“Boredom evokes an evil without any site, without any support, without anything except this nothing, unidentifiable, which erodes you.” —E.M. Cioran1

Yelena: “I’m dying of boredom, I don’t know what to do with myself.”—Anton Chekhov2

Strangely, I remember them well: those interminable Sunday afternoons of my childhood when uncles and aunts would gather at my grandparents’ house to drone on about their latest aches and pains or speculate about the coming week’s weather. These gatherings left me numb, empty, spent (which is why it’s strange that my memory of them is so vivid). A miasma of excruciating boredom engulfed me every time I sat through one of them. They were afternoons of the living dead, repeated every seven days.

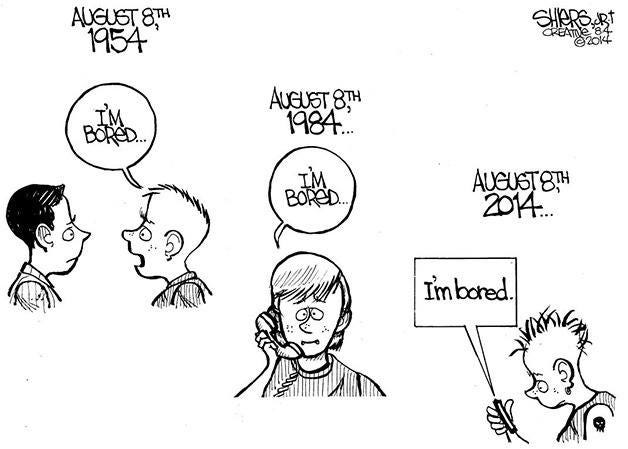

Boredom is a common enough experience, but one that’s proven surprisingly hard to define. There’s something fuzzy about it. Is it an emotion? A mood? An attitude? A nexus of several mental states? But most philosophers, psychologists, and sociologists3 who think about boredom agree that there are two basic kinds.

What I endured on those endless Sunday afternoons is “simple” or “situational” boredom.4 We’ve all felt its cloying embrace: at stodgy formal events, during dull lectures, or in slow-moving DMV queues.

Simple or garden variety boredom is experienced in situations that feel dully uninteresting, predictable to the point of hyper-satiety, inescapable, lengthy (the German word for boredom is, revealingly, langeweile, “long time”), and valuelessly inane. Fortunately, this kind of boredom isn’t as inescapable or lengthy as it seems when enduring it. As one commentator puts it, simple boredom is like “seasickness: it is very uncomfortable while it lasts, but it is soon over when the cause is removed.”5

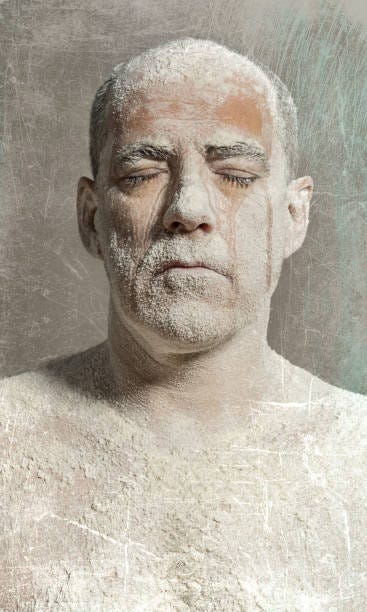

But the second kind of boredom, generally called “existential” or “profound,” not only feels but actually is lengthy. It’s not episodic at all, but instead serves as a backdrop to one’s entire life, coloring, sometimes vividly but often nearly imperceptibly, all of our experiences. (I suspect it’s what Thoreau had in mind when he wrote about “lives of quiet desperation.”) It cuts to the very core of one’s being, progressively eroding the capacity for joy and fulfillment. If simple boredom is like seasickness, existential boredom is like cancer, an inch-by-inch death of the soul, a gradual sinkage, as C.M. Cioran says, into undefinable nothingness. Or at least it can be.

