“Revenge is a kind of wild justice; which the more man’s nature runs to, the more ought law to weed it out. For as for the first wrong, it doth but offend the law; but the revenge of that wrong putteth the law out of office.” —Francis Bacon1

“Shakespeare holds up to his readers a faithful mirror of manners and of life.” —Samuel Johnson2

A presidential candidate announces “I don’t get too angry; I get even,” and promises his aggrieved supporters that he will be their “retribution.”3 A North Carolina gubernatorial candidate stands at a church pulpit and, while disingenuously denying that he’s promoting vengeance, thunders “some folks need killing! It’s time for somebody to say it. It’s not a matter of being mean or spiteful. It’s a matter of necessity!”4 And in recent years, several reputable scholars have defended vengeance as a morally acceptable—and even salutary—response to perceived wrongs.5

Condemned for centuries as a vice, revenge or vengeance6—what Lord Bacon famously called “wild justice”—is staging a comeback. An increasing number of us see nothing untoward about “getting even” with someone we think has injured us—and doing so “in spades,” as the saying has it. We dwell, as one commentator puts it, in a “culture of vengeance,” even if we still feel uncomfortable enough with the word to replace it with euphemisms like “defending rights,” “defeating evil,” or (per the ex-president and gubernatorial hopeful), “retribution” and “a matter of necessity.”7

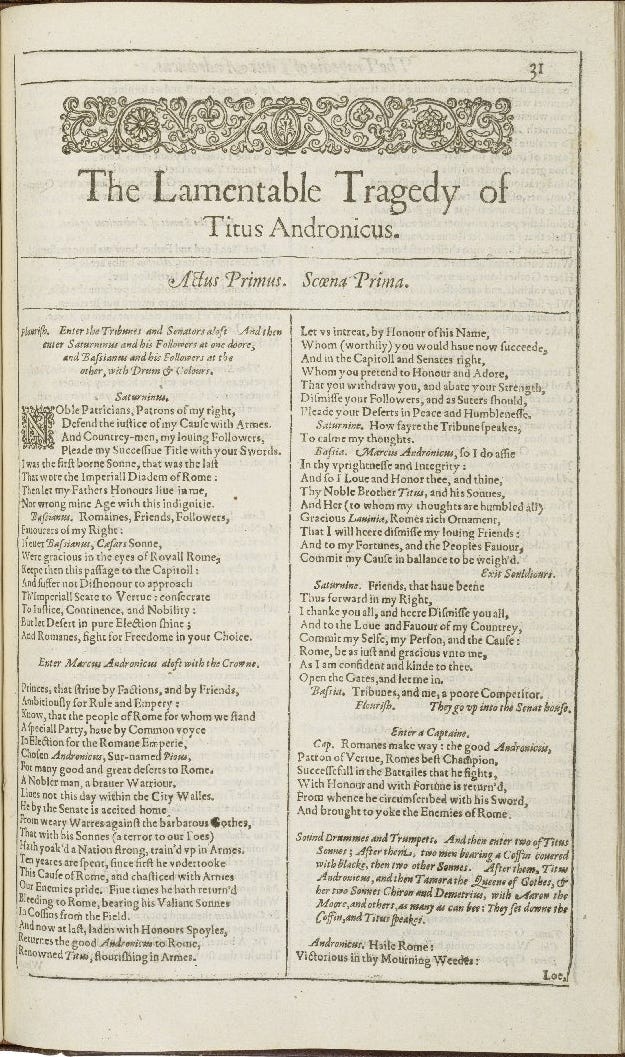

One of the most striking literary warnings against viewing vengeance as anything less than a destructive passion is Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus. The Bard often explores ethical dualities in his plays: love and greed in King Lear, nobility and arrogance in Coriolanus, generosity and parsimony in Timon of Athens, jealousy and trust in Othello, and so on.8 In Titus, Shakespeare focuses on the clash between vengeance or wild justice and the rule of law. In tracing the fate of the Andronici family, he grippingly—and at times horrifyingly—shows how the lust for vengeance destroys both those who wield it and those who receive it, and how fidelity to law forestalls such chaos.

