Thomas Aquinas, Badass

badass (noun, slang): cool, cutting-edge, adventuresome, edgy, enviable

In Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, a fourteen-year-old lad listens impatiently as his mother reads the story of a teenage Mexican saint and martyr named Juan.1 Her expectation is that her son will be edified. But the tale is so mawkishly pious, like so many standard lives of the saints, that the boy is disgusted. Greene captures its off-putting hagiographic tone perfectly:

“We must not think that young Juan did not laugh and play like other children,” the mother reads, “though there were times when he would creep away with a holy picture-book to his father’s cow-house from a circle of his merry playmates […] One day his father thought that he had told a lie and beat him. Later he learnt that his son had told the truth, and he apologized to Juan. But Juan said to him, ‘Dear father, just as our Father in heaven has the right to chastise when he pleases . . . ”2

And on and on and on: Juan, the perfect martyr, Juan the perfect saint, Juan the perfect Christian role model for all boys. Finally the lad can’t endure any more of the cloying treacle. Jumping up, he furiously shouts, “‘I don’t believe a word of it, not a word of it!’” When his shocked mother orders him out of the room, he departs sputtering,“‘Anything to get away from this—this—!’”3

I’m with him. I hate that centuries of piety have smothered the fire that animates genuine saints, turning them into insipid caricatures who gaze ever heavenward, hands devoutly clasped, pursed-lipped-gazing-on-God expressions on their faces. How can we possibly relate to these do-gooders who somehow manage to pull off being simultaneously smarmy and wooden? Why would we want to? They make you want to belt out a few choice obscenities just to clear your palate of their sickly sweetness.

Real saints aren’t saccharine. They’re uncanny, unpredictable, wild, disarming, and sometimes barely likeable. They live on the edge, forsaking the comfort zones the rest of us wrap ourselves in. Their wrestling with God leaves them wounded and raw. Perhaps that’s why we tend to domesticate them; their undiluted reality is too much for us. But if we brace ourselves to heed their real stories rather than their overly-pious hagiographies or their prayer card avatars, they have something valuable to teach us about being spiritually and personally alive. If nothing else, they teach us to be daring, to take risks.

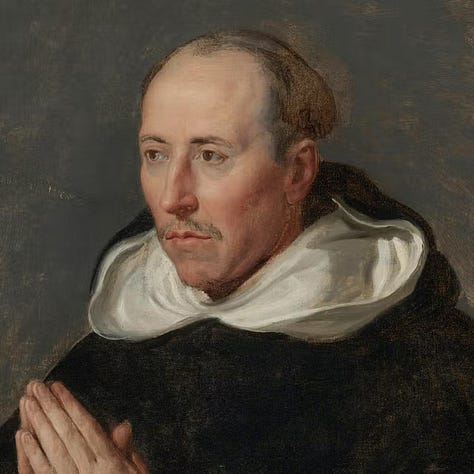

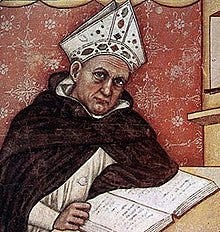

One of these saintly risk-takers is Thomas Aquinas, whose feast day falls later on this month. But just look at what we’ve done to him:

I know that images like these, as well as the pious stories that inspire them, don’t mean to be so insipid. They really try to convey, albeit in a ham-fisted way, a sense of Thomas’ holy devotion and dedication.4 But they mainly succeed in portraying him as an unctuous prig who evokes much the same reaction in me that the lad in Greene’s novel had to Juan, the perfect boy saint.

That’s a shame, because Thomas was no Uriah Heep. He oozed vitality and disarming honesty. He was a bold and occasionally bare-knuckled adventurer in both his personal life choices and his thought.5 He was, in short, a cool badass whose defiance of conventional norms shocked his family, infuriated his foes, and infused new energy into what had become a somewhat weary style of philosophizing and theologizing. Understanding this not only rescues his powerful personality from the prison of prayer card schlock. It also enriches our appreciation of his colossal intellectual achievement.

Badassery 1: Thomas Becomes a Fanboy of Aristotle’s

As the youngest son of a minor noble family, Thomas was destined for a career in the Church. But not just any career. His uncle Sennebald was abbot of Monte Cassino, one of the oldest, wealthiest, and most prestigious Benedictine monasteries in Christendom, and it was assumed that one day Thomas would take his place. So in 1229 the five-year-old boy was sent there to be schooled in Latin, grammar, and the rhythms of cloistered life. He remained at Monte Cassino for a decade, leaving in 1239 to study at the University of Naples. It proved a turning point in his life.

