Scapgoating and Erasure

Girardian Sacred Violence in a Medieval Mystery Play

“But the goat, on which the lot fell to be the scapegoat, shall be presented alive before the Lord, to make an atonement with him, and to let him go for a scapegoat into the wilderness.”—Lev 16:10 (KJV)

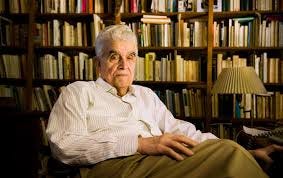

“… the erasure of memory, the desire to eliminate not only the scapegoat but everything that might remind us of him—including his name, which must no longer be mentioned.” —René Girard1

It’s late summer, 1399. Troubling news reaches your Cornwall village of Penryn that King Richard II has been deposed by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke. Like everyone else, you’re on-edge, nervously uncertain about what the future holds.

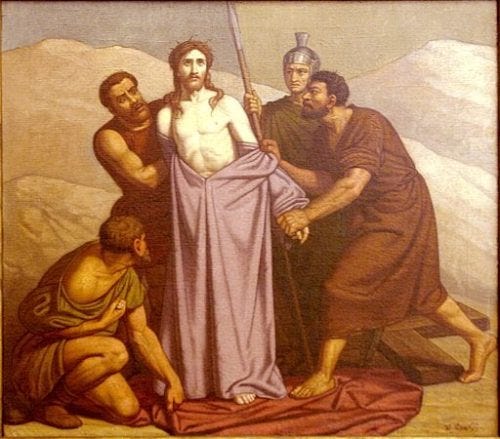

But your anxiety finds a temporary release, because in the village square the concluding acts of a three-day mystery play are underway. On the circular platform stage,2 Pontius Pilate, the villain who crucified the Lord, is arrested and tortured. Soon he’ll die and vanish into the “abyss.”

You feel a deep satisfaction at his fate and join the audience in gleefully showering him with insults and catcalls. Without your quite being aware of it, Pontius Pilate has become an outlet for all your pent-up worries and anger about the uncertain months ahead, not to mention your own personal problems. He’s your scapegoat, your sin-sponge; his fate is your badly needed catharsis. You’re happy to see him driven into the wilderness. It’s exactly what he deserves.

What you can’t know is that both the mystery play and your response to it are examples of what the twentieth-century philosopher René Girard will call “sacred violence.”

The Cornish Ordinalia

The play your fourteenth-century avatar is watching is known as the Cornish Ordinalia (“guidebooks for performance”) or the Cornish Passion Play. It belongs, somewhat uneasily because of a few anomalous features,3 to the medieval mystery play tradition.4 Probably composed in the last quarter of the 1300s by monks in the town of Penryn, it’s written in Middle Cornish with stage directions and titles in Latin. It has three distinct parts intended to be performed on a three-day cycle: “The Ordinal of the Beginning of the World,” “The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ,” and “The Ordinal of the Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Mystery plays (and their cousins, morality plays5) emerged in the early thirteenth century, descendants of liturgical skits of biblical stories performed by priests at Easter and Christmas. (The long anthems that still preface Gospel readings at Catholic Masses in these two holy seasons are remnants of them.) After Pope Innocent III proscribed clergy from acting in them, the skits, wildly popular with the laity, were taken over by merchant and craft guilds throughout English towns, especially York, Coventry, Chester, Litchfield, and Towneley. They came to be called mystery plays, not because they revealed mysteries of the faith but, more prosaically, because they were funded and performed by tradesmen or ministeria.6

The plays offered a variety of tableaux that focused on stories from the Bible or on lives of the saints. The were usually written in rhymed verse to facilitate memorization on the part of the performers, and the action was fast-paced, with scenes flowing rapidly one after one another. Most mystery plays were cycles, performed over several days, that covered bible stories from creation to the final judgment.