But Shakespeare is too perceptive a student of human behavior to present his case in unimaginative polarities. In Titus, he acknowledges that even people who respect the law can convince themselves and others that under certain circumstances vengeance is a vehicle for good. The play invites us, in other words, to ask ourselves this question: destructive as it is, might Bacon’s “wild justice” sometimes be the only option? Or is this a self-serving delusion?

An “Aberrant, Barbarous Work”?9

In general, Titus hasn’t fared well with Shakespeare aficionados and scholars. They find it off-puttingly sanguinary and stylistically clunky. Mark Van Doren and Harold Bloom, for example, deem it so awful that they can only conclude Shakespeare must’ve been parodizing blood-soaked revenge plays like Marlowe’s Jew of Malta and Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy that so besotted Elizabethan audiences.10 Harold Goddard speaks for those less charitable but more numerous critics who dismissively insist that the “piled-up cruelties and brutalities” in Titus “follow one another with such crudity and rapidity that it produces no conviction of reality.”11

There may be some merit to these objections. Since the play is one of Shakespeare’s earliest (1593-94), it might be that he was still learning his craft. Or perhaps he deliberately catered to the popular taste for revenge plays in order to maximize profits. (If so, he succeeded. Ben Johnson intimates in the “Induction” to his Bartholomew Fair that Titus was a blockbuster.12) Or, as Bloom and Van Doren suggest, maybe he was just having some fun at the expense of his dramatic rivals (both of whom, by the way, died the year Titus was likely written).

It’s certainly the case that Titus is over-the-top when it comes to bloody mayhem. In a 2014 run of the play at the Globe, a theater critic for The Independent fainted. In fact, “more than 100 people either fainted or left the theater after being overcome by on-stage core.”13 And even though there’s some fine poetry in the play, it never rises to the genius of the later tragedies. Still, Titus deserves better than it’s generally gotten. As the always insightful Shakespeare scholar Marjorie Garber says, Titus, for all its faults, is “an extraordinarily powerful story.”14

It’s powerful because its theme—the shockingly fluid way vengeance spirals into destructive chaos—is a perennially timely moral warning. The vengeful refusal to forgive past grievances inevitably spawns discord. Encouraging an ever escalating and ever deadlier vendetta-style series of retribution, revenge disdains discrimination and proportionality, hallmarks of law. Innocent and guilty alike are fair game, and the goal is always to inflict more retaliatory harm than was suffered. The stakes keep rising.

One way for a dramatist to drive home the savagery of vengeance is to personify it in an on-stage bloodbath. That’s precisely what Shakespeare does in Titus. The play is brutal because vengeance is brutal. Its choreographed gore can be interpreted as a inexperienced dramatist’s clumsy strategy for eliciting shock. But I think it more likely that the play’s horrific mayhem is deliberately over-the-top to impress upon the audience the horrific consequences of bypassing law in pursuit of revenge. Neither the play’s contrived nor the realworld effects of vengeance are for the squeamish. But it’s good to be reminded of them and to be forewarned.

“A wilderness of tigers”

The play takes place at some unspecified date in the late Roman Empire. Unlike Shakespeare’s other Roman plays, Titus features no characters taken from the historical record. All are the Bard’s creations.

Titus Andronicus, a seasoned and respected general, returns to Rome after a victorious campaign against the Goths. He brings as captives Tamora, their queen, along with three of her sons. Ignoring Tamora’s plea for leniency—“And if thy sons were ever dear to thee, / O think my son to be as dear to me… / Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge” (I.i.107-08, 119)—Titus has Alarbas, the eldest of the three, cruelly butchered in an extra-legal act of vengeance, thereby setting in motion the cycle of retaliation.

Titus’ act is especially shocking because he sees himself as an unswervingly moral man, a “patron of virtue.” (I.i.65) His entire military career has been in the service of a Rome which, in his mind, brings to the world discipline, order, and respect for law. That’s why he’s devoted his life to fighting the barbarian threat to the empire’s stability.15 But in slaughtering Tamora’s son, Titus reveals a darkness that runs counter to his public fidelity to order. He shows himself willing to bypass the law when it suits his purpose. As we’ll shortly see, this is a predictable move of someone seeking revenge.

