“Under the circumstances, nothing else could have happened. The simplest rules of logic proved conclusively that this did happen.” —Professor Augustus S.F.X. Van Dusen1

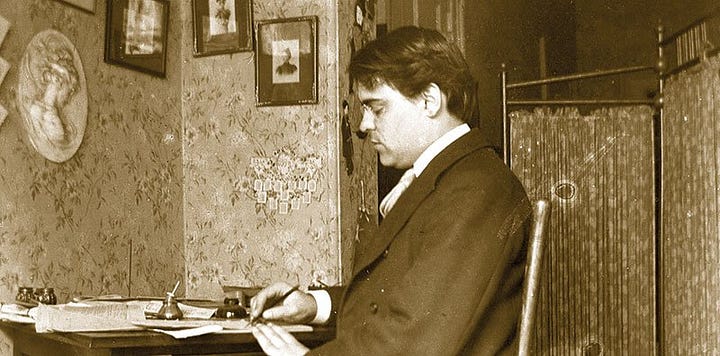

The last time Jacques Futrelle was seen, he stood on the deck of the sinking Titanic alongside millionaire John Jacob Astor. The two men were smoking cigars as they gazed on the black Atlantic waters that would soon claim them. After her rescue, Futrelle’s wife, Lily May, was interviewed by the New York Times.

“Jacques is dead, but he died like a hero, that I know. Three or four times after the crash I rushed up to him and clasped him in my arms begging him to get into one of the lifeboats. ‘For God’s sake go,’ he fairly screamed, and tried to push me towards the lifeboat. I could see how he suffered. ‘It’s your last chance, go,’ he pleaded. Then one of the ship’s officers forced me into a lifeboat and I gave up all hope that he could be saved.”2

Thus perished the creator of Professor Augustus S.F.X. Van Dusen, Ph.D, LL.D, F.R.S, M.D., M.D.S, otherwise known as “The Thinking Machine,” an armchair detective whose brilliance gives Sherlock Holmes a run for his money and whose exploits thrilled me when I discovered him as a teenager.