Banished from One’s Soul

Existential boredom is characterized by a deep sense that there’s no value or meaning to anything in one’s own life or, indeed, to existence in general. Nothing seems interesting or even very real. The ensuing sense of weariness, emptiness, and dislocation isn’t simply spiritual or psychological. It’s physical as well. As Fernando Pessoa observes in The Book of Disquiet when reflecting on his own experience of boredom, he feels it in his very bones. It is, he writes, “the carnal sensation of the endless emptiness of things.”6 This combination of boredom’s physical and spiritual sensations leaves him hopelessly disoriented. “My boredom with everything has numbed me. I feel banished from my soul.”7

Pessoa believes that existential boredom creates a mental turgidity that prevents sufferers from thinking their way out of it. Others agree. The Norwegian author Arne Garborg characterizes boredom as “cold, weakness, a nausea of the soul …. I don’t have any better name for it than a psychic cold—a cold that has attacked the soul.”8 Philosopher Martin Heidegger uses a similar metaphor: “Profound boredom, drifting here and there in the abysses of our existence like a muffling fog, removes all things and human beings and oneself along with them into a remarkable indifference.”9

Existential boredom has been a favorite topic of philosophers and literary artists since the nineteenth century, suggesting that it’s a malaise spawned, or at least exacerbated, by modernity’s fast-paced, crisis-riven, and dehumanizing ethos.10 Goncharov’s Oblomov, Kierkegaard’s Don Juan, Dostoevsky’s Underground Man, Nietzsche’s letzter mensch, Flaubert’s Emma Bovary, Chekhov’s Yelena Andreevna, Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler, Camus’ Meursault, Sartre’s Roquentin, Miller’s Willy Loman, Roth’s Portnoy: all of them suffer from a profoundly alienating loss of meaning that engulfs them in an overpowering and sometimes self-destructive ennui.

A Fine Layer of Dust

Understandably, commentators have tended to analyze existential boredom from the standpoint of the individual sufferer rather than examining it as a social or cultural phenomenon. Søren Kierkegaard was an early exception to this trend. To his mind, existential boredom is a universal human phenomenon. He viewed garden variety episodes of transient boredom in both individuals and cultures as simply sporadic eruptions of the underlying existential malaise. True to form, Kierkegaard uses biblical images to get this point across.

“The gods were bored and so they created man. Adam was bored because he was alone, so Eve was created. Thus boredom entered the world, and increased in proportion to the increase in population. Adam was bored alone, then Adam and Eve were bored together; them Adam and Eve and Cain and Abel were bored en famille; then the population of the world increased, and the people were bored en masse. To divert themselves they conceived the idea of building a tower so high it reached the sky. The very idea is as boring as the tower was high, and a terrible proof of how boredom had gained the upper hand. Then the nations were scattered all over the earth, just as people now travel abroad, but they continued to be bored.”11

In Kierkegaard’s hands, existential boredom is an inherent human quality that’s observable throughout history. It comes across very much like original sin. In fact, he calls it “the root of all evil.”12

One of the most gripping descriptions of existential boredom as a cultural phenomenon I know comes from Georges Bernanos’ The Diary of a Country Priest. What Heidegger metaphorically calls a muffling fog and Garborg a psychic cold, Bernanos characterizes as dust.

“The world is eaten up by boredom. To perceive this needs a little preliminary thought: you can’t see it all at once. It is like dust. You go about and never notice, you breathe it in, you eat and drink it. It is sifted so fine, it doesn’t even grit on your teeth. But stand still for an instant and there it is, coating your face and hands.”13

Bernanos doesn’t quite say that existential boredom is original sin. But he does characterize it as a “leprosy” and an “aborted despair” that can infect an entire culture.14

His metaphoric description of existential boredom as a layer of dust is striking enough. But then Bernanos goes on to name what he clearly thinks is a dangerous alternative to it: frenetic activity. He concedes that if we feel the unsettling emptiness of boredom whenever we “stand still for an instant,” the temptation is to get busy doing something—doing anything. “To shake off this drizzle of ashes,” we think, “you must be for ever on the go. And so people are always ‘on the go.’”15

He’s right about this being the conventional response to boredom, isn’t he? Exasperated parents tell their bored summer vacation kids to get off the couch and go do something. The desert fathers and mothers recommended physical exertion as an antidote to acedia, the third-century Christian ancestor of modern boredom. I suspect that the Benedictine ora et labora motto has this counsel as a prophylactic subtext. In similar fashion, Immanuel Kant advised that “occupation” or activity is a cure for boredom,16 and twentieth-century philosopher Bertrand Russell likewise prescribed “excitement” and “vital activity” to counteract it.17