Following the execution of her son, Tamora rather improbably segues from captive to consort of the Roman emperor Saturninus. She immediately uses her new status to retaliate against Titus. She is resolved to be “consecrate[d]” to “villainy and vengeance.” (II.i.28) Since Titus killed one of her sons, she’ll go after his children. But there’s no proportionality to her scheme, no straightforward eye-for-an-eye isomorphism—another characteristic of the revenge-seeker. She wants to destroy all of Titus’ children. “N’er let my heart know mercy cheer indeed,” she vows, “Till all the Andronici be made away.” (II.iii.189-90) The stakes have gotten higher.

Lavinia, Titus’ daughter, is married to Bassianus, the emperor’s brother. With the aid of her on-the-side lover, Aaron the Moor—“vengeance in my heart, death in my hand,” he says of himself (II.iii.48)—Tamora encourages her two remaining sons, Demetrius and Chiron, to slay Bassianus and frame Titus’ sons for the murder. “Revenge it as you love your mother’s life,” she enjoins them, “Or be you not henceforth called my children.” (II.iii.114-15) Thus she implicates the next generation in her vendetta, ensuring (she hopes) that the retaliation will continue for as long as it takes to wipe out the Andronici.

Vengeance won’t let past grievances fade into forgetfulness or die. It drags the moldering memory of them into the present and hurls them into the future. This is metaphorically (and nightmarishly) alluded to when Aaron the Moor boastfully recounts the history of his wickedness.

“Oft have I digged up dead men from their graves

And set them upright at their dear friends’ door,

Even when their sorrows almost was forgot,

And on their skins, as on the bark of trees,

Have with my knife carved in Roman letters

‘Let not your sorrow die, though I am dead.’” (V.iii.137-42)

Tamora does more than encourage her sons to murder Bassianus. Revoltingly, she also urges them to rape his wife Lavinia—a shocking retaliatory escalation.

Remember, boys, I poured forth tears in vain

To save your brother from the sacrifice,

But fierce Andronicus would not relent.

Therefore away with her, and use her as you will;

The worse to her, the better loved of me. (II.iii.163-67)

But Tamora’s sons do more than rape poor Lavinia; they also chop off her hands and rip out her tongue to prevent her from identifying them. Mercifully, Shakespeare has this atrocity occur off-stage. But the scene in which Lavinia re-appears, maimed, bloodied, and cruelly mocked by Demetrius and Chiron, is a perpetual shocker. It’s the one that caused the audience meltdown in the play’s 2014 Globe production.

Demetrius (to Lavinia):

“So, now go tell, an if thy tongue can speak,

Who ‘twas that cut thy tongue and ravished thee.”

Chiron:

“Write down thy mind, bewray thy meaning so,

An if thy stumps will let thee play the scribe.

…An ‘twere my cause, I should go hang myself.”

Demetrius:

“If thou hadst hands to help thee knit the cord.” (II.IV.1-4, 9-10)

Saturninus, deceived by Tamora into believing that Titus’ two sons are Bassianus’ murderers, orders them arrested. A distraught Titus pleads for their lives. The pendulum has swung; he’s exchanged places with Tamora, who once pled for her son. Aaron the Moor tricks Titus into thinking that Saturninus will pardon the two boys if Titus cuts off one of his own hands, which he, in his desperation, does. But shortly afterwards, Saturninus returns to Titus both the severed hand and the heads of his two sons. More bodies, more victims, devoured by rapacious vengeance.

“Bodies” is exactly the right word here. A corpse, a dead body, is a thing, an object, a less-than-person. The lust for vengeance—first Titus on Tamora’s son, then Tamora on Titus’ son-in-law and daughter, then Saturninus’ on Titus’ two sons —leads to nothing but bodies. And even though poor Lavinia yet lives, her maiming reduces her, too, to a kind of thinghood. When his tongueless and handless child is first presented to Titus, her uncle Marcus, stunned at the sight, blurts out, “This was thy daughter.” Note the significant past tense. On seeing her, Lavinia’s horrified brother Lucius exclaims, “Ay me, this object kills me!” (III.i.64, 66): this “object,” this thing that was once a vibrant sibling but is now stripped of the quintessential human abilities to communicate and create, this less-than-person.