It would be a mistake to think of the performances as solemn occasions. They were open-air rowdy affairs, with audiences shouting, hooting, laughing or groaning in response to what was happening on stage. Vendors galore hawked beer and meatpies, kids scampered laughingly through the crowds—as, no doubt, did pickpockets. There was an air of carnival excitement whenever a mystery play was performed No doubt it was an opportunity for edification. But it was also sheer fun—or, occasionally, for catharsis.

In the Cornish Ordinale, the tableau featuring the death of Pontius Pilate—incipit morte pilati—is the penultimate scene in the final third of the cycle. It seems a bit out of place, coming as it does just after Doubting Thomas falls to his knees before the Risen Christ and right before the Ascension. Some scholars conclude, in fact, that it’s a clumsily tacked-on late addition.7 But neither its placement nor the circumstances of its inclusion are important here.

“The Death of Pilate”

The tableau about the death of Pilate is breathtakingly fast, even for a mystery play. In not quite 800 lines it describes the illness, healing, and conversion of a Roman emperor, two magical /miraculous pieces of cloth associated with Jesus, a manhunt, interrogation, and imprisonment, a suicide, a couple of disastrous burial attempts, and a culmnating horde of demons dragging a soul and body to hell.

Tiberius Caesar, the most powerful ruler alive—“I am above all people of the world, indeed”8—is stricken with leprosy. A counsellor advises him to send a servant to Jerusalem to fetch the most powerful healer alive, Jesus. But once there, the servant commissioned to find Jesus encounters Veronica, who startles him with the news that Jesus “Is dead and gone to clay / Slain by Pilate.”9

Fortunately, Veronica possesses the Sudarium, a cloth used to wipe Jesus’s sweaty face when he collapsed on his way to Golgotha and that now miraculously carries his image. She travels to Rome, meets with the emperor, and tells him,

The face of Jesus is with me,

In the likeness made by His sweat;

Whoever sees it yet,

And believes in His godhead

He needs must be healed.10

Tiberius falls to his knees, immediately professes belief (as I said, things happen quickly in mystery plays), kisses the Sudarium, and is instantly cured of his leprosy. He cries out, “There is no Lord above thee, / God without an equal!”11

Thus far, nothing is unexpected. Through a combination of faith and sympathetic magic, the power of Christ to heal and thereby subordinate Caesar is demonstrated. But things take a dark turn when Veronica abruptly demands vengeance.

Since thou art healed now

Know this well

There is no other God than He,

Yet Pilate killed Him.

Vengeance for Him take thou

That was Christ and hath now saved thee.12

Tiberius, who pivots from gratitude to fury in a flash, immediately dispatches Executioners or Torturers (the original Middle Cornish is tortor) to arrest Pilate and dispatch him to Rome so that he might be put to death. But when they bring him before the emperor, Tiberius is baffled to discover that the animus he felt towards him vanishes. In fact, almost against his will, he leaps from his throne, embraces Pilate, and declares his love for him. But wise Veronica explains what’s going on: hidden under his toga, Pilate wears the seamless garment stripped from Jesus at the Crucifixion:

From injury he [Pilate] will be free

As long as there is wound about him

The garment of Jesus.13

Christ’s garment, like the Sudarium, has a miraculous (or magical) quality: it wraps the wearer in a semblance of Christ-like goodness that no interlocutor can resist. On Veronica’s recommendation, Tiberius denudes Pilate of Christ’s robe, thereby once more recognizing him for the scoundrel he is. He orders his henchmen to take Pilate to the “lowest pit” in his prison to await “the most cruel death I ordain for him.”14 But Pilate evades the emperor’s plans by taking his own life. The irony here is apparent: because suicide is an unforgiveable sin that lands self-killers in hell, Pilate’s attempt to escape a cruel death has inflicted on himself the cruelest death of all.

