“The Catholic novel in its true sense is concerned with the impact of religious belief on an individual soul or on a human society. More correctly, it is the study of human reaction to Faith. Often it will be a story of achievement, struggle, joy, fear, success or failure on a level and in a manner that dwarfs all other human emotions and efforts.”1

Since I propose to reflect intermittently this coming year on a number of Catholic novels, it seems wise to introduce what I’m calling the Presence of Grace series by explaining, as best I can, what I mean by the term. I say “as best I can” because the designation “Catholic novel,” as Flannery O’Connor notes, is a slippery one: “The very term ‘Catholic novel’ is, of course, suspect, and people who are conscious of its complications don't use it except in quotation marks.”2 Muriel Spark, a novelist who happens to be Catholic, goes so far as to claim that “there’s no such thing as a Catholic novel, unless it’s a piece of propaganda.”3

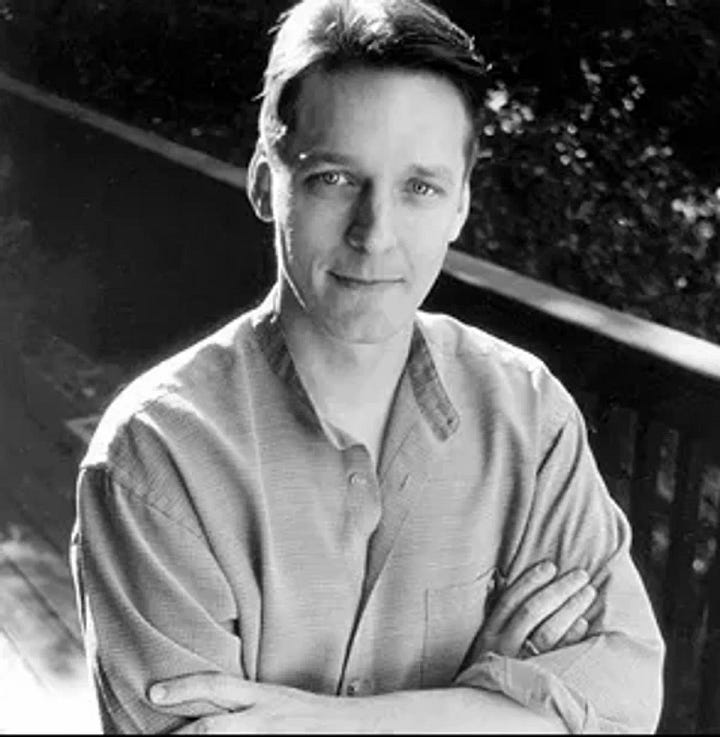

I fall somewhere between O’Connor and Spark. I think there is indeed a Catholic novel genre, and that we can speak cogently enough about it to avoid bracketing the term in scare quotes. But I also think that what binds Catholic novels together is more of a Wittgensteinian loose family resemblance than a precise Aristotelian every-and-only definition. What connects authors as diverse in style and approach as Heinrich Böll, Evelyn Waugh, Alice McDermott, Shūsaku Endō, J.F. Powers, Walker Percy, Sigrid Undset, and Ron Hansen (to name but a few!) is an unmistakably Catholic tone and a handful of identifiably Catholic themes.

The thematic features and tonal qualities common to Catholic novels will become clearer as I explore, in subsequent essays, particular ones. Nothing is more clarifying than actually diving into the novels themselves. But for now I’m content with a brief, and always open to subsequent refinement, schematic.

What They Aren’t

First, though, a few words on what Catholic novels (at least good ones) are not.

(1) They’re not exercises in Christian apologetics, nor are they devotional tracts or pious exhortations. This isn’t to deny that Catholic novels may enrich or even awaken a reader’s faith. But their essential aim is to shed light on the human spirit and its sometimes comic and sometimes tragic, but always complex, relationship with God. They’re not out to proselytize.