Two Books Merge

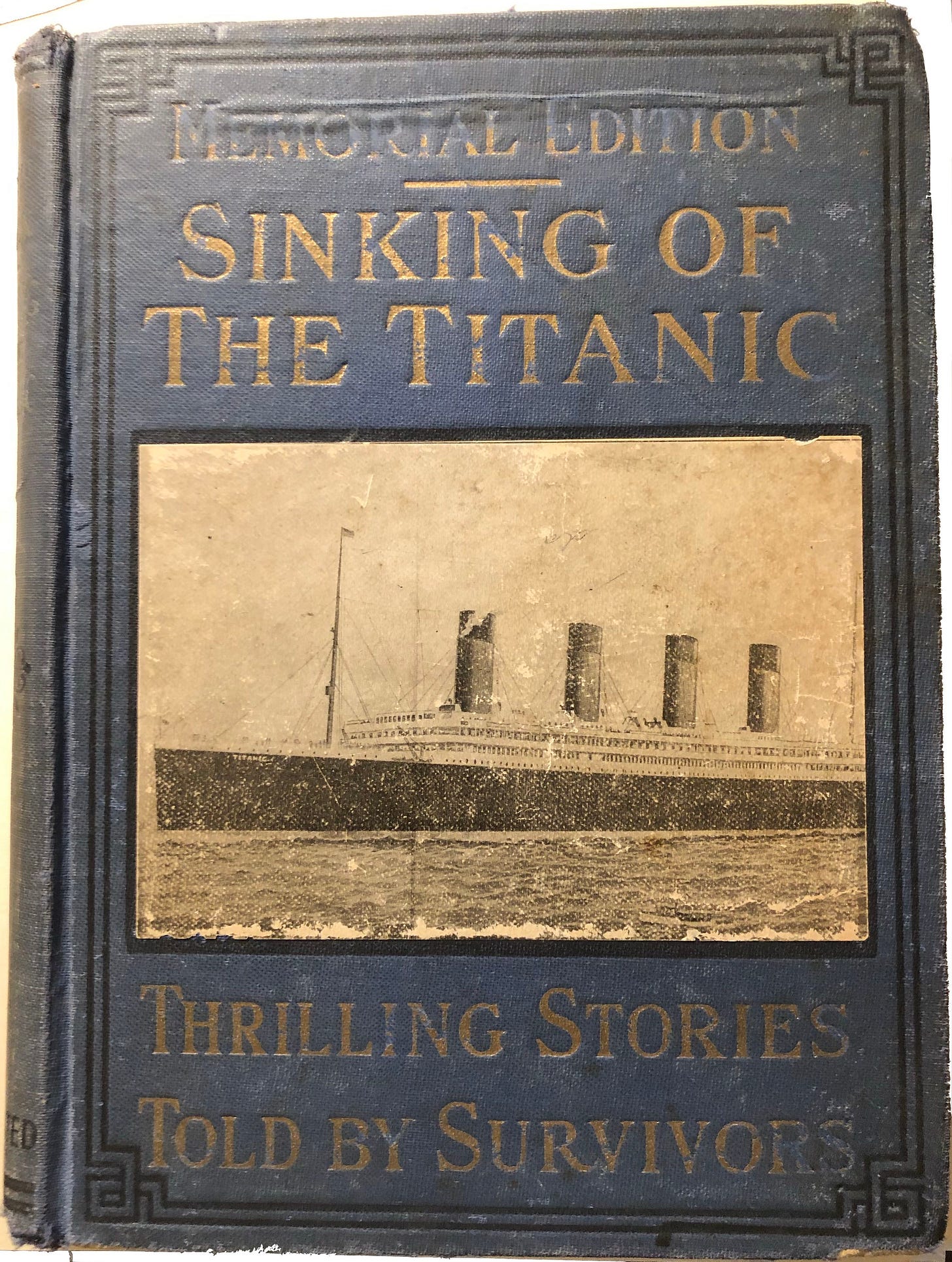

As best I remember, my maternal grandmother had two books in her house:3 a King James Bible, in which I had no interest, and a book on the Titanic disaster, which captured my imagination. Published the same year the ship went down, it was filled with photos of victims and lurid stories of what survivors experienced on that dreadful night. It fascinated me as a boy, as such horrific events have always ghoulishly fascinated humans, and I poured over it ceaselessly.

Around the same time, while still a high school freshman, I got a job in a used bookstore in my small hometown. Run by the wife of the local funeral home owner, it was a truly Dickensian affair: an ill-lit, grimy, and cavernous place stuffed with piles and piles of books begging to be sorted and shelved. I snagged my position there because I offered to work for books instead of money. Truth to tell, though, I spent as much time reading on the job as I did cataloging. My boss, God love her, perhaps bowing to the maxim that you get what you pay for, turned a leniently blind eye to my goldbricking.