Tiberius orders the corpse to be buried, lest its stench pollute the land. But when Pilate’s body is covered with gravesoil, the earth vomits it back up so intensely that the terrified gravediggers “explode” in their pants.15 Then Pilate’s body is sealed in an iron chest and submerged in the Tiber. But his presence turns the water poisonous, killing anyone who bathes in it. Finally, again on Veronica’s recommendation, the now blackened corpse is sent to sea in a ship. When it reaches the end of the world, Satan and his demons appear “To fetch, along with his soul so dear, / The body of Pilate … / To go down with us in the abyss.”16 As the unholy horde gleefully carry him off, one of them launches into an obscene song: “Yah, kiss my rear! / Its end is out here / So long behind …”17

Through Girardian Lenses

On the surface, “The Death of Pilate” is a biblically inspired and rather quaint tale about a bad man receiving his just deserts. But two startling features quickly emerge: first, the sudden shift from gratitude and praise to vengeful violence; second, the utterly villainous way in which Pilate is portrayed, one at variance with both gospel accounts and earlier sections of the Ordinalia itself. In them, Pilate comes across more as reluctantly acquiescent to Jesus’ condemnation rather than an active instigator of it. There, he seems weak, almost passive. Here, he’s the archenemy.

René Girard’s model of sacred violence can make sense of both these otherwise puzzling extremes as well as shed light on why their effect on fourteenth-century audiences might’ve been cathartic.

Girard’s foundational assumption is that human history is saturated with violence. Like Freud and Hobbes, he believes that we are fundamentally agonistic. This innate inclination is exacerbated by another fundamental human trait: the propensity for what he calls mimetic or triangular or recipirocal desire: we want what we see other people wanting. Their very desiring of something makes it desirable to us as well. What this often means is that mimetic desires lead to competition, rivalry, and violence between individuals and groups.

Moreover, it’s not only desires which are mimetic; so is ill-will.

“Reciprocity is always present in human relations, whether they are good or bad. If I hold out my hand to you, you will hold out yours to me and we will shake hands. In other words, you will imitate me. If you hold out your hand and I keep mine behind my back, you will be offended, and you will put yours beind your back as well. In other words, you will still imitate me. Even though the relationship is changing drastically, it remains reciprocal, which means imitative, mimetic. Relations of vengeance, revenge, retaliation are just as reciprocal as relations of perfect love.”18

To prevent mimetic or reciprocal ill-will from fomenting violence and rendering life solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short (to use Hobbes’ famous formula19), societies soon learn ways to ritualize and control at least some of our agonistic tendencies through relatively safe outlets such as justice systems and sporting events. But the most effective way of controlling violence is by making it “sacred”: exorcising through a ritualistic act the mimetic ill-will that threatens interpersonal and social stability.20

Sacrificing a victim on whose shoulders all the community’s anger and guilt is placed cathartically liberates everyone else, for a time anyway, from the mimetic cycle of desire, rivalry, and violence. By pinning society’s ills on a scapegoat much like the ancient practice described in the Book of Leviticus—that is, by designating a sacrificial victim as the guilty source of all society’s problems—the unrest that breeds unauthorized or unchanneled violence is deflated. It’s not our uncontrolled mimetic desires or ill-will that cause discontent and violence, but rather the perfidy of the scapegoat. Sacrificing him or her—driving them into the wilderness, erasing them from the human community—absolves and purifies the rest of us. As Girard says,

“If everybody believes in his or her guilt, in the guilt of the victim, when that victim is killed, the community will find itself free of violence (even if for only a very short time), because the violence will have been killed with that single individual upon whom the entire problem is projected. This is what we call a scapegoat.”21

The Cornish Ordinalia’s “Death of Pilate” tableau plays out this Girardian drama of mimesis, sacred violence, scapgoating, and erasure. Tiberius and Veronica represent two opposing powers, Imperial Rome and Christianity, whose respective desires for supremacy imitate and compete with one another. Their rivalry is intense because the stakes are so high: only a zero-sum victory will satisfy, with one being absorbed by the other. But in the nonce, the two parties recognize their reciprocal need of one another: Tiberius needs Jesus (and Vernoica’s intercession) to heal his leprosy and Veronica needs Tiberius (and Rome’s authority) to legitimize her faith.