The Remedy’s Unhappy Side Effects

But as with all prescriptions, being “on the go” can have unintended consequences. Kierkegaard and Bernanos are quite aware of them, Kant and Russell less so. The mistake is to presume that boredom primarily displays as a somnolent lassitude that paralyzes sufferers from activity in the world. This can certain happen: think, again, of Goncharov’s Oblomov or Dostoevsky’s Underground Man. But just as frequently boredom, as Bernanos sensed, breeds an unstable sense of restlessness that can lead to rash individual actions and catastrophic collective ones.18

In attempting to escape the numb sense of emptiness induced either temporarily by simple or permanently by existential boredom, we can restlessly gravitate towards a frenetic flurry of activity that’s ultimately unfulfilling even though in the moment it may feel otherwise. It distracts, but doesn’t offer anything substantial to fill the void from which we’re trying to flee. So we flit from one project to the next, only to be serially bored by them all. Our running around shakes the dust loose for a brief moment or two, but it inevitably settles again. Divertissement, as Pascal cautioned in his Pensées, is a drug that wears off pretty quickly.19 Kierkegaard’s aesthete soon discovers that his pursuit of sensual distraction leads to the bloated boredom of surfeited passion.20

But there’s a far more dangerous side effect of the Kant/Russell prescription, one that Bernanos warned against. He published his novel in 1936, a period when the horrific destruction of the First World War and the ensuing political chaos and economic collapse plunged much of Europe into the meaningless void—the “muffling fog,” as Heidegger said—of existential boredom. In a desperate attempt at reorientation, millions of people (including, alas, Heidegger himself) embraced the mass psychosis of fascism, a movement that promised its followers a renewed sense of meaning, individual fulfillment, and collective purpose. Along the way, it encouraged policies and actions it trumpeted as muscularly heroic, but which turned out to be unspeakably wicked. Bernanos saw clearly the danger of his time’s going remedy for boredom: “To shake off this drizzle of ashes you must be for ever on the go.” For him, the treatment was as bad as the malaise. Either way, you died of boredom, spiritually and sometimes physically.

Fast forward to our own troubled time. I can’t help but think that much of the rancor and division in America today, particularly but not uniquely exhibited in the rise of the MAGA movement, is in large part a similarly frenzied attempt to throw off existential boredom’s sense of meaninglessness.

MAGAists are often accused of a cult-like blind fidelity to Donald Trump. In following him, they experience a kind of psychological rejuvenation that lifts them out of what they perceive as their humdrum lives and offers them the excitement of being part of something greater than themselves.21 Trump’s bombastic, QAnon-laced, and conspiracy-heavy rhetoric rescues them from the void of felt insignificance and infuses them with hope, energy, and an heroic sense of mission. It gives the restlessness born of their existential boredom an outlet and direction. As a bonus, it also serves up an entire menu of enemies, all named by Trump, against whom they can expend their energy and solidify their identity as MAGAists. Like its twentieth-century fascist parallel, however, this collective effort to escape existential boredom has dismal prospects both for those who embrace it and those who fall victim to it. The former are used, infantilized, and corrupted; the latter are vilified, hounded, and persecuted.

A Way Out?

At its heart, existential boredom is a spiritual malaise that assails individuals and cultures when they lose sight of genuine meaning and value. It is, as historians like Spengler and Toynbee might say, the condition of a civilization that is in decline, or at least of one in a fluid period of disorienting transition.

That ominous diagnosis is worth taking seriously. The threat of MAGA, just the latest cultural manifestation of existential boredom, is very real. But some commentators point out that, given the right conditions, existential boredom need not lead to destructive personal or collective efforts to shake off the dust. Instead, it can be a catalyst for genuine personal and social revival.

The poet and critic Joseph Brodsky, for example, argues that boredom, precisely because it’s “an invasion of time into your world system,” upsets the cart of one’s standard way of looking at the world. Consequently, it “puts your life into perspective, and the net result is precisely insight and humility.”22 Peter Toohey similarly suggests that because boredom “can breed dissatisfaction with views and concept that are intellectually shop worn,” it can serve as fallow ground for creativity.23 Heidegger also believes that existential boredom can break through the quotidian with a “moment of vision” in which new and fruitful possibilities are revealed.24

Bernanos himself argues that because boredom is a spiritual dis-ease, only a spiritual remedy—to his mind, a revived Christianity, one that doesn’t itself suffer from the dust of boredom (“My parish is bored stiff,” he has his country priest say, “no other word for it. Like so many others!”25)—can address it. And virtually everyone who reflects on the phenomenon of existential boredom agrees that a minimally effective response to it necessitates a willingness to face rather than evade through frenzied activity its sense of emptiness.