The university was established in 1224, the (likely) year of Thomas’ birth, by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. It was intended by Frederick, who feuded endlessly with the Church, to be a foil to the rival papal studium in Bologna. Philosophy and the arts, not theology, were the primary courses of study. Under Frederick’s protection, the imperial university’s professors dared to openly teach an ancient philosopher under suspicion by Rome: Aristotle. “Virtually nowhere else in the West,” writes one commentator, “was it possible to encounter Aristotle so intensely and so comprehensively as in the city of Naples.”6

Thomas’ primary tutor seems to have been one Peter the Irishman, a devotee of Aristotle’s philosophy and logic who had little use for or interest in theological questions. So Thomas was influenced in his most impressionable years by someone for whom Aristotle’s philosophy offered a breathtakingly new way of reading reality: from the ground up, as it were, starting with the concrete natural world of everyday experience rather than speculation about a transcendent realm.

Traditionalists schooled in monastic theology who tended to view the natural world with suspicion fought it tooth and nail, but the thirteenth-century rediscovery of Aristotle inaugurated something of an intellectual paradigm shift in the Latin West. Aristotle’s fans, including Thomas, saw him not as a relic from the ancient past, but as an astoundingly cutting-edge mentor. Before long, students at all of Europe’s universities were clamoring for instruction in his writings. “The philosopher,” as he came to be called, was excitingly, scandalously, badass, and so were his admirers—the “avant-garde intelligentsia,”7 as one commentator calls them.

Badassery 2: Thomas Defies Convention by Joining the Dominicans

But Thomas was no Peter the Irishman. An intensely religious youth, he needed more in his life than philosophical categories. He also longed to express and live his faith with the evangelical zeal of Christ’s earliest disciples, and he didn’t see staid monasticism providing him with that opportunity. While studying in Naples, he discovered an excitingly different way of following Christ in the recently formed Dominican Order. He was only eighteen or nineteen years old when he joined it.8

For centuries, the going model for religious life in the Latin West was monasticism. Typically, members of monastic religious communities were shut off from the world by a vow of stability. Most monasteries strove to be economically self-sufficient and were located for the most part in rural areas, far away from the noisy distractions of town and city. The monk’s day revolved around prayer and work: ora et labora, as the Benedictines said.

The Dominican Order, like the one launched around the same time by Francis of Assisi, broke with that tradition, scandalizing conventional ecclesiastics and laypeople alike. Founded in 1216 by Dominic de Guzmán, the Order was a badass challenge to the Latin West’s established Christian culture.

At the beginning of the century, Guzmán had been part of a delegation sent to southern France to deal with the so-called Albigensian heresy, a movement that sought to recapture the ardor and simplicity of the primitive Church. Guzmán discovered that he was sympathetic to the Albigensian ideal, and incorporated many of its principles when he founded his Order.

Instead of remaining behind monastery walls, for example, his Dominican brothers would preach to the world, traveling (always by foot) the highways and byways of Christendom to revive and strengthen faith. Rather than belonging to self-sufficient communities that risked falling into commercial frames of mind, Dominicans would be mendicants, practitioners of gospel poverty, relying on the generosity of others for their daily bread. Because they sustained themselves by begging, Dominicans tended to favor urban rather than rural settings. Finally, under Guzmán’s direction, Dominicans put a high premium on both biblical and theological study and on sharing their learning with others.

The Dominicans, in other words, were on fire with love of God and the simplicity of the early Church. They were far removed from the quiet, rhythmic, and cloistered monastic ethos for which young Thomas had been groomed. Everything about them suited him just fine.

Knowing that his parents disapproved of the Dominicans—most respectable people couldn’t get past their mendicancy—he joined the Order without informing them beforehand, much less asking their permission. When they discovered what he’d done, they were predictably horrified. His mother Theodora immediately traveled from the family castle in central Italy down to Naples to rescue her son from his folly. When she got nowhere, she dispatched his brothers to kidnap him and drag him back home. The family’s hope was he would come to his senses if they could just get him away from those damn Dominican dogs who’d brainwashed him.9 Then he could return to Monte Cassino and the respectable ecclesial life his parents had planned for him.