Shakespeare’s reduction of living persons to bodies or thinghood dramatizes (or, some might say, melodramatizes) the dehumanizing effects of vengeance. Its targets are no longer viewed as subjectivities worthy of moral consideration; instead, they become opague pawns in a retaliatory game of ever higher stakes. But the reduction also suggests another consequence of revenge-seeking: fragmentation. Shakespeare’s stage becomes a virtual abbatoir of dismembered body parts: Tamora’s son’s limbs are hewed (I.i.97), Bassianus is hacked to death (II.iii.19), Lavinia’s tongue and hands are severed (II.iv.1), Titus loses a hand (III.i.193), and his two unfortunate sons their heads (III.i.239). To underline the nightmarish disjointedness, Titus’ severed hand is at one point thrust into Lavinia’s speechless mouth. (III.1i.287)

The point is obvious: vengeance not only fragments its human victims’ bodies, but also the body politic, which under normal circumstances is held together by the rule of law. When vengeance takes hold, it’s not simply that things fall apart; strange and unnatural alliances (Titus’ hand in Lavinia’s mouth) are also formed. Vendettas create toxically broken environments in which each faction is against all in a no-holds-barred vendetta that mocks order. In such a climate, as Thomas Hobbes famously insisted, “every man is enemy to every man”16—or, in the case of Titus, every clan is enemy to every clan, spawning a “wilderness of tigers.” (II.i.54)

“Terras Astraea reliquit!”

Social and political fragmentation erupts when law is ignored. Ideally (although, obviously, not always practically) law functions to maintain social order and cohesiveness through an impartial and rational application of rules, principles, and precedents when disputes between people arise. At the beginning of the play, this ideal is voiced by Marcus: “Suum cuique” he says, “is our Roman justice.” (I.i.283) “To each his own”: the law seeks to treat people fairly, determing through a judicial examination of evidence what’s theirs and what isn’t, what they’re owed and what they owe others.

Suum cuique may’ve once been the hallmark of the Roman state, but Marcus is naive to think it remains so. Titus knows better. Driven nearly mad by the savagery of his feud with Tamora, he shrieks (IV.iii.4), “Terras Astraea reliquit!”: “Astraea, the goddess of justice, has left the earth!” The irony, of course, is that it’s Titus himself who precipitated Astraea’s flight with his vengeful slaughter of Tamora’s son.

Astraea is often depicted as blindfolded to stress that justice plays no favorites. The rule of law ideally is unmixed in motive, its only goal being to ascertain the truth. It intends no harm to anyone but transgressors. It conducts its business in public, not in secrecy.17

Vengeance, on the other hand, always operates from a cacophony of mixed motives: personal grievance, outrage, jealousy, spite, and so on. No blindfold for vengeance: it deliberately targets individuals for retaliation, and is more than willing to harm innocent people as part of its one-upmanship payback. Unlike the law, it prefers to act behind the scenes so as to maximize the shock of its retaliation: vengeance, as they say, is a dish best served cold—that is, unexpectedly.

In reflecting on the difference between law and revenge, Thomas Aquinas argued that the nonvengeful person, when harmed by another, is properly motivated by bona ira or “righteous anger” that seeks redress within the boundaries of the law. But the person prone to revenge-seeking operates from mala ira, “evil or sinful wrath,” and uses it as a license to resort to extra-legal violence that, as we’ve seen, leads to dehumanization, fragmentation, and social chaos.18 As Francis Bacon warned, revenge or wild justice “putteth the law out of office.”

The rule of law seeks to restore ruptured social harmony; as we’ve seen, extra-legal vengeance couldn’t care less about preserving social harmony. All it wants is to get its own back, regardless of how much damage it inflicts on uninvolved others in the process. This is because the person of revenge takes himself to be the exclusive source of law; whatever he decides to do—slay, rape, mutilate—is right and proper, just so long as it harms his adversary. He is a free agent.