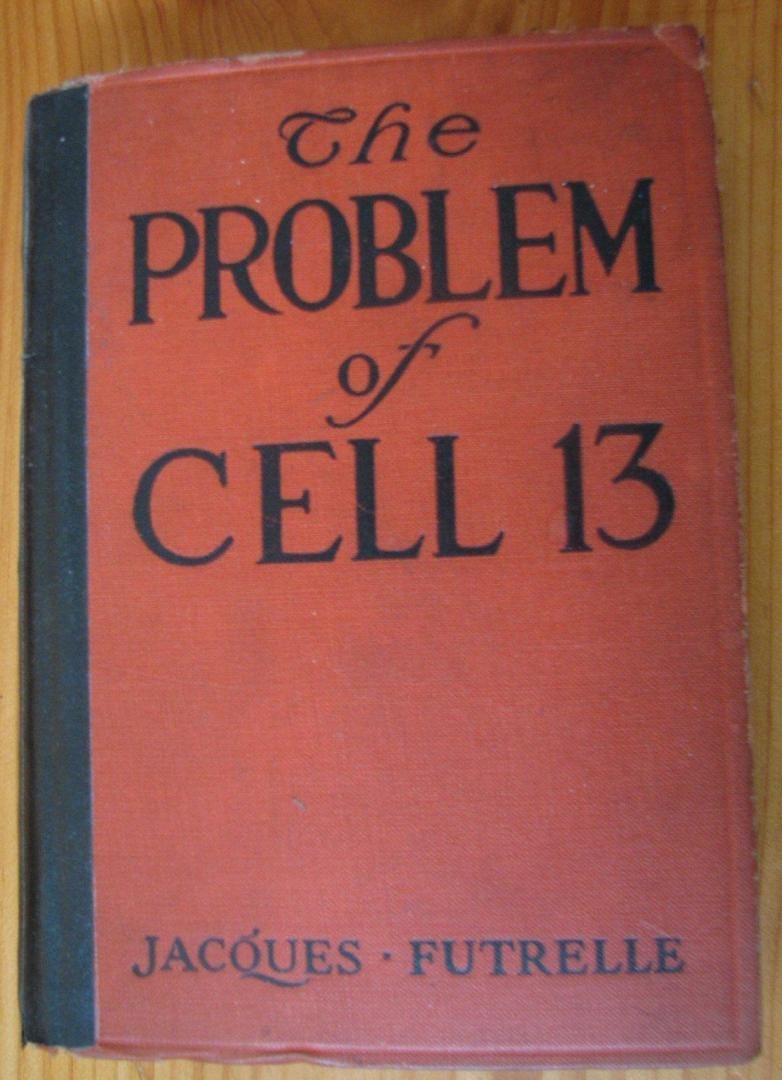

One day in the shop I ran across a volume with the curious title of The Problem of Cell 13 by one Jacques Futrelle. My hours of devouring the Titanic book paid off, because I recognized the author as one of the victims mentioned in it. Flipping through this new book, I discovered that it was a collection of detective stories. Good. Earlier reading of Conan Doyle and Émile Gaboriau had hooked me on the genre. And when I saw that the main character of the stories, Augustus Van Dusen was a professor, I was all in, since “professor” was my high school nickname (used by some of my classmates affectionately, but by others, alas, disdainfully). Titanic disaster, mystery stories, and a brainiac detective-hero: what could be better?

I’ve been reading Futrelle on and off ever since I ran across him nearly a half-century ago.

The Thinking Machine

Futrelle, who hailed from Georgia and whose real name was John Heath Futrell (he chose his pseudonym under the dubious assumption that he was of Huguenot stock), was a journalist-cum-pulp fiction author who wrote at least 50 stories and one novel featuring Van Dusen. (I say “at least” because it’s quite likely that additional ones appeared in a variety of newspapers, just waiting to be found by archival sleuths.) Van Dusen made his first appearance in late 1905 in the Boston American, inthe serialized story “The Problem of Cell 13.” The tale was an instant hit, and has been anthologized and dramatized scores of times on radio, television, and the stage.4 Futrelle, knowing that he’d stumbled upon a cash cow, began churning out Van Dusen stories by the cartful. Some of them, truthfully, are less than interesting. But when they’re good, they’re pretty darn good.

My guess is that Professor Van Dusen was inspired by Sherlock Holmes. After all, what literary armchair detective since Conan Doyle introduced his 221b Baker Street resident to the world hasn’t been? Curiously, though, a lot of personal information about The Thinking Machine is missing from the stories. We know much more about Holmes’ appearance and personality than we do about Van Dusen’s.

Here’s what we do know.

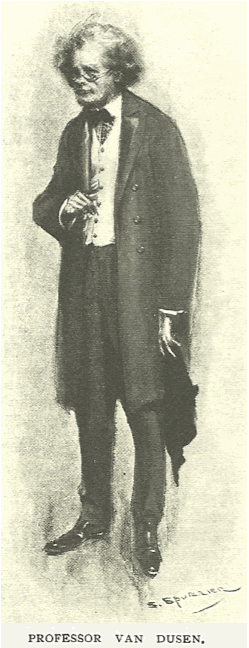

The Thinking Machine has an international reputation as a brilliant scientist, attested to by his numerous scholarly awards and honorary degrees, and he’s considered to be “a court of last appeal in the sciences.”5 A slender, clean-shaven man, pale and stooped from years of study, he wears thick spectacles through which his eyes are “mere slits of watery blue.”6

“But above his eyes was his most striking feature. This was a tall, broad brow, almost abnormal in height and width, crowned by a heavy shock of bushy, yellow hair. All these things conspired to give him a peculiar, almost grotesque, personality.”7

Above all, Van Dusen is a logician who, when presented with a mystery or crime, thinks his way through to its solution. “Two and two always make four,” he’s fond of saying. Any problem, when tackled by a logical mind, allows for just as clear-cut an assessment. Holmes tells Watson that whenever all impossibilities are logically excluded, the solution, however improbable, is revealed. Van Dusen more prosaically says that the “simplest rules of logic,” when followed, can not but lead to the truth.

You can tell whenever Van Dusen’s logical mind is at work because “tiny, cobwebby lines appear in his dome-like brow”8 and he sits “twiddling his long fingers and staring upward.”9 He’s perennially testy, impatient with the thick failure of others to follow, much less anticipate, his razor-sharp deductions. But whereas Sherlock Holmes’ impatience with Inspector Lestrade and, occasionally, Watson, is forgiveable and even endearing, Van Dusen’s irritability soon begins to grate. Futrelle is more concerned with readers being impressed by his detective hero’s intellect than he is with us liking him.

