“The life of every man is a diary in which he means to write one story, and writes another…”1

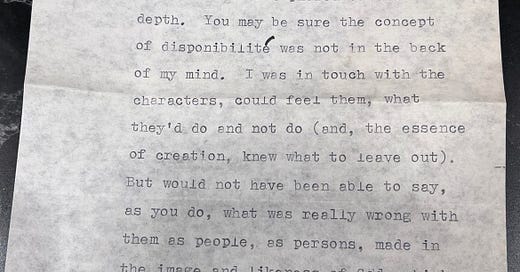

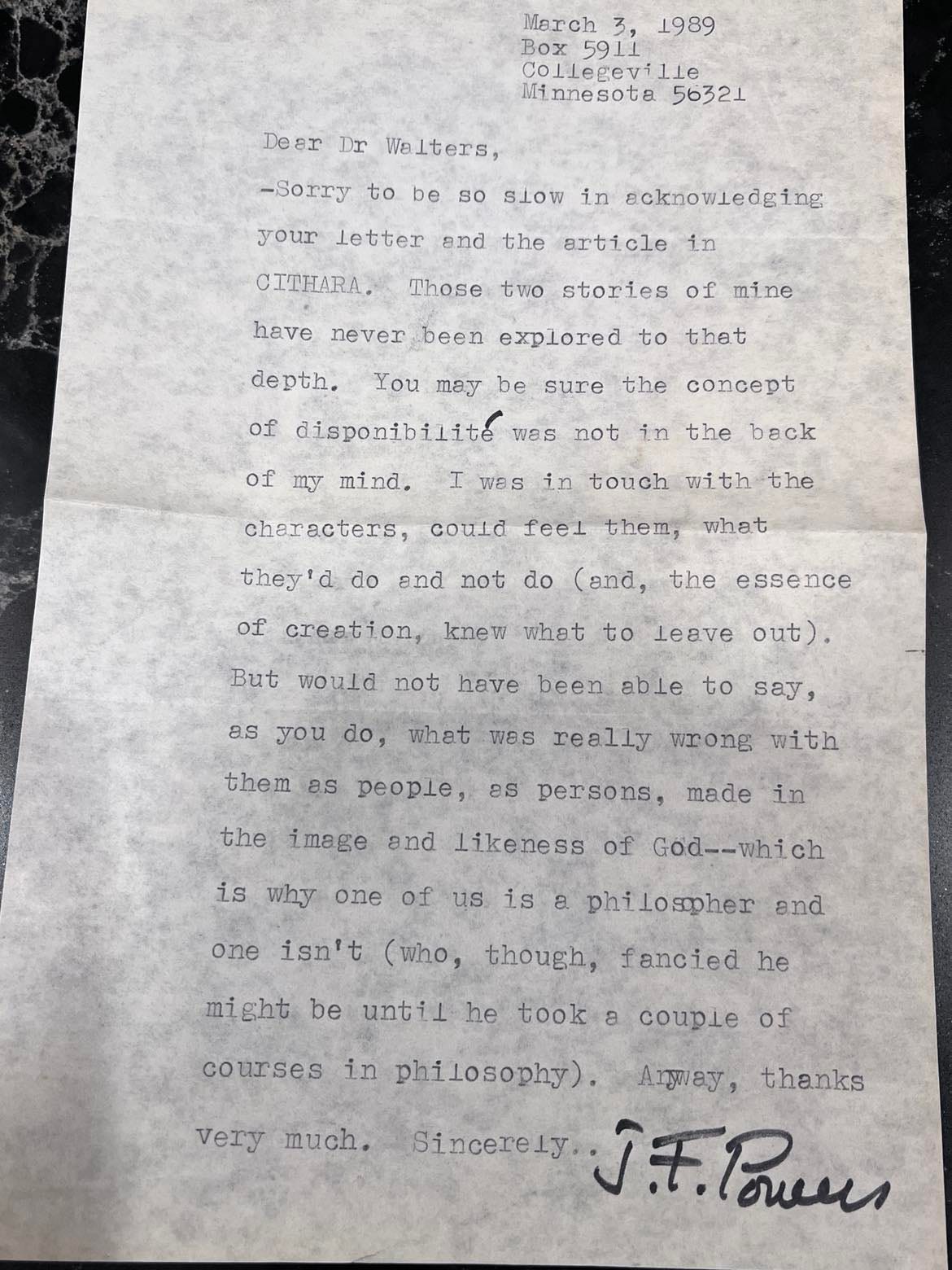

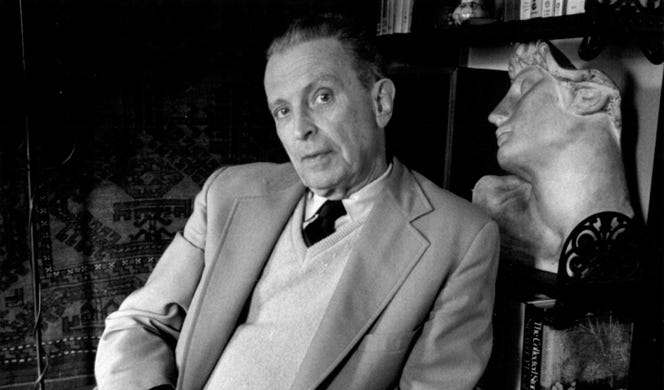

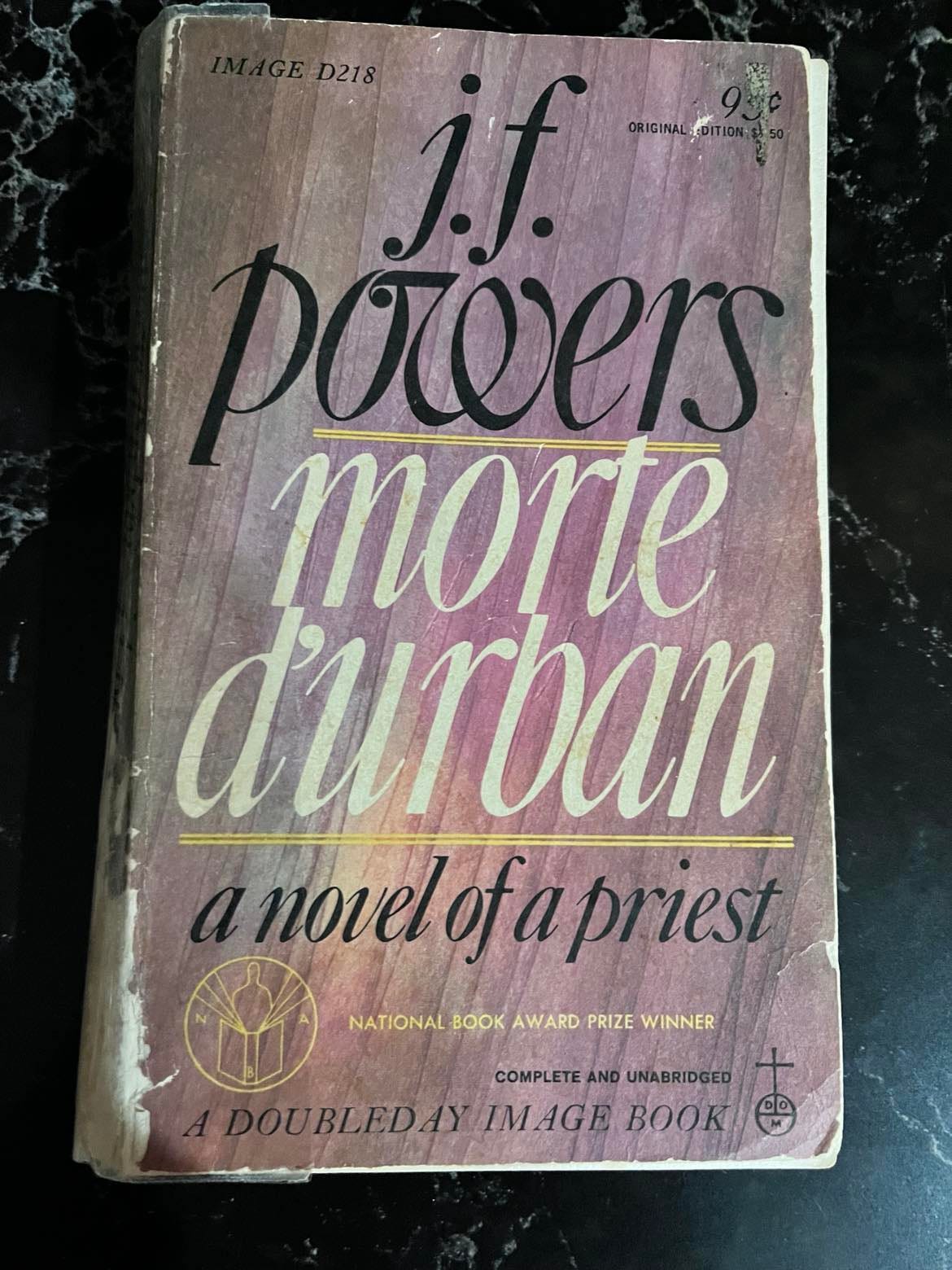

It’s been thirty-five years since I published a rather insignificant article2 about a couple of J.F. Powers’ short stories. As an untenured assistant professor of philosophy, I’m sure I wrote the thing partly out of publish-or-perish anxiety. But I also genuinely admired Powers’ work, so much so that when the piece came out I sent him (talk about chutzpah!) a copy. Much to my delight, he actually responded a few months later with a note every bit as wry in tone as his fiction is. I still treasure it.

J.F. (James Farl) Powers is barely remembered today. But I think he’s one of the finest Catholic novelists this country has ever produced, right up there with Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy. He never published much in his lifetime: two novels and three collections of short stories are his entire oeuvre. But his first novel, Morte d’Urban, won a National Book Award (beating out Nabokov, Updike, and Katherine Ann Porter), his second, Wheat