Another way of putting this is to say that he has declared himself literally “autonomous.” The word means “self-lawed” (autos = self; nomos = law). But the respecter of law, the person who seeks adjudication rather than vengeance, is heteronomous (hetero = other, another). She recognizes that both personal and social stability rest on a regard for the well-being of others, and that this in turn depends on respect for objective boundaries neither contrived nor legitimately ignored by her own will. Titus’ forlorn appeal to the goddess of justice suggests that some boundaries are ultimate and absolutely non-negotiable. Some law is theonomic (theos = god), divinely established.

In the spiral of vengeance that sweeps him up—and which, recall, he inaugurated—Titus moves from heteronomy and theonomy to autonomy. Since there is no longer law in tiger-ridden Rome, he will make himself the final arbiter of right and wrong. This is, of course, the self-delusion that allows for the ever-increasing escalation of retaliation and counter-retaliation characteristic of vengeance. As Titus says in the presence of maimed Lavinia,

“Let us that have our tongues

Plot some device of further misery

To make us wondered at in time to come.” (III.1.135-137)

But Lavinia, de-personed though she seems to be, instantly recognizes the folly of Titus’ burning lust for vengeance. Lucius notices that upon hearing her father’s words, his “wretched sister sobs and weeps.” (III.ii.139) Her literally unspeakable trauma has given her the foresight of a Cassandra. Titus, however, will have his revenge.

“I shall never come to bliss

Till all these mischiefs be returned again

Even in their throats that hath committed them.” (III.i.277-79)

Since there is no longer justice on earth—the goddess has fled—Titus must make his own justice: wild justice. It’s hard not to sympathetize with his frustrated outrage, the “gnawing vulture of th[e] mind” (V.ii.32), even if the way in which he ultimately satisfies it is deplorable. But in a society where the rule of law has been either demolished or compromised, how else is one to find fairness—suum cuique—than by seizing it?

The Bottomless Passion

Once Titus has declared himself a law unto himself, he dedicates his energies to avenging his daughter and sons with a ferocity that so frightens his brother Marcus that he seeks to rein him in.

Titus

“Is not my sorrow deep, having no bottom?

Then be my passions bottomless with them.”

Marcus

“But yet let reason govern thy lament.”

Titus

“If there were reason for these miseries,

Then into limits could I bind my woes.

When heaven doth weep, doth not the earth o’erflow?

If the winds rage, doth not the sea wax mad,

Threat’ning the welkin with his big swoll’n face?

I am the sea…, I the earth.” (III.i.221-28, 230, 231)

He will not allow reason to dilute his fury nor will he rest—

“Look you eat no more

Than will preserve just so much strength in us

As will revenge these bitter woes of ours” (III.ii.1-3)

—until he is avenged.

Titus learns the names of Lavinia’s assailants and Bassianus’ murderers when she manages to scratch their names in the sand by manipulating a stick with her mouth and feet. In quick order, Titus lures the culprits to his home. Before butchering Demetrius and Chiron as if they were food animals—which in fact, they are about to become—he tauntingly outlines for them his programme of vengeance.

“Hark, wretches, how I mean to martyr you.

This one hand yet is left to cut your throats,

Whiles that Lavinia ‘tween her stumps doth hold

The basin that receives your guilty blood.

You know your mother means to feast with me …

Hark, villains, I will grind your bones to dust,

And with your bond and it I’ll make a paste,

And of the paste a coffin I will rear.

And make two pasties of your shameful heads,

And bid that strumpet, your unhallowed dam,

Like to the earth swallow her own increase.