Just as Holmes has his sidekick—Watson—so Van Dusen has his, a journalist with the unlikely name of Hutchinson Hatch who serves primarily as the detective’s legman. There’s also a bumbling analog to Conan Doyle’s Lestrade: Detective Mallory, whose “usual state” is one “of retrained astonishment”10 at Van Dusen’s ingenious solutions to crimes the slow-witted Boston cop is unable to crack.

Unlike Holmes, Van Dusen refuses payment for his services as a detective. “I never accept fees,” he tells a client. “I interest myself in affairs like these because I like them. They are good mental exercise.”11 For him, it’s enough, as Sherlock Holmes might say, that the game is afoot.

But again: Futrelle isn’t as concerned with offering readers well-developed characters as he is posing riddles that need to be solved. So, for example, in the inaugural Van Dusen tale, the mystery is how a person can escape from a seemingly inescapable prison cell—the famous cell 13. Along the way, various clues are provided—for instance, the mysterious note that reads: “Epa cseot d’net niiy awe htto n’si sih. ‘T.’”12—to tantalize readers and occasionally throw them off the scent. But nothing is contrived. There’s no deus ex machina solution at the end of this or Futrelle’s other stories that perceptive readers couldn’t possibly have anticipated. Everything in the tale falls into logical place at the end, leaving the reader with a forehead-smacking “Duh! Of course! Why didn’t I see it before?!” That’s just how skilled Futrelle is.

And so it goes in all the best of his detective fiction. In “His Perfect Alibi,” the reader is asked to figure out how a tooth extraction is the key to a murder; in “The Phantom Motor,” how a speedy automobile can simply vanish into thin air; in “The Crystal Gazer,” how a magician’s crystal ball foretells a future event; in “The Missing Necklace,” “The Problem of the Stolen Rubens,” and “The Lost Radium,” how precious and protected items are purloined by villains. And so on. Frutelle’s stories aren’t just whodunnits; they’re first and foremost howdunnits, guaranteed to have readers wrinkling their brows in cobwebby fashion and thoughtfully twiddling their fingers.

Silver Standard

They’re also just great fun to read. But look. Let’s be honest. If you had to choose between reading Conan Doyle and reading Futrelle, of course you ought to go with the first. The Sherlock Holmes stories are the gold standard of armchair detective fiction. They also count, in my judgment, as very good literature. Conan Doyle knew how to write.

Futrelle, on the other hand, is an unabashed writer of pulp fiction. His stories lack the literary grace of Conan Doyle, and as I’ve already mentioned, his portrait of Van Dusen doesn’t really tell us much more about the man than that he’s a testy genius. But when compared with other detective stories featuring “thinking” detectives, Futrelle’s surely deserve to be considered the silver standard. Give me one of Van Dusen’s adventures over Nero Wolfe’s any day.

A recent collection of the best Van Dusen stories are collected in an inexpensive volume put out by Dover or you can access even more of them at Project Gutenberg if you can stand (I can’t) reading books online.

And remember: two plus two is four..

###

Jacques Futrelle, “The Perfect Alibi,” in The Great Thinking Machine: The Problem of Cell 13 & Other Stories, ed. E.F. Bleiler (Garden City, NY: Dover, 2018), p. 172. All other quotations are from this edition.

New York Times, Saturday, 20 April 1912.

My grandmother also subscribed to the weekly newspaper Grit, a publication targeting rural audiences that she read regularly from front to back. I loved it as much as she did. Much later, when it made a format change from newspaper to glossy magazine, it lost much of its charm, at least for me. I’m sure my grandmother would’ve disapproved too.

You can watch one of its many dramatizations—a pretty good one, at that—on BBC’s 1971 “Rivals of Sherlock Holmes,” Season 2, Episode 3, available on Amazon Prime.

Jacques Futrelle, “The Lost Radium,” pp. 174-175.

Jacques Futrelle, “The Problem of Cell 13,” p. 1.

Ibid.

Jacques Futrelle, “The Phantom Motor,” p. 139.

Jacques Futrelle, “His Perfect Alibi,” p. 167.

Jacques Futrelle, “The Crystal Gazer,” p. 43.

Ibid., p. 41.

Jacques Futrelle, The Problem of Cell 13,” p. 11.