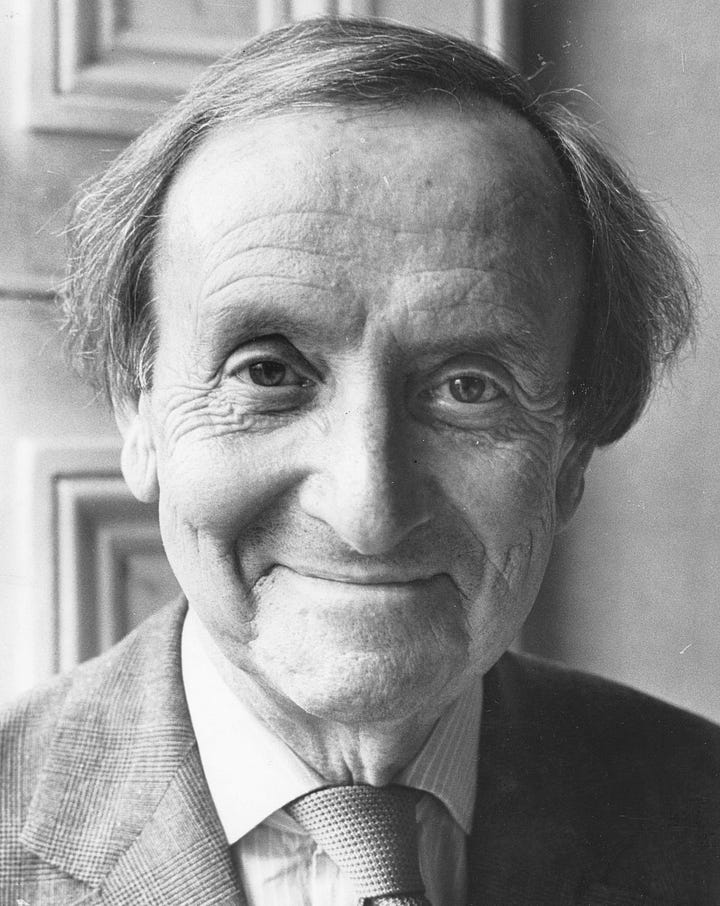

(2) Contrary to Muriel Spark, they’re not drum-beating propaganda for the superiority of Catholicism over Protestantism or non-Christian religions. Catholic novelists don’t work for the Magisterium. In fact, more than one of them have run afoul of it. Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory especially riled Vatican watchdogs.4

(3) They’re not pulp fiction. I recognize this is a judgment call that may stick in the craw of some, but I want to make a clear distinction in this series between genuinely great Catholic novels that elicit deep reflection and spiritual insight and those that, while entertaining, don’t rise to that level. That’s why I won’t be reviewing the fiction of authors such as Louis de Wohl—whose books, by the way, I devoured and enjoyed when I was young but which I now find rather insipid—the detective stories of G.K. Chesterton and Ralph McInerny, or the historical novels of Anne Rice

(4) They’re not necessarily written by cradle Catholics or Catholics in good standing (whatever that means). In a remarkably insightful article, Dana Gioia offers three categories of Catholic novelists.

“First, there are the writers who are practicing Catholics and remain active in the Church. Second, there are cultural Catholics, writers who were raised in the faith and often educated in Catholic schools. Cultural Catholics usually made no dramatic exit from the Church but instead gradually drifted away. Their worldview remains essentially Catholic, though their religious beliefs, if they still have any, are often unorthodox. Finally, there are anti-Catholic Catholics, writers who have broken with the Church but remain obsessed with its failings and injustices, both genuine and imaginary.”5