This is the feast that I have bid her to,

And this the banquet she shall surfeit on. (V.ii.184-188, 190-197)19

The climax of the revenge cycle occurs at the banquet where Titus’ nightmarish dish is served to Tamora and Saturninus. Dressed as a cook and accompanied by Lucius and Lavinia, he waits until his victims have stuffed themselves with the unholy pie he prepared for them. Then, as an act of mercy (but also vengeance? “See what you’ve made me do to my own daughter?”) Titus horrifies his guests by slaying Lavinia before their eyes: “Die, die, Lavinia, and thy shame with thee, / And with thy shame thy father’s sorrow die.” (V.iii. 46-47)

When a shocked Saturninus shouts, “What hast thou done, unnatural and unkind?” (V.iii.48), Titus responds that Democritus and Chiron had already slain his daughter—turned her into a less-than-person—by raping and maiming her. Saturninus demands that the two culprits be delivered to him at once. This is the coup de grâce moment Titus has been waiting for.

“Why, there they are, both baked in this pie,

Whereof their mother daintily had fed,

Eating the flesh that she herself hath bred.” (V.iii.61-63)

“‘Tis true, ‘tis true,” he triumphantly chortles, clearly in response to the horrified, revulsion on Tamora’s face. Then follows an almost orgiastic flurry of deaths: Titus stabs Tamora, Saturninus kills Titus, and Lucius kills Saturninus. The banquet hall becomes an ensanguined shrine to Bacon’s wild justice. A curse spat out by Aaron the Moor earlier in the play—“Vengeance rot you all!” (V.i.59)—has come to pass.

“To knit again”

The orgy of death puts an end to the primary players in Titus’ cycle of vengeance. Lucius, upon slaying Saturninus, proclaims its finish: “There’s meed for meed, death for a deadly deed.” (V.iii.67) It’s over; recompense-for-recompense, eye-for-an-eye. No more stretching beyond boundaries. Proportionality is restored.

Lucius seems to be suggesting that the simplest kind of justice has been meted out, even though the agent of its delivery was, paradoxically, vengeance. Speaking to the shocked crowd, the “sad-faced men, people and sons of Rome” (V.iii.68) who gather as news of the banquet massacre leaks out, Lucius recounts for them the entire history of the feud in an attempt to justify the truly horrifying actions his desperate father Titus took to redress “wrongs unspeakable, past patience.” (V.iii.127) Significantly, though, he assures them that the cycle of violent retribution ends even if their judgment goes against him and his uncle Marcus, the only two surviving Andronici. In promising this, Lucius announces his refusal to become a law unto himself. He embraces heteronomy, order, the law. The irony, of course, is that in doing so, he asks the people of Rome to exonerate him and his family, or at least forgive them, for the extra-legal way in which the feud ended.

“Have we done aught amiss? Show us wherein,

And from the place where you behold us pleading,

The poor remainder of Andronici

Will, hand in hand, all headlong hurl ourselves,

And on the ragged stones beat forth our souls,

And make a mutual closure of our house.

Speak, Romans, speak, and if you say we shall,

Lo, hand in hand, Lucius and I will fall.” (V.iii.131-38)

The crowd accepts Lucius’ defense of the wild justice he and his family practiced, even as it’s clear that they’re weary of the chaos it wrought. “By uproars severed as a flight of fowl / Scattered by winds and high tempestuous gusts,” (V.iii.69-70), all the people want now is a return to normalcy, to order, discipline, and respect for law that Rome once stood for. Lucius promises to help them restore the fragmented body politic.

“O, let me teach you how to knit again

This scattered corn into one mutual sheaf,

These broken limbs again into one body.” (V.iii.71-73)

Given the the play’s relentlessly vengeful back-and-forthing between Titus and Tamora, this conclusion seems a bit rushed and anemic. After an entire storyline focused on the utter breakdown of social cohesion, a mere three lines expressing the hope that what was broken can be mended doesn’t exactly inspire confidence.

Perhaps the play’s ending is another example of stylistic clunkiness from Shakespeare the fledgling playwright. But I think he might have concluded Titus Andronicus in this way to impress upon his audience the vulnerability of law and social order when challenged by human ambition, rage, spite, and lust for retribution. Wild justice is humanity’s constant temptation.

That’s why the play still speaks to us today. It reminds us that when presidential nominees promise retribution and draw up an enemies list,20 or when a gubernatorial candidate incites a crowd to kill people with whom they think they have a political beef, or when an ideologue insists that law is a nothing more than a tool of oppression, or even when we hear an average guy or gal spouting off about getting even with someone, we ought to pay attention, lest vengeance rot us all.