To achieve their ends, the two must not only suspend hostilities against one another but become (at least temporary) allies. The reciprocal or mimetic ill-will they feel doesn’t simply vanish. As a psychic force, it’s still very much present. But because the success of their concordat depends on finding a safe outlet for it, Tiberius and Veronica turn their ire against Pilate; he becomes for them the guilty party, the source of all their grievances. Pilate “killed” the divine healer, thereby putting Tiberius’ life in jeopardy; Pilate also “killed” Veronica’s Lord. (Never mind, as already pointed out, that Pilate’s role in Jesus’ death, while important, was not as central as the tableau paints it. Scapegoats need not be, and in fact rarely are, actually guilty of what’s laid upon them.) So with breathtaking speed, the pivot is made: Pilate becomes “a devil hound” whose “stench will slay” all decent humans if he’s not destroyed.22

The violence Tiberius and Veronica will inflict on him—imprisonment, torture, and a planned (but forestalled) cruel death—becomes sacred actions to avenge the Divine Healer’s murder and so restore balance to the universe. Given the extraordinary moral weight of deicide, Pilate isn’t merely driven into the wilderness, as the Hebraic scapegoat was; he must be completely erased, disappeared as if he never existed. So neither earth nor water accepts his corpse; they protest its very presence in their midst. The only remedy—the only punishment that fits the crime—is for Pilate’s body and soul to vanish in hell’s abyss, leaving no trace behind. The erasure must be total if the land is to be purified.

“The well-oiled scapegoat mechanism generates an absolutely ‘perfect’ world, since it automatically assures the elimination of everything that passes for imperfect and makes everything that is violently eliminated appear to be imperfect and unworthy of existence.”23

And now back to your fourteenth-century avatar who, along with everyone else in the marketplace, is booing the hapless scapegoat Pilate and gleefully applauding his horrendous erasure. If Girard is right, the spectators desire Pilate to suffer because they see Tiberius and Veronica desiring it. In imitating both their desires and their ill-will, Pilate becomes the crowd’s scapegoat too, a convenient prop on which to hang their own grievances. Their little patch soon may be in turmoil because of the civil war that ominously shimmers on the horizon. Their personal affairs may be in disorder because of their own carelessness. But they can exonerate themselves of any responsibility in both the public and private spheres by vicariously joining in the fun of heaping their own anxieties and guilt onto Pilate and then driving him into the wilderness. Watching his fate play out before them strengthens their favorite way of looking at the world and their lives: somebody else, not them—not us!—is always to blame.

Seen through Girardian lenses, then, an obscure tableau of a medieval mystery play becomes much more than a quaint spectacle. It’s revealed as a speculum, a mirror in which we catch a sobering glimpse of our constant temptation to ritualized, legitimized, and “sacred” violence by which we exonerate ourselves by scapegoating and erasing others. It’s important that we be reminded of this tendency, for, as Girard warns,

“If the modern mind fails to recognize the strongly functional nature of the scapegoat operation and all its sacrificial surrogates, the most basic phenomena of human culture will remain misunderstood and unresolved.”24

###

René Girard, “Retribution” in All Desire is a Desire for Being: Essential Writings, ed. Cynthia L. Haven (New York: Penguin, 2023), p. 158.

Unlike English mystery and morality plays, which were performed on moving pageant wagons, Cornish ones were staged on stationary circular platforms.

In addition to being written in Middle Cornish instead of Middle English, the Ordinalia weaves throughout its three parts the nonbiblical legends of the Holy Rood and the Oil of Mercy not found in other English passion plays. Moreover, “The Death of Pilate” is unique to it. For more on this, see Jane A. Bakere, The Cornish Ordinalia: A Critical Study (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1980) and Victor I. Scherb, “Cornish Ordinalia” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 74-76. Also helpful are P.A. Lanyon-Orgill, “The Cornish Drama.” The Cornish Review 1/1 (Spring 1949): 38-42, and Robert Longsworth, The Cornish Ordinalia: Religion and Dramaturgy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967).