That Springeth Green, was nominated for another one, and his shorter fiction is uniformly praised. No less a luminary than O’Connor praised him as “one of the country’s best short story writers.”3

Even so, his books were never bestsellers—Morte d’Urban, despite its prestigious award, retailed barely 25,000 copies4—and all his work was out of print by the time he died in 1999.5 He fell, as one regretful commentator put it, into “obscurity and neglect.”6 In a snarky review of a posthumous collection of Powers’ letters, a less sympathetic critic called him “naive” and wondered why he bothered to write his “narrow and dated” fiction “in the first place.”7 In short, good riddance.

Part of the explanation for Powers’ obscurity is that the protagonists in both his novels and most of his short stories are clergy, and priests, thanks to sexual scandals and secularization, are in bad odor these days. That accounts for the charge of narrowness. Nor does it help that most of his stories are set in the 1950s and 1960s, either prior to Vatican II or in its immediate aftermath—hence their “dated” quality.

But neither of these are good reasons to write off Powers, because the primary theme that cuts across all his work is a timeless one: the call for Christians to navigate being in but not of the world. Powers writes about priests because this is a task which, paradoxically, their very vocation as shepherds makes all the more difficult. They must, says Powers, juggle being priest-priests, priest-promoters, and priest-operators. I didn’t fully appreciate the impossibility of satisfactorily doing so, even after multiple readings of Morte d’Urban, until I actually served a parish. I suspect most laypersons never do. How fascinating that Powers, a layman himself, saw it so clearly.

Falling Upwards & Falling Downwards

The usual interpretation of Morte d’Urban is that it’s the story of a priest, Father Urban Roche, who experiences, through God’s grace and a few hard knocks, a spiritual death—the morte of the title—and subsequent spiritual rebirth. This trajectory—a kind of spiritual rags-to-riches trope—is favored, perhaps, by Sunday School tracts, but not by Powers.8 The arc of Urban’s life is much more complicated than that. By the end of the novel, it’s not clear if he’s fallen upwards, downwards, or a bit of both. It’s Powers’ way of getting across the truth that for most of us, ambiguity is baked into our journeys through life and to God.

