Genesis After Babylon (Sante Fe, NM: Kafir Yaroq Books, 2019), pp. 183-185

To the best of my knowledge, the only translation of Genesis 22:2 that acknowledges the nā' is Robert Alter’s translation of the Hebrew Bible. Volume 1, The Five Books of Moses (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019), p. 72.

The Hebrew word translated here as “obeyed” is a form of the verb shama`(שָׁמַע), which means “to listen, hear, or obey.” If one reads what God says to Abraham as a command, then obviously the appropriate translation is “obey.” But if what God says to Abraham is a request, then “listen” or “hear” is more appropriate.

It may appear transactional because of the RSV translation of kiy / כִּי as “because.” But kiy also means “indeed” or “surely.” When rendered this way, the transactional connotation suggested by “because” disappears.

A simple illustration of the difference in tone, relationship, and response between ordering and requesting: “Take out the garbage now!” vs “Please take ought the garbage now?”

Hello there :) Can you tell me: what is the Hebrew word for the "please(d)" in this verse: Isaiah 53:10 -- "It pleased the Lord to bruise him"

Your interesting words here brought this verse to my mind, and I began to wonder about the Christ. Given that the Son and the Father are One, and the Father was pleased to bruise the Son, what pleased the Father would please the Son and the pleasure of the Son would, thereby, please the father.

Given all of this, can we allow for the posture of the Son to be "Father, nā' bruise Me"? And if we can do that, do we begin to see Abraham and Isaac's interaction as an imperfect foreshadowing of the perfect Father/Son interaction that was to come?

Thank you for your beingness in this world.