Don't "Read" Mark's Gospel

Instead, listen to it!

Whenever you or I have something terribly exciting or urgent to tell, we frequently mangle grammatical tenses in our rush to get the words out, don’t we?

Here’s an example.

“So, I was at the bus stop, minding my own business, and suddenly I see this guy on the corner, just a few feet away from me. He staggered and collapsed. And I run over to him and I said, ‘What’s going on, buddy? Are you okay?’ and he says to me, ‘I think I may be dying.’ And so I whipped out my phone and call 911 and stay with him until the ambulance arrived. Naturally I miss my bus. And when I got home that night, the first thing I say to my wife was ‘You won’t believe what happened to me today!’”

This is a perfectly natural way of telling a story, and only a grammar prude would object to its tense-mixing. In fact, the mixing adds a vibrant you-are-there quality to the tale that keeps us on the edge of our seat. It conveys a slightly breathless, sprint-like feel, and that’s what captures and holds our attention when we listen to it.

This is precisely what Mark’s Gospel does. It has a vibe of urgency that immediately gives the impression that a wide-eyed Mark, quivering with excitement, absolutely needs to tell us something so important that he rushes to get it out before he forgets any of it. He chops the air with a lot of excited hand gestures, sputters at times, impatiently strings together run-on sentences, occasionally gets confused about the sequence of events—but never mind, rush on!—and doesn’t bother pausing to align his tenses.

In short, Mark’s telling a story in exactly the same way any thrilled person would, the words and sentences just gushing out of him. To genuinely appreciate what he says we really need to hear it in all its vividly excited tones rather than read it cold off a page of type.

I don’t think this can be said about the other Gospels. Parts of them, notably Jesus’s parables, likewise ought to be listened to instead of silently read. But for the most part, Matthew’s, Luke’s, and John’s Gospels are intended for readers, not hearers, despite the fact that they were transmitted orally before being written down.

Mark’s Gospel, from first to last, is meant to be heard, or at least is best appreciated when listened to rather than read silently.

Why do I say this?

In the first place, it’s the briefest of the four gospels, tailor-made to be heard in one sitting. We’re able to swallow it in one gulp, as should be the case whenever we’re told a story.

Second, it’s short because it’s so fast-paced. One of the ways Mark speeds things up is his frequent use of εὐθύς / euthys, “immediately” or “right away.” He loves the word, employing it forty-two times, often to make transitions between events. By way of comparison, the more stolid Matthew uses it seven times and Luke but once.

Third, Mark strings together his sentences in a breathlessly urgent way. There are some eighty-eight sections or pericopes in his gospel. A full eighty of them are prefaced by καί / kai, “and.” This technique is called parataxis, and when Matthew and Luke lift sections of Mark’s gospel to include in theirs, they typically edit most of his “ands” out, presumably because they disdain them as peculiarities of street talk—which of course they totally are.

Finally, as I’ve already suggested, Mark isn’t worried about coordinating his use of tenses. He wants to capture our attention with a what-happens-next!? nailbiter of a story, and lets the words flow as they naturally would coming from an excited speaker. Again, Matthew and Luke fancy themselves too sophisticated for this, and so regularly clean up Mark’s grammar when they appropriate passages from him.

Unfortunately, so do most English translations of Mark. Apparently all his “immediatelys” and “ands” are often judged too undignified for a biblical text. So translators feel obliged to schoolmarm Mark’s gospel. Their red-penciling turns his Gospel into a document to be read rather than a story to be listened to.

Let me give you a couple of representative examples of how standard English translations “clean up” Mark. Here’s a rendering of Mark 1:9-13, from the New American Bible (Catholic):

It happened in those days that Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized in the Jordan by John. On coming up out of the water he saw the heavens being torn open and the Spirit, like a dove, descending upon him. And a voice came from the heavens, “You are my beloved Son; with you I am well pleased.” At once the Spirit drove him out into the desert, and he remained in the desert for forty days, tempted by Satan. He was among wild beasts, and the angels ministered to him.

And here’s a less pristine (I’m almost tempted to say less prissy), more faithful rendering of the same passage from David Bentley Hart’s recent translation1 of the New Testament:

And in those days it happened that Jesus, from Nazareth of Galilee, came and was baptized in the Jordan by John. And, immediately rising up out of the water, he saw the heavens being rent apart and the Spirit descending to him as a dove. And a voice out of the heavens: “You are my Son, the beloved, in you I have delighted.” And immediately the Spirit cast him out into the wilderness. And he was in the wilderness forty days, being tempted by the Accuser, and was with the wild beasts, and the angels ministered to him.

Or how about these two versions of Mark 1:40-44? First, the New American Bible’s:

A leper came to him [Jesus] and kneeling down begged him and said, “If you wish, you can make me clean.” Moved with pity, he stretched out his hand, touched him, and said to him, “I do will it. Be made clean.” The leprosy left him immediately, and he was made clean. Then, warning him sternly, he dismissed him at once. Then he said to him, “See that you tell no one anything, but go, show yourself to the priest and offer for your cleansing what Moses prescribed; that will be proof for them.”

And now Hart’s:

And a leper comes to him, imploring him and falling to his knees, saying to him, “If you wish it, you are able to cleanse me.” And, moved inwardly with compassion, he stretched out his hand and touched him, and says to him, “I wish it, be clean.” And the leprosy immediately left him, and he was cleansed. And, sternly admonishing him, he immediately thrust him out, and says to him, “See that you tell nothing to anyone, but go show the priest and offer the things Moses commanded for your cleansing, for a tetimony to them.”