Upwards. Chicago-based Father Urban, “fifty-four, tall and handsome but a trifle loose in the jowls and red of eye,”9 belongs to the (fictional) Order of St. Clement. From its very start, it “labored under the curse of mediocrity …. The Clementines were unique in that they were noted for nothing at all.”10 The Order’s one shining light is Urban, an eloquent preacher and retreat leader who travels the midwest to raise money and encourage vocations. Along the way he woos a number of lay Catholics with deep pockets—Billy Cosgrove being the biggest catch—to bankroll his vision of what the Clementines might be. His dedication to the Order is genuine, but he’s also fond of the perks—expensive dinners, fancy hotel rooms, the best cigars and scotch—provided by rich benefactors used to living the good life. “He was true to his vow of poverty—to the spirit, though, rather than the letter. For someone in his position, it could not very well be otherwise.”11

Just as Urban thinks he’s making progress, his Provincial (jealous of his popularity? concerned for his spiritual well-being?) sends—or, in Urban’s opinion, exiles—him to a rural startup in Duesterhaus, Minnesota. The place deserves its name (“Gloomy House” in German): “Duesterhaus was a one-stoplight town. New and old yellow lines ran at cross purposes on the pavement, marking a recent change from diagonal to parallel parking. The main street was a state highway. The drugstore was the bus station.”12

Urban’s new home, the fledgling retreat mission of St. Clement’s Hill, is no more impressive. Housed in a drafty mansion with a dubious history (including a murder and suicide), the Hill is run by Father Wilfrid, a penny-pinching do-it-yourselfer whose on-the-cheap repairs generally end in disaster. He’s also a pedant who offers sententious opinions on everything from rodents and trees to how Urban can keep warm in Minnesota’s frigid winter months—while indirectly chastising him for not finishing the fish served up ad nauseam at every meal. “Now you take your Eskimos. They never catch cold, you’ll notice, and I’ll tell you why. They can’t afford to. Even the dumbest Eskimo knows he’s got to take care of himself. So what does he do? He eats plenty of fish.”13

His other companion at the retreat is Father Jack, an unassuming, simple man who defers to others out of a mixture of kindness and humility, uses “outdated language, words like ‘flapper’ and ‘sheik’ and ‘applesauce’ (as an oath),”14 and is a lover of checkers. Jack is an utterly unnoticeable man, one of the Clementines who, Urban thinks, earns the Order its reputation for mediocrity.

To his credit, Urban tries to bend the knee to his new situation. But he’s miserable until the opportunity arises to serve as supply pastor at St. Monica’s, a local church. This is a task he can sink his teeth into, and his people skills and full-speed-ahead work ethic soon have the rather moribund parish humming. But his time there also underscores the dilemma of ordained life that is the novel’s central theme: how to sustain an inner life while at the same time running a parish, the cleric’s in-but-not-of-the-world mandate. It’s a concern that appears again and again in Powers’ fiction.

At one pole of the end-but-not-of spectrum is Father Chumley, the curate at St. Monica’s. He’s a contemplative sort who prefers to spend most of his time in prayer. At the other end is the local bishop, “dear James” as one of his monsignors disdainfully refers to him, an administrator in mitre and cope whose chief concern is enlarging and enforcing the Church’s power in his diocese. Somewhere in between is Urban, who recognizes the importance of contemplation, even though it’s not his forte, but also the pastoral necessity of supervising a parish, paying the bills, maintaining friendly relations with the broader community, shepherding troubled souls, dealing with malcontents, administering the sacraments, and keeping on the bishop’s right side. For him, it’s not enough to be either a “priest-priest” contemplative or a “priest-promoter” like the bishop. A good priest has to be both Mary and Martha.

“Should be two kinds of men in every busy parish. Priest-priests and priest-promoters.”

“I’d say a man has to be both. At least a man can try. Sometimes that’s the most a man can do. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be placed in the position we are, placed under the necessity of both.”15

But there’s a third ball that needs to be juggled as well, further muddying the in-but-not-of mandate. As Sally Hopwood, one of the novel’s characters, astutely tells Urban (right before, by the way, she unsuccessfully tries to seduce him), “You’re an operator—a trained operator and an operator in your heart.”16 Fair enough. If a priest-priest is going to be a successful priest-promoter, he has to be something of a showman as well. He has to know how to sell his product—or, put in less crass (or at least more traditional) Pauline language, he must learn how to be all things to all men and women (1 Cor 9:22b): counselor, sportsman, cheerleader, exemplar, salesman, confessor, and so on. It’s an exhausting role that can twist over-worked and under-prayed priests into Elmer Gantrys or Babbitts.