###

Francis Bacon, “Of Revenge,” The Works of Francis Bacon, Volume II. Ed. James Spedding, Robert Leslie Ellis and Douglas Denon Heath (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1900), p. 92.

Samuel Johnson, “Preface, 1765,” in Selections from Johnson on Shakespeare, ed. B.H. Bronson with J.M. O’Meara (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986), p. 10.

Lalee Ibssa and Soo Rin Kim, “‘I get even’: Trump targets Haley after she pledges to keep fighting him following 2 losses.” ABC News (24 January 2024); Robert Downen and William Melhado, “Trump vows retribution at Waco rally: ‘I am your warrior, I am your justice’”. Texas Tribune (25 March 2023).

Greg Sargent, “MAGA Gov Candidate’s Ugly, Hateful Rant: ‘Some Folks Need Killing!’”. The New Republic (5 July 2024).

For example, Susan Jacoby, Wild Justice: The Evolution of Revenge (New York: Harper & Row, 1983); Peter A. French, The Virtues of Vengeance (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2001); and Thane Rosenbaum, Payback: The Case for Revenge (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

I use the two synonymously.

Terry K. Alajdem, The Culture of Vengeance and the Fate of American Justice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Shakespeare so often juxtaposes virtue and vice because he sees their duality imbedded in human nature itself. As he says in All’s Well That Ends Well (IV.iii.73-76):

The web of our life is of a mingled yarn,

Good and ill together. Our virtues would be proud

If our faults whipped them not, and our crimes

Would despair if they were not cherished by our virtues.

All quotations from Shakespeare’s plays are from the Folger Shakespeare Library editions.

R. S. White, “Titus Andronicus and Romeo and Juliet,” in Shakespeare: A Bibliographical Guide, ed. Stanley Wells (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 182-83.

Mark Van Doren, Shakespeare (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1939), p. 29; Harold Bloom, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (New York: Riverhead Penguin, 1998), p. 78. In a related but not identical way, Laurie Maguire suggests that Titus may be a parody of metaphor itself rather than of revenge plays. Studying Shakespeare (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), pp. 173-175.

Harold C. Goddard, The Meaning of Shakespeare. Volume 1. (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1951), p. 33. I hasten to add that even though I disagree with Goddard’s evaluation of Titus, I find his two-volume study of Shakespeare generally quite insightful.

Ben Johnson, “The Induction on the Stage,” Bartholomew Fair, ed. Simon Trussler (London: Methuen, 1986), p. 7.

Nick Clark, “Globe Theatre Takes Out 100 Audience Members with Its Gory Titus Andronicus,” The Independent (22 July 2014).

Marjorie Garber, Shakespeare After All (New York: Anchor, 2004), p. 74.

But Titus’ fidelity to the law is harshly rigid. Early on in the play (I.i.297), he slays one of his own sons because of what he takes to be a violation of the law on the youth’s part. His unimaginatively lockstep attitude stems, perhaps, from his military career: an order is an order, a rule is a rule, and extenuating circumstances matter not.

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1929), p. 96.

See Robert Broude, “Four Forms of Vengeance in Titus Andronicus.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 78/4 (October 1979): 494-507).

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae II-II, q. 158. a. 2.

That Shakespeare borrows this almost wholecloth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses tale of Philomel and Procne (to which Titus actually refers [V.iii.98-99]) does nothing to lessen its shock value to audiences of his day and ours.

Edith Olmsted, “Trump Ally Exposed for Horrific Hit List of Political Enemies.” The New Republic (10 July 2024).

GREAT historical and literary analysis, Kerry. Thanks so much.

Regarding the moralistic, ethical, and legal warnings I find two faults. One, the cycle of revenge and violence is nothing new; neither in US political assassinations nor in the world-scene. Perhaps you didn't mean to give that impression, but I thought I read it that way.

Second, moralization is of no consequence. Revenge and violence operate at the atavistic level and "man is (simply) the animal who doesn't beleve it is an animal."