“A cold coming we had of it

Just the worst time of year

For a journey, and such a long journey.”

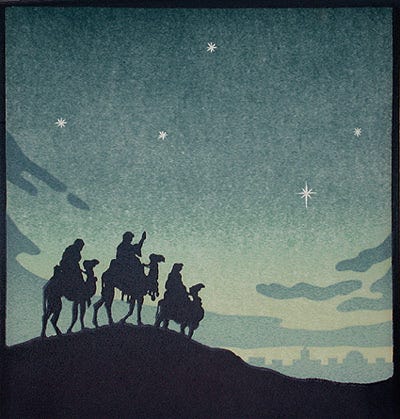

Thus begins T.S. Eliot’s “The Journey of the Magi,” a poetic meditation on the story of the Three Wise Men who travel from afar in search of the Christ-child. The Feast of Epiphany commemorates their pilgrimage.

The Epiphany story can be read in two ways: as a description of an actual historical event or as an allegory of the soul’s journey to God. Eliot’s poem, written shortly after his own midlife conversion to Christianity, explores the story’s allegorical side.

The poem is divided into three parts, corresponding to what Eliot sees as three spiritual stages through which God-seeking pilgrims pass: the hard journey to Bethlehem (searching for God), the encounter with the Christ-child (finding God), and the return home (living in God).

The poem’s speaker is one of the magi, now an old man reminiscing about the pilgrimage he and his two companions undertook years earlier.

In the poem’s first part, the magus recalls the hardships encountered along the way: refractory camels, bad weather, unreliable guides, annd filthy hostels. He remembers regretfully the pleasures he and his companions left behind.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Added to the physical hardships of the journey was the spiritual doubt that plagued the travelers with dark whispers that their trek “was all folly,” a fool’s errand, and that the wiser course would be to turn back to the comforts of home.

In the poem’s second part, the seekers arrive at their destination. But, oddly, the magus doesn’t describe the actual encounter with the infant Jesus. He simply recalls that he and his companions “arrived at evening, not a moment too soon.”

Finally, in the poem’s third part, the magus confesses that although he would gladly make the journey again, he isn’t quite sure what to make of it. The messianic birth heralded by the star also spelled a kind of death for him and his companions.

We returned to our place, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation

With an alien people clutching their gods.

Many of us think of conversion as a one-off event that dispels all our religious doubts and suffuses us with uninterruptable joy.

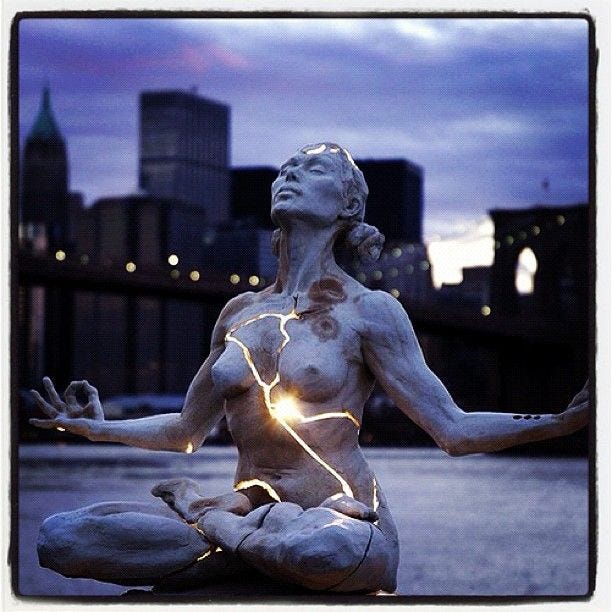

But this is extremely rare. Much more commonly, conversion is a halting and laborious process so fraught with mental and spiritual uncertainty—although also offering moments of illuminating grace—that we’re tempted at times to chuck the whole thing. Not only do we frequently feel as if we’re groping in the dark, but we’re also faced with the painful task of repudiating engrained behavior and beliefs that stand between us and God.

This is the initial stage of the soul journey, exemplified by the first part of Eliot’s poem.

When we do make the breakthrough to faith—the second part of the poem as well as the second stage of soul journeying—we often find it difficult to pinpoint actly when it occurred.

We awaken one day to discover that we’ve arrived at our destination: belief in God. The Spirit blows where it will, mysteriously, bafflingly. This explains why Eliot wisely refrains from having the magus say anything about his encounter with the infant Jesus. Words are inadequate to describe such an experience.

It’s tempting to think this is the end of the journey for those of us who search for God. But it isn’t. As Eliot says in the concluding third of his poem, conversion is Janus-face, pointing to birth on the one hand but death on the other.

Discovering God is a spiritual rejuvenation, but it also creates an unsettling sense of alienation from a culture—what Eliot calls the “old dispensation”—that genuflects before the idols of egoism, wealth, and power. Birth in God and living in God means an ongoing dying to worldliness, and dying is always a painful process. But the death that the magi experienced is also one for which we yearn.

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death ….

I should be glad of another death.

Eliot’s poem reminds us that soul journeying is more complex than we might imagine. But it’s worth undertaking because it ultimately brings us to God. That’s the meaning behind the story of the three magi. That’s the gift of Epiphany.1

###

Adapted from my Faith Matters: Reflections on the Christian Life (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2019), pp. 204-206. First published on Substack one year ago.

Thank you, Kerry, for this profound meditation. We read it during our morning prayer and it provided us with much to think about.

.particularly the 3 stages of encountering the Christ...our spiritual journey. It is a very helpful reflection...we appreciate it

Hi Kerry, I so love this. I have loved Eliot yet have often not found such sensitive elucidation as you offer here. Thank you so very much.