Urban’s ultimate triumph as operator and promoter is in convincing Billy to buy farmland adjacent to St. Clement’s Hill so that a golf course can be added to the floundering retreat center. His intention is to attract a “better”—namely, richer—clientele, and it works. The course, including its “new shrine of Our Lady below No. 5 green,”17 is a hit. Before long the woebegone Hill is rolling in dough and Urban, basking in its success, is proud that his wheeling and dealing, performed “of course, for the order,”18 has paid off. The Order of St. Clement is on its way.

Downwards. There reaches a point when juggling the three priestly roles wears thin for Urban, as it does for many actual pastors, and almost in spite of himself—surely a grace-moment—he begins focusing more on being a conscientious priest-priest and less on a handshaking and back-thumping clerical operator. The consequences, given the way the world is, are dramatic but predictable. First, he alienates the wealthy Mrs. Thwaites, a self-absorbed harridan, by gently suggesting that she cease abusing her Irish maidservant. Then he infuriates Billy Cosgrove, the millionaire who’s also a petulant bully, when he prevents him during a fishing vacation from cruelly drowning a deer. Finally, Urban enrages the previously mentioned Mrs. Hopwood, an heiress, by refusing her sexual advances.

In each of these three scenes, Urban winds up literally abandoned, symbolizing that the three moneybags he’s spent so much time and energy courting have cut him loose. Mrs. Thwaites leaves him carless in the middle of nowhere, Billy dumps him in a river and motors away, and Sally strands him on an island. All of these situations have comedic elements—Morte d’Urban is a very funny novel in places—but they’re also brutal reminders of what can happen when a priest acts like a priest with laypeople who want something else from him.

The coup de grâce comes on the golf course Urban’s so proud of. While playing a round with “dear James,” the inept bishop manages to slice his ball right into Urban’s head, knocking him cold. The bishop, who’d been kicking around the idea of seizing and transforming St. Clement’s Hill into a diocesan seminary, backs off after injuring Urban, either out of panic or guilty conscience. When one of Urban’s friends sees that the retreat center has received an unexpected reprieve, he exclaims, “An act of God, if ever I saw one.”19

He’s more right than he knew. The knock on Urban’s head is like a bolt from heaven. It breaks his health—intense periodic headaches weaken both his physical and mental strength—and radically transforms his life. The old go-get-’em Urban, the priest operator and promoter, vanishes. There’s a special irony—or, better, tragedy—in this, because soon after the accident he’s elected Father Provincial, largely because younger Clementines believe what he’s been saying about himself for years: that he’s the man to put their Order on the map. Urban now has the power he’s always wanted. But now he lacks the physical stamina or will to use it.

At one point in the Latin ceremony that consecrates his new standing in the Order, he’s told “Surge, Urbane!” “Rise, Urban!”20 Rise to greatness in the new authority entrusted you by God and your brother Clementines! But he can’t. Urban’s on a downward personal trajectory, and his inability to lead—“seldom had a new Provincial so badly disappointed the hopes and calculations of men”21—more than sustains the Order’s reputation for mediocrity. Everything that Urban worked for prior to the accident and his election falls apart. To top it all off, “dear James,” apparently no longer deterred by the memory of his unfortunate golf swing, renews his move on St. Clement’s Hill.

Urban’s episodic headaches, which make him reluctant to meet with people, ironically “gained [him] a reputation for piety he hadn’t had before, which, however, was not entirely unwarranted now.”22 True enough. But at the end of the day, he comes across as more broken than saintly. The Urban we find at novel’s end is a shadow of the man we met at its beginning.

Known to God Alone

As I suggested at the start of this essay, Powers’ story of Father Urban doesn’t have a cheery they-loved-happily-ever-after ending. It’s helpful to remember that the novel’s title is an homage to Malory’s fifteenth-century Morte d’Arthur, which likewise doesn’t conclude well. King Arthur is slain, his source of power, sword Excaliber, is cast away, and the dream of Camelot fades.

But although Morte d’Urban doesn’t end happily, I think it does end on a good and even godly note. Urban’s success as a priest-promoter and priest-operator was a falling upwards: successful upward mobility in the eyes of the world and the institutional Church, but a way of being that bordered on moral and spiritual failure in the eyes of God. His subsequent falling downwards, the collapse of his projects and the accident’s sapping of his energy, didn’t transform him into a plaster saint with piously upraised eyes, even if it did encourage a bit more inwardness. Instead, it gave him physical pain, mental confusion, and an unaccustomed passivity. On the surface, both chapters of Urban’s life end in failure.