For the next few months, Thomas seems to have been under a kind of house arrest intended to break his spirit. Tradition has it that his exasperated brothers unsuccessfully tried on several occasions to rip the distinctively white Dominican gown off him. Theodora, it must be supposed, frequently pled with him to abandon the Order. Out of what must’ve been sheer desperation, the brothers even paid a prostitute to seduce Thomas in the hope that a quick romp would turn his mind to more worldly pleasures. But we’re told that Thomas seized a blazing log from the fireplace, chased the hapless lass out of his room, and then used the log’s charred end to smudge a huge protective cross on the door. This determined youth defied them all, and did so with admirable brio.10 A real badass.

Finally, in the summer of 1245, Thomas made his escape. Some sources say that he lowered himself on a rope from the tower in which he was held. More likely but less dramatically, Theodora, sensing that her son was determined to remain in the Dominicans, simply gave up and let him go. At any rate, Thomas made his way to the Dominican House at the University of Paris, at the time the absolutely best place in all Europe to study philosophy and theology.

Badassery 3: Thomas’ Grant Synthesis

As a student at the University of Paris, Thomas had the good fortune to study under Albertus Magnus, a genuine thirteenth-century polymath. Recognizing the young man’s genius, Albertus took Thomas under his wing, defended him against his critics, and promoted his rise in academia. The older man’s protection was valuable, because when Thomas arrived at the university, a fierce conflict, part ideological and part turf-protection, was being fought between the secular faculty and the Dominicans, whom the establishment viewed as disreputable upstarts.

Before landing in Paris, Thomas had spent ten years at Monte Cassino and another four in Naples. But from now on, his life would be peripatetic, going wherever his Dominican superiors sent him. He was constantly on the move—Cologne, Rome, Viterbo, Orvieto, eventually back to Paris and Naples—seldom staying longer than two years in any one place.

During these years of studying, teaching, and writing, Thomas perfected his theological approach, one that combined the evangelical zeal that drew him to the Dominicans on the one hand and his deep but not slavish intellectual admiration of Aristotle on the other. Thomas’ great achievement was envisioning and articulating a synthesis of the two: conveying the deep spirituality and humility of his faith with a rigorous defense of what today we call natural theology. It was an astounding accomplishment, a badass fait accompli in which Thomas defended the traditional doctrines of the Church while showing that Aristotelian reason nicely complemented rather than contradicted the tenets of faith.

Thomas the thinker’s modus operandi, especially in the Summa Theologiae, owed much to the disputatio tradition he’d learned as a student. He was unsurpassed in strongmanning, instead of strawmanning, the positions with which he disagreed. The only way truth could be arrived at, he knew, was to be scrupulously fair in one’s examination and assessment of opposing perspectives, an intuition born of evangelical humility and reenforced by the study of Aristotle’s logic. As Thomas memorably writes when commenting on Aristotle’s Metaphysics,

“In choosing or rejecting opinions […] a person should not be influenced either by a liking or dislike for the one introducing the opinion, but rather by the certainty of truth […] [W]e must respect both parties, namely, those whose opinion we follow, and those whose opinion we reject. For both have diligently sought the truth and have aided us in this matter. Yet we must be persuaded by the more certain, i.e., we must follow the opinion of those who have attained the truth with greater certitude.”11

But Thomas the thinker never for a moment supposed that human reason could ultimately penetrate the mysterious essence of God. In keeping with his Aristotelian from-the-ground-up approach, he argued that our senses and reason can tell us that God is, but only faith reveals what God is—and even then, given the finitude of our minds, we can never do much more, as Thomas warns at the very beginning of the Summa Theologiae (I.3.pr), than know what God is not. Divine essence remains hidden from us. (I.1.7.ad1) So, Thomas the Christian insists, charity, hope, and trust, sprinkled with a good dose of humility, must also be brought to the table.12

Given the thirteenth-century clash between the old monastic way of theologizing and the advent of Aristotelianism, it would’ve been so easy for Thomas to have slid into an comfortable fideism that ignored Aristotle, or an uncritical acceptance of Aristotle that sidelined faith (the position apparently taken by his old tutor Peter the Irishman), or a two-truthed model that separated reason and faith into separate compartments, each with its own kind of truth (a position taken by the so-called Latin Averroists of Thomas’ day). But Thomas chose the edgy path—the courageously innovative one—of working out a synthesis that honored both faith and reason.

Just three years after his death, several of his positions would be formally condemned by a Church still too theologically timid to appreciate his badassery.13

Badassery 4: Going Silent

Anyone who knows anything about Thomas has heard this story. Four months before his death, while celebrating Mass on 6 December 1273, he experienced a vision at the altar that led him to stop writing, even though his masterpiece, the Summa, wasn’t yet finished. When his amanuensis Reginald tried to persuade him to resume work, Thomas responded: “Reginald, I cannot, because all I have written seems like straw to me.”14

To my mind, this decision is the finale to Thomas’ life as a badass. He walks away from a work to which he’d devoted the last decade of his life, and by all accounts he does so perfectly serenely. There’s no egoistic hand-wringing at leaving the Summa incomplete, nor is there any self-pitying whine that the whole thing is no damn good. It is damn good, and he knows it. But he also knows that words can only stretch so far, and his theophanous experience at the altar only solidifies his conviction that after a certain point, when we’ve said all that can be said about God, silence is what both reason and faith call for.

Thomas’ walking away from his life’s work is a supreme act of humility and devotion. It’s the final and greatest act of his embrace of mendicancy. He throws away his books, his thoughts, his words, to present himself before God as a beggar.

And if that kind of devotion isn’t badass, nothing is.

###

Greene’s Juan is clearly inspired by José Sánchez del Río (1913-1928), a Cristero executed during the great Mexican persecution of Catholics because he refused to deny his faith. José’s story is tragic, but the saccharine hagiography in which he’s preserved is as off-putting as the story read by Juan’s mother. Hagiographies tend to be mawkish, but ones about sainted children especially so. I recently was asked to write a booklength biography of Carlo Acutis, a youth who will be canonized shortly as the first “millennial saint.” I declined, in large part because I quickly wearied of plowing through the piles of cloying hagiographic encomia under which he’s been buried.

Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory (London: Penguin, 1971), p. 26.

Ibid. pp. 50, 26.

Just one of many examples of overly-pious Aquinas hagiography: “Before his birth several signs predicted the greatness he was destined to acquire. One day when the Countess Theodora was at the castle of Rocca-Secca, a venerable old hermit called the Good, who lived with some companions upon a neighboring mountain, and who was venerated as a saint, went to her and said: ‘Rejoice ! for you bear in your womb a child, who during his life will spread abroad such a splendor of holiness and learning, that this age will give birth to no one able to be compared with him: you will call him Thomas.’ The pious Countess fell upon her knees at his feet, and imitating her who wasthe Mother of God, said: ‘I am am not worthy of such a son, yet be it done unto me according to the holy will of God.’” The Life of the Angelic Doctor St. Thomas Aquinas, by a Father [Pius Cavanaugh] of the Same Order (New York: P.J. Kenedy and Sons, 1881), pp. 3-4. This story has been around a long time. An earlier version of it was used as entered into the record during Thomas’ 1319 canonization process.

Thomas’ occasional bare-knuckled approach is particularly obvious in the polemical essays he wrote against Averroists and critics of mendicant orders. Marie-Dominique Chunu, O.P., offers a good summary of them in his Toward Understanding Saint Thomas, trans. A.-M. Landry, O.P. and D. Hughes, O.P. (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1963), pp. 337-345.

Josef Pieper, Guide to Thomas Aquinas, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991), p. 39.

Ibid., p. 71.

Biographer James A. Weisheipl, O.P., dates Thomas’ entry into the Dominicans in April 1244. See his Friar Thomas D’Aquino: His Life, Thought and Works (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974), p. 27

Dominicans became known as the “dogs of God.” There are at least two accounts of the nickname’s origin. One is that it’s a pun on the name Dominicanus —> domini canis, or dog of God. The other is that Dominic’s mother dreamt, while pregnant with him, of a dog carrying a flaming torch in its mouth that set the world afire.

In his magisterial biography, Weisheipl points out (pp. 33-34) that the story of the prostitute has been disputed by at least two scholars. But it shows up so frequently in the hagiographical record that there’s likely some truth to it.

Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on the Metaphysics of Aristotle. Vol. II. Trans. John P. Rowan (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1961), Book 12, Lesson 9, p. 508. In one of his polemical essays, the 1263 Against the Errors of the Greeks, Thomas defends what he calls the principle of “benevolent interpretation,” basically the suggestion that we should always give interlocutors, especially those with whom we disagree, the benefit of the doubt when it comes to their motives and expertise.

Another manifestation of Thomas’ deep faith are the hymns he composed, most notably the exquisite “Pange Lingua.”

For a brief but informative discussion of the condemnation, see Raphael Comeau, O.P., “The Condemnation of St. Thomas.” Dominicana XXVII/2 (Summer 1942): 93-97.

James A. Weisheipl, O.P., Friar Thomas D’Aquino, p. 321.

Saints as badasses. I agree.