Pausing to reflect on the conditions that encourage boredom’s numb sense of emptiness is more labor intensive than rushing to fill the void with meaningless divertissment or outright destructive behavior. But unless we do, misguided attempts to shake off the suffocating dust of existential boredom will inevitably lead to the decay of individual well-being and the spawning of collective insanities like MAGA. If that happens, we can say, along with Chekhov’s Yelena, that we’re dying of boredom.

###

E.M.Cioran, Gevierteilt (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1991), p. 130. Quoted in Lars Svendsen, A Philosophy of Boredom, trans. John Irons (London: Reaktion Books, 2005), p. 110.

Anton Chekov, Uncle Vanya, trans. Richard Nelson, Richard Pevear, & Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Broadway Play Publishing, 2023), p. 29.

Michał H. Chruszczewski offers an instructive overview in his “Boredom and Its Typologies.” Culture, Society, Education Vol. 1, No. 17 (2020): 235-249.

A widely but not universally accepted typology of boredom is Martin Doelhemann’s quartet of “situative boredom,” “boredom of satiety,” “existential boredom,” and “creative boredom.” See his Langeweile? Deutung eines verbreiteten Phänomens (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1991). Curiously, Doelhemann’s insightful book has yet to be translated.

Richard Winter, Still Bored in a Culture of Entertainment: Rediscovering Passion and Wonder (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books, 2002), p. 29.

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, trans. Richard Zenith (New York: Penguin, 2003), p. 316.

Ibid., p. 161.

Arne Garborg, Weary Men, trans. Sverre Lyngstad (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1999), p. 183. Note Garborg’s reference to a “carnal” malady: “nausea.” In his novel Nausea, Jean-Paul Sartre will use the same organic word to describe existential boredom.

Martin Heidegger, What is Metaphysics? in Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: Harper Perennial, 2008), p. 99.

Because the verb “to bore” seems to have been coined only in the mid-eighteenth century, some commentators argue that boredom is a uniquely modern sensibility. While it certainly seems to be true that the existential variety is more often attested to in the last couple of centuries, it’s nonsense to deny that pre-modern humans didn’t suffer from it as well. One only need read Ecclesiastes to put the lie to that position. And simple boredom is as ancient as human experience. One early sardonic recording of it was found on a graffiti-littered wall in Pompeii: “Wall! I wonder that you haven’t fallen down in ruin, when you have to support all the boredom of your inscribers.” An instructive treatment of pre-modern boredom is offered in Peter Toohey, Boredom: A Lively History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011). Toohey, a classicist, quotes the Pompeii inscription, p. 145.

Søren Kierkegaard, Either/Or, trans. Alastair Hannay (New York: Penguin, 1992), p. 228.

Ibid.

Georges Bernanos, The Diary of a Country Priest, trans. Pamela Morris (Garden City, NY: Image Books, 1974), p. 2.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Immanuel Kant, Lectures on Ethics, trans. Louis Infield (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1963), p. 160.

Bertrand Russell, The Conquest of Happiness (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1932), pp. 57-61.

Particularly perceptive on this point is Wendell O’Brien’s “Boredom.” Analysis, Vol. 72 No. 4 (April 2014): 236-244.

I discuss Pascal’s notion of divertissement on my YouTube channel Holy Spirit Moments.

“The Seducer’s Diary” in Kierkegaard’s Either/Or.

Chris Hedges’ study of the way in which war can infuse personal and collective identity with a sense of vitality and purpose sheds light on the dynamics of the MAGA movement. See his War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning (New York: PublicAffairs, 2003).

Joseph Brodsky, On Grief and Reason (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997), p. 109.

Toohey, Boredom: A Lively History, p. 185.

Martin Heidegger, The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics: World, Finitude, Solitude, trans. William McNeill and Nicholas Walker (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1995), p. 149.

Bernanos, The Diary of a Country Priest, p. 1.

I especially the love the part about how boredom begat the world, that begat Adam, that begat Eve and so on !!