But it’s precisely this, I think, which makes the ending of Powers’ tale powerfully godly. The falling-upwards Urban, convinced that his Order was characterized by mediocrity, made it his mission to fix things through hard work and selective schmoozing. He wanted the Clementines to be players every bit as noticed and admired as the Jesuits or Benedictines. He failed to understand that what he condemned as mediocrity was in fact the anonymity of Thérèse of Lisieux’s “little way,” and that this was his Order’s special charism, the gift it offered to the world. The Clementines, “noted for nothing at all,” served God silently, humbly, namelessly and behind the scenes, putting one foot in front of the other, content in their quiet, unflashy way to be invisible servants, not seeking glory or craving recognition, but simply getting the job done.

In this sense, Father Jack is the real spiritual hero of the story. He lives the nothing-at-allness, the ego-emptiness, of a servant. As he revealingly says of his place in the Order, “I don’t much care what happens to me.”23 This is neither a cynical nor despairing declaration, but a good-hearted statement of willingness to accept and persevere in whatever task is given. This is being in but not of the world.

To the world and the Church, and maybe even at times to themselves, Clementines come across as third-rate fumblers, a bit lackluster, a bit confused, a bit quaint, a bit pointless. But their genuine worth is seen by God. It’s only after his falling upwards and downwards rollercoaster ride finally brings him to the point of contentment with little-way anonymity that Urban becomes what God intends him to be: a good Clementine.

And therein lies a way out of the uncomfortable situation so many pastors find themselves in as they try to juggle contemplative prayer (Mary) and busy parish ministry (Martha). What’s ultimately important isn’t so much growing the church or keeping up with the physical plant, making sure that the altar flowers get ordered, or even that Sunday’s homilies are all spiritual gobstoppers. Nor is it necessary to strive for a prayer life that leaves the saints speechless with admiration and envy. The way to jump off the clerical hamster wheel of straining to be both Martha and Mary, to be the superpriest who is simulatenously spiritual guru, wheeler-dealer, and expert administrator, is simply to be content with the gifts and opportunities God has given you. What’s important is the little way, putting one foot in front of the other, patiently, silently, nonjudgmentally, anonymously, serving God and God’s people, expecting nothing, accepting whatever comes, content to be known to none but God. That’s the one thing needed. The rest, as Urban discovered, is distraction.

In this funny, touching, and illuminative novel, Powers’ message is that pastors could do worse than aspire to the Order of St. Clement. All priests could do with an occasional “act of God if ever I saw one” konk on the head. For that matter, so could the entire Church.

###

This passage from J. M. Barrie serves as the epigraph to J.F. Powers, Morte d’Urban (Garden City, NY: Image Books, 1962).

“The Virago and the Bully: Soul-Paralyzed ‘Spouses’ in J.F. Powers’ Prince of Darkness,” Cithara: Essays in the Judeo-Christian Tradition 28 (1988): 14-27.

Flannery O’Connor, The Presence of Grace and Other Book Reviews (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1983), p. 168.

Michael O’Connell, “An Effective Influence for Good”: A Reconsideration of J.F. Powers’s Morte D’Urban.” American Catholic Studies, Vol. 129, No. 3 (Fall 2018): 55-73.

Happily, NYRB Classics reissued his novels and short stories shortly after his passing.

Donna Tartt, “The Glory of J.F. Powers,” Harper’s Magazine (July 2000), 69.

Paul Elie, “Bartleby on the Prairie: The Unspent Life of J.F. Powers,” Harper’s Magazine (September 2013).

Truth to tell, though, this actually is the trajectory of Powers’ second and rather disappointing novel, Wheat That Springeth Green.

Morte d’Urban, p. 23.

Morte d’Urban, p. 20. Even the Order’s publishing house, named after the instrument of its founder’s martydom, speaks to its downward mobility: Millstone Press.

Ibid., p. 16.

Ibid., p. 41.

Ibid., p. 59.

Ibid., p. 29.

Ibid., pp. 144, 145.

Ibid., p. 278.

Ibid., p. 198.

Ibid., p. 199.

Ibid., p. 233.

Ibid., p. 301.

Ibid., p. 306.

Ibid., p. 308.

Ibid., p. 33.