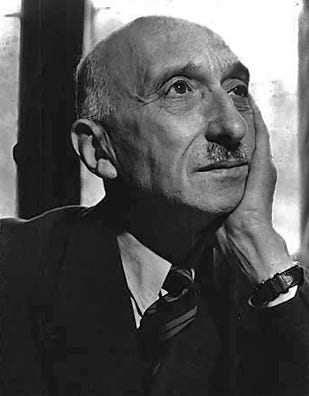

François Mauriac and Walker Percy are examples of the first, Brian Moore and Graham Greene the second, and James Joyce the third. (In Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce tellingly says that the mind of his alter ego Stephen Dedalus is “supersaturated with the religion in which you say you disbelieve.”6) But it should be noted that the boundaries between the first and second groups are sometimes blurry, and even quite orthodox Catholic novelists don’t forebear criticizing the Church’s “failings and injustices” in their work. Once again, Catholic novels aren’t propaganda.

I’d actually add a fourth category to round out Gioia’s typology: novels that are Catholic in tone and theme but written by non-Catholics. This allows us to include gems like Mark Salzman’s Lying Awake and Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop.

Ties That Bind

What are the family features shared by Catholic novels? I think these five, although not exhaustive, are the most prominent.

Catholic novels acknowledge our hunger for transcendence and mystery. In the wilderness, Jesus reminded Satan (not to mention us!) that “humans don’t live by bread alone.” We crave connection with Something that transcends and shatters the comfortable but sometimes spiritually suffocating quotidian round of our lives. We long to be wowed by deep meaning. We itch to stand awestruck before the Burning Bush, that numinous, nameless Mystery that both attracts and terrifies, discloses and reveals, flirts with and flees from us. In one of her most remarkable images, Flannery O’Connor described this elusive, risky, yet utterly captivating Something as the Jesus who moves “from tree to tree in the back of [her character Hazel Motes’] mind, a wild ragged figure motioning him to turn around and come off into the dark where he was not sure of his footing, where he might be walking on the water and not know it and then suddenly know it and drown.”7 Exactly.

Catholic novels embrace the notion of a sacramental universe. Physical reality is both good and comely (tov, as God calls it in Genesis), infused with the spirit of its Creator. Thomas Aquinas captures this sense in his maxim gratia non tollit naturam, sed perficit: grace does not remove nature, but perfects it.8 No matter how sinful humans might be, God’s creation, perfected by grace, remains tov, holy, Spirit-infused, and as such offers a multitude of visible signs or footprints of the Divine. As Catholic poet Gerard Manley Hopkins put it, “Christ plays in ten thousand places.”9

Catholic novels take human evil and human goodness, and hence sin and redemption, seriously. It’s a staple of much Protestantism as well as certain movements in Catholicism (such as Jansenism) that human will and reason are profoundly tainted by the Fall. Catholic novelists aren’t naive; they take seriously the evil humans are capable of. But—and this connects to the notion of a sacramental universe—they’re also acutely aware of the inherent God-imaged nobility of humanity. This, more than a dourly Calvinist focus on human corruption, is the traditional Catholic position; no person is so corrupt in God’s eyes as to be beyond redemption. In fact, what the world sees as sin may actually be the salvific turning point offered or at least allowed by God. For example, in Greene’s The Heart of the Matter, which I consider to be one of his most powerful Catholic novels, the main character Scobie’s “sin”—suicide—proves to be an altruistic and perhaps even holy act. When one of the novel’s characters, banking on the letter of the law, primly insists that “the Church says” suicide is a sin, a compassionate priest is quick to respond: “I know what the Church says. The Church knows all the rules. But it doesn’t know what goes on in a single human heart.”10

Catholic novels stress the religious significance of the inner life and self-scrutiny. Certainly non-Catholic novels also offer introspective portraits of characters. One immediately thinks, for example, of the work of Jean-Paul Sartre, Italo Calvino, or J.M. Coetzee. But the inner lives of characters in Catholic novels aren’t purely psychological or private. Their characters’ self-scrutiny goes, sometimes in barely discernible but nonetheless very real ways, beyond the individual ego to gesture at the Divine. This reflects the anthropology accepted by Catholic novelists: humans are amphibious creatures, part flesh and part spirit, and hence always participate, even if unknowingly, in both realms. As one commentator puts it,

