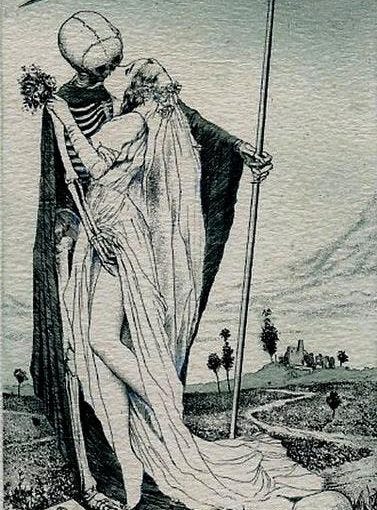

Freud famously argued for the existence of a death instinct: an ever-present psycho-biological pull towards dissolution and destruction that manifests itself in reckless aggressiveness or, less dramatically, in voyeuristic rubbernecking. This fundamental drive, which the Austrian-born Graecophile dubbed Thanatos (Death), is in continuous tension with Eros (Love/Life), the equally foundational drive towards vitality, life, reproduction, and creativity.1

We hardly need Freud to tell us this, do we? Who hasn’t felt the internal push-pull of these two instincts? Part of us yearns for life-enhancing activities and relationships and is repelled by violence and the threat of death. Yet another, perhaps more chthonic part is moth-attracted to the glare of self- and other-destructive behavior. It’s as if each of us has a Thanatos-Eros set of pistons in our spiritual engine blocks. Sometimes life-affirming Eros is in the ascendency, driving down Thanatos, but sometimes, as bitter personal and cultural experience tells us, the death-craving Thanatos goes full throttle.

The ancients were as aware of this inner civil war as we are today. It’s a major Homeric theme as well as the dark thread that runs through Greek tragedy. Nor does it escape the notice of the philosophers. Plato gestures at it twice in the Republic, his longest dialogue.2

Troglodytes, Light-Seekers

In Book VII of the Republic, we’re offered one of the most famous tales in the history of philosophy. It’s about a race of troglodytes or cave dwellers who are born, live, and die in subterranean darkness illumined only by a fire which casts shadows on the cave walls. Because they’ve never experienced anything else, the troglodytes take the shadows for substance. They mistake appearance for reality.

One happy day, a restless cave dweller stumbles his way to the surface of the earth and for the first time, in the pellucid light of day, beholds the real world. Seeing things as they truly are, he realizes that what he’d always thought were real—cave shadows—were just one-dimensional wraiths.

Overjoyed, he rushes back into the earth’s bowels to tell his fellow troglodyes about his wonderful discovery. But to his surprise, they greet the news with scornful laughter. The more he persists in his wild tale, the more irritated they become. Will this idiot never shut up?! By the end of the tale, they’re so sick of him that they actually want to kill him.3

Now, Plato intends this as a rather transparent allegory. The troglodytes are stand-ins for people who refuse to relinquish their illusions, even when the facts are presented to them. Instead, they cling ever tighter to their falsehoods and deride if not outright persecute anyone who dares challenge them. They prefer to remain in the darkness where all their sacred cows graze.4

This kind of willful ignorance is surely a child of Thanatos. It prefers the deadness, the corruption, the dark stupidity of falsehood to the living and illuminative vitality of truth.

But Plato’s allegory isn’t totally pessimistic. Eros is present in it too. Troglodytish obduracy doesn’t quite rule the day. After all, one of the cave dwellers makes his way to the surface. Perhaps even without being able to articulate his motive, he hungers for life and light. It’s not unreasonable to presume that his description of what he encounters just might awaken in some of the other cave dwellers a similar longing for life-bestowing truth.

Even in the darkness there’s the promise of light, just as the light is always threatened by darkness. One piston moves up and the other moves down.

Wretched Eyes, Disciplined Eyes

Plato’s other allusion in the Republic to the interior tug-of-war comes in Book IV. It concerns one Leontius, who on his walk one day saw the publicly displayed rotting corpses of executed prisoners.

