I'm thinking a lot these days about how small acts of decency can defy tyranny, and I draw hope from an old, old story.

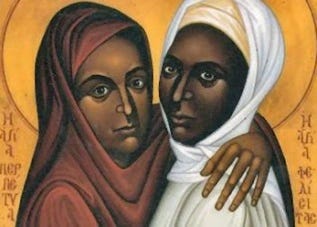

Pharaoh calls in two midwives, Shifrah1 (“Beauty”) and Puah (possibly “Girl”), and orders them to slay male infants born of Israelite women. The most powerful ruler in the world, obsessed as he is with the “danger” of “outsiders” within his borders, signs a wicked executive order and expects his subjects to kowtow.

“The midwives, however, feared God; they did not do as the king of Egypt had ordered them, but let the boys live.” (Exodus 1:17)

There are three valuable lessons for us in this simple tale.

(1) Pharaoh's wickedness is defied by two women, one of whom exemplifies beauty and the other innocence: the beauty of goodness, the innocence of a pure heart.

(2) Shifrah and Puah know that Pharaoh's command is wicked. An innate sense of decency, neither an explicit directive from God nor a pundit’s commentary, motivates their defiance. Their “fear” of God (yare'/יָרֵא) is reverence, coupled with determination, for doing the right thing.

(3) Their defiance of Pharaoh is fruitful. The executive order is disobeyed and its intended victims are spared.

Is the story historically factual? I dunno. But it attests to the splendid moral truth that from ancient times onward, people of good will resisted tyranny in small but essential ways. Others obeyed out of fear, delusion, or cruel delight. But some, like Shifrah and Puah, quietly and effectively said “no.”

Now we're called to do likewise. We could do worse than embrace these two courageous women as mothers-teachers-guides in the task of resisting the American Pharaoh history has given us.

###

The Hebrew word that may be translated as “slave woman” is shifhah. Is Shifrah’s name an intentional pun? If so, is the author suggesting that she’s a slave, even more so than the average Israelite as a member of a captive people? That would make her resistance to Pharaoh even more remarkable—and estimable.