Do you sense the difference between the two? The ones from the New American Bible are definitely somewhat domesticated texts that invite a quiet, solitary, and rather sedate reading. But the more faithful Hart translations exude a sense of suspensefulness and urgency2 that begs to be heard rather than silently read—and heard, moreover, with companions. I imagine Mark telling us this story as we, friends all, gather around him in the evening. The kids have been put to bed, the supper dishes have been stacked, our wine glasses have been refilled, the lights have been turned down low. Mark leans in, fixes us with glittering eyes, and begins in a voice quivering with excitement: “I’ve been dying to tell you something all night! Listen to this!”

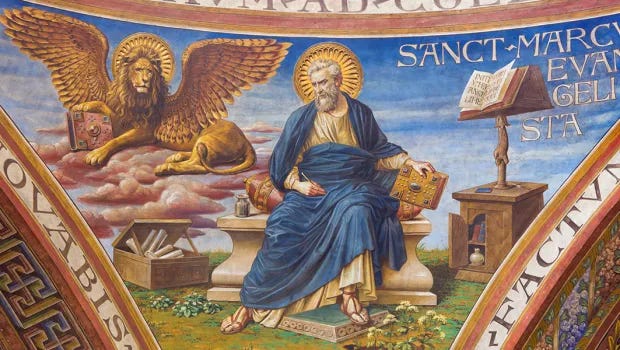

Each of the Gospels most likely started out as oral tradition, stories told first- and second-hand to small groups of people, first in Palestine, then Turkey and Greece, and then in Rome. But Mark’s most clearly carries the immediate feel of oral story-telling. Morever, we have historical confirmation that it’s pretty much a realtime transcription, rather than a continuously reworked and redacted edition, of Simon Peter’s public and private recollections. As the first-century Apostolic Father Papias tells us,

“Mark became Peter’s interpreter and wrote accurately all that he remembered, not, indeed, in order, of the things said or done by the Lord. For he had not heard the Lord, nor had he followed him, but later on, as I said, followed Peter, who used to give teaching as necessity demanded but not making, as it were, an arrangement of the Lord’s oracles, so that Mark did nothing wrong in thus writing down single points as he remembered them. For to one thing he gave attention, to leave out nothing of what he had heard and to make no false statements in them.”3

Given the circumstances of how it came together, there’s a certain sloppiness to Mark’s Gospel. But the sloppiness is part of the reason it sounds so utterly authentic when we hear it (and even when we read it, although I think the effect is much less dramatic).

Let me offer a final reason why it’s good to hear, and not just read, Mark. When a good story teller approaches the climax of her tale, she almost instinctively slows the pace as a way of signalling that something big is about to happen, thereby grabbing her listeners’ attention even more securely. Just remember the cadences of ghost stories when we were kids sitting around a campfire listening to them. As the tale’s moment of truth approaches—the killer’s hook discovered in the car’s doorknob!—the adroit story-teller began to speak more slowly (or, as we said back then, creepily), letting her words sink into us.

Something like this happens in Mark’s Gospel. His breakneck pace slows as he approaches the Passion, the climax of his story. Before that point in the tale, he gestures at time lapses in quick, almost impatient ways: “after several days” (2:1), for example, or “in those days” (8:1). But beginning in Chapter 11 with Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem, he starts to name specific days and times—even hours, when it comes to the final day of Jesus’s life—putting on the brakes to clue us in that what he’s about to tell us needs to be heeded. A sense of awe at what’s about to happen slows him and us down.

Many Christian denominations liturgically focus on the three synoptic Gospels on a rotating three-year cycle. This year, the one that began in Advent (1 December 2024), is devoted to Mark’s. So for church-goers, there’s ample opportunity to actually hear it. But here’s my recommendation for everyone, religious or not. Get hold of a copy of Hart’s translation, gather friends over a bottle of wine, turn off the cell phones, and take turns reading and listening to the story. I think you’ll find it a worthwhile aesthetic and—who knows?—perhaps spiritual experience. As literary critic Helen Gardner astutely points out,

“[Listening] to Mark’s Gospel is like [listening] to a poem. It is an imaginative experience. It presents us with a sequence of events and sayings which combine to create in our minds a single complex and power symbol, a pattern of meaning.”4

###

David Bentley Hart, The New Testament: A Translation (New Have, CT: Yale University Press, 2017). Like all translations, there are aspects of Hart’s that can and have been disputed. But his rendering of Mark’s Gospel is, in my estimation, spot-on.

In all honesty, I’d delete most of the commas Hart inserts after the “ands” to accentuate even more the breathless pace of Mark’s words.

Eusebius, The Ecclesiastical History, Volume 1. Trans. Kirsopp Lake (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1926), Book III, xxxix, p. 297. Eusebius also writes (Volume 2, Book VI, xiv, p. 49) that Clement of Alexandria likewise attests to the tradition:

“The Gospel according to Mark came into being in this manner: When Peter had publicly preached the word at Rome, and by the Spirit had proclaimed the Gospel, that those present, who were many, exhorted Mark, as one who had followed him for a long time and remembered what had been spoken, to make a record of what was said; and that he did this, and distributed the Gospel among those that asked him. And that when the matter came to Peter’s knowledge he neither strongly forbade it nor urged it forward.”

With apologies to Helen Gardner, I’ve substituted “listening” for “reading” here. I believe, however, that the thrust of her lovely essay “The Poetry of St. Mark,” from which this quote is taken, is really about hearing the Gospel. After all, that’s the appropriate mode of receptivity for poetry. Helen Gardner, The Business of Criticism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959), p. 103.

Meditate on Mark, using the Rosary

This is so beautiful.

There is nothing more stunning than the passionate stumbles of the lame man just healed, who is filled with a wild wonder and worship that outruns his newly-strengthened legs.

May we never lose our connection with the Sacred Romance to Whom we are wed,

as we cast with abandon

perfume-soaked caresses

upon burnished feet

of our Wilderness Lover.

Thank you for writing this.