“He that loves to be flattered is worthy o’ th’ flatterer.”1

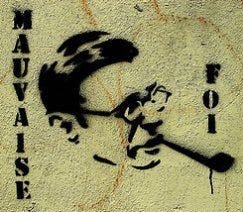