“Though the material of the Catholic novelist and that of the novelist tout court is the same, the Catholic novelist sees it or ought to see it in all its dimensions, for in his [or her] eyes the central nucleus of reality, the human nucleus, is prolonged in two directions, upwards and downwards, viz.: the infra-human (the beast in us) and the supra-human (the Holy Spirit in us).”11

Most importantly, Catholic novels speak to the presence of grace in everyday life. In fact, grace can be said to be their central characteristic, the one that binds all the other features into a recognizable whole. In a God-saturated universe, grace is the ether that holds everything in place. When it comes to human lives, grace is the sometimes gentle guidance, sometimes hound-of-heaven prodding, that quickens and deepens our journey to full humanity and into God. As the protagonist says at the end of Georges Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest, “grace is everywhere.”12 Hence the title of this series.

Lights to See the World By

The American philosopher Richard Rorty argued that stories which enliven the imagination and inspire behavior are better teachers of morality than abstract treatises on ethics. They quicken empathy, in ways that the philosophers can’t, by appealing to our “imaginative ability to see strange people as fellow sufferers.”13 My own experience, both as a person and a professor, attests to the truth of his observation. Imagination is crucial to the moral life.

My experience also tells me that it’s crucial to the religious life too. Good Catholic novels are often better catalysts for spiritual discernment and growth than abstract theology or even non-fictional devotional readings. (There’s a reason why Jesus taught so often in parables.) They provide us with both panoramic views of humanity and God as well as up-close mirrors in which we catch glimpses of ourselves. We relate to their protaganists and the journeys they find themselves on. We recognize in them our own pilgrimages through faith, our own occasional senses of spiritual forlornness and despair, our ecstatic moments of connection with that Something for which we yearn. Through them we achieve a better appreciation of the complexity of moral choice, the pitfalls of pride, the power of love, and the surprising generosity of grace. Good Catholic novels show us how to imitate Christ without beating us over the head with doctrine or drowning us in pious pablum. They reveal to us what we need—what we long—to know, and live, and love.

Let’s let Flannery O’Connor have the final word. In this, as in so much else, she’s truly wise.

“All of reality is the potential kingdom of Christ, and the face of the earth is waiting to be recreated by his spirit. This all means that what we roughly call the Catholic novel is not necessarily about a Christianized or Catholicized world, but simply that it is one in which the truth as Christians know it has been used as a light to see the world by.”14

###

Kevin Quinn, SJ, “Notes on the Catholic Novel.” The Irish Monthly 79, No. 931 (January 1951): 12.

Flannery O’Connor, “Catholic Novelists and Their Readers,” in Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, ed. Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000), p. 172.

Robert Hosmer, “An Interview with Dame Muriel Spark.” Salmagundi 146 (Spring-Summer 2005): 155.

Peter Godman, “Graham Greene’s Vatican Dossier.” Atlantic Monthly (July/August 2001).

Dana Gioia, “The Catholic Writer Today.” First Things (December 2013).

James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (New York: Penguin, 1992) p. 261.

Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood, in Three by Flannery O’Connor (New York: New American Library, 1983), p. 10.

Summa Theologiae I, 1, 8 ad 2.

From the second stanza of Hopkins’ “As Kingfishers Catch Fire.”

I say móre: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God's eye what in God's eye he is —

Chríst — for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men's faces.

Graham Greene, The Heart of the Matter (New York: Penguin, 1966), p. 264.

Stephen J. Brown, “The Catholic Novelist and His Themes.” The Irish Monthly 65, No. 745 (July 1935): 4.

Georges Bernanos, The Diary of a Country Priest, trans. Pamela Morris (New York: Image, 1974).

Richard Rorty, Contingency, Irony and Solidarity (Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. xvi.

Flannery O’Connor, “Catholic Novelists and Their Readers,” p. 173.