The secondary literature on mystery plays is immense. Useful overviews include Karl Young, The Drama of the Medieval Church (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1951); Hardin Craig, English Religious Drama of the Middle Ages (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960); Arnold Williams, The Drama of Medieval England (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1961); and The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Theatre, ed. Richard Beadle (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994). There are many fine translations of all the English mystery play cycles.

Morality plays, while sometimes featuring characters drawn from the Bible, focus more on virtues and vices than on scriptural stories. The two best known examples are “Everyman” and “Mankind.” For texts and excellent commentary on both, see Everyman and Mankind, ed. Doublas Bruster and Eric Rasmussen (London: Bloomsbury, 2009).

One scholar argues that the “mystery” of these plays refers not to guilds but to the liturgical skit tradition which preceded them. He claims that the word is derived from ministerium, “a performance by ministers of the Church.” Thurstan C. Peter, The Old Cornish Drama (London: Elliot Stock, 1906), p. 3.

The debate about placement is briefly discussed in footnote 9, p. 267, in Harris, The Cornish Ordinalia. For full citation, see note 8, below.

“The Cornish Passion Play,” in Medieval and Tudor Drama, ed. and trans. John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1963), p.190. Hereafter cited as Gassner.

Unable as I am to read Middle Cornish, I’ve consulted four different translations of the text: “Et incipit morte pilati et dicit tiberius cesar” in The Ancient Cornish Drama, ed. and trans. Edwin Norris. Volume 2. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1859), pp. 121-179; “The Death of Pilate,” in Everyman and Medieval Miracle Plays, ed. and trans. A.C. Cawley (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1959), pp. 235-263; the afore-mentioned Gassner translation, pp. 188-203; and “The Death of Pilate Begins” in The Cornish Ordinalia: A Medieval Dramatic Trilogy, trans. Markham Harris (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1969), pp. 221-240. Norris’ edition is bilingual; Norris’, Cawley’s and Gassner’s translations retain, with various success, the verse form of the original; Harris’ more recent translation is in disappointingly flat prose. Of the four translations, I prefer Gassner’s.

Gassner, p. 191

Ibid., 192.

Ibid., p. 193.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 195.

Ibid., p. 197.

This humorous detail is in the original Middle Cornish and rendered “explode” by Norris. (p. 157) Harris conveys it by having one of the gravediggers admit he was so frightened that he “let one” and his companion confesses to letting a “string.” (p. 233). For reasons beyond me, Cawley and Gassner display a most un-mystery-play delicacy by omitting entirely any reference to a loosening of the bowels.

Gassner, p. 203.

Ibid. The song continues with an invitation to Beelzebub and Satan to “sing the great drone bass / While I sing a fine treble.” The suggestion, since the demon has already referenced his rear, is that the “singing” is an explosion of wind from their behinds. This is reminiscent of the wind-breaking demonic chorus in Canto XXI of Dante’s Inferno:

off they set along the left-hand bank,

but first each pressed his tongue between his teeth

to blow a signal to their leader,

and he made a trumpet of his asshole.

Dante, Inferno, trans. Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander (New York: Anchor, 2000), p. 391.

René Girard, “Victims, Violence, and Christianity” in All Desire is a Desire for Being, p. 246.

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1688), I.viii.9.

Girard discusses sacred violence in many of his writings. The locus classicus is Violence and the Sacred, trans. Patrick Gregory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979).

Girard, “Victims, Violence, and Christianity” in All Desire is a Desire for Being, p. 254.

Gassner, p. 189.

Girard, “Retribution” in All Desire is a Desire for Being, p. 162.

René Girard, Violence and the Sacred, trans. Patrick Gregory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979), p. 276.