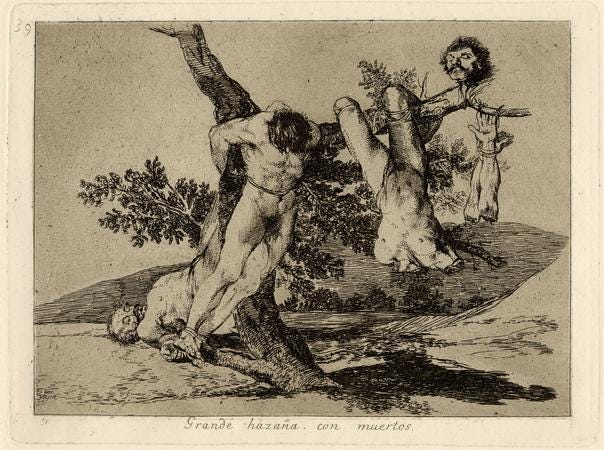

He desired to look, but at the same time he was disgusted and made himself turn away; and for a while he struggled and covered his face. But finally, overpowered by the desire, he opened his eyes wide, ran toward the corpses and said: “Look you damned wretches, take your fill of the fair sight!”5

My guess is that Leontius didn’t just happen to pass by this gruesome scene. The Thanatos attraction to death and decay prodded him in its direction. His Eros drive fought it, but was eventually overpowered—feast yourselves, you damn eyes!—and yet not extinguished. The troglodyte within leers at the carrion, but the part of Leontius which has clawed itself out of the shadowy cave is disgusted at succumbing to the dark craving for death.

Intellect & Will

Between them, these two illustrations of the Thanatos-Eros dynamic are far-reaching. One focuses specifically on reason or intellect and the other on will.

The allegory of the cave warns us of what happens if we allow the troglodyte of ignorance and bigotry to overwhelm reason. Individuals as well as entire cultures can succumb to a death-dealing refusal to accept reality as it is, clinging instead to insubstantial and destructive falsehoods. The glare of truth is blindingly painful to those who prefer the cave’s protective shroud of darkness.

Leontius’ example cautions against what can happen when the will succumbs to lurid passion. Unlike in the cave allegory, reason or intellect isn’t compromised here. Leontius knows the better but chooses the worse, despite his awareness that his choice is corrosive of his character. The Thanatos piston of undisciplined passion ascends, the Eros one of thoughtful moderation descends.

But still, the cave entrance is an option, as is taking the path that doesn’t pass by gallows hill. That’s because Freud claims that these two drives—love/life and death, reason and passion, desire for truth and willful ignorance—are always in relationship with one another. Sometimes they achieve balance: the pistons are neck-to-neck. But stasis never lasts long. It inevitably gives way to personal spurts or cultural periods of intense creativity, or personal spurts or cultural periods of dreadful destructiveness.

At least until now. But in our time of global warming, growing illiteracy, political rancor, personal incivility and social ennui, cultural violence, economic disparity, and the threat of widening armed conflict, it’s hard not to suspect that the Thanatos piston is in the ascendency, and that it just might’ve gotten stuck to the point of no return. Perhaps the cultural engine block has seized up, ushering in a dark age of troglodytes and wretched eyes.

###

Freud explores his distinction between Thanatos and Eros in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) and Civilization and Its Discontents (1930).

But allusions to it crop up in lots of Plato’s dialogues, particularly the early ones in which we see the folks who engage with Socrates clinging to delusion and falsehood instead of going where the elenchus properly ought to take them.

Republic, 514a-517a.

I’m punning here, rather badly, on Hegel’s notorious criticism of Schelling’s Absolute, the obscurity of which Hegel compared to a “dark night in which all cows are black.”

Republic, 440a. I’m using Harold Bloom’s translation.

Is the timeless tension you cite, Kerry, from at least a Freudian perspective, not also associated with what we now commonly call “bipolar disorder”?

Or, in earlier language, Nietzsche’s hot Dionysian ascendant elation, followed by comparatively cold Apollonian descendent repose?

You’re onto something here, doubtless, Kerry. But where does that leave humanity’s persistent sense of hope? A mete cryptic human illusion, as the ancients ironically warned?

Thanatos, and his close brother, Sleep, is hopefully more than a final escape from the normal struggles of human life.

Eros has its place, surely, if not in completely defeating Thanatos. Then at least in fostering the joie de vivre we all appreciate, however rare and unpredictable that mellow state is.

Let us not be too dark and forlorn in all this, I suggest. The escaping, sun-awed cave-dweller, on my read, is finally joyous -- assuming he manages to escape assassination by his confused, ignorant, threatened peers. In other words, there is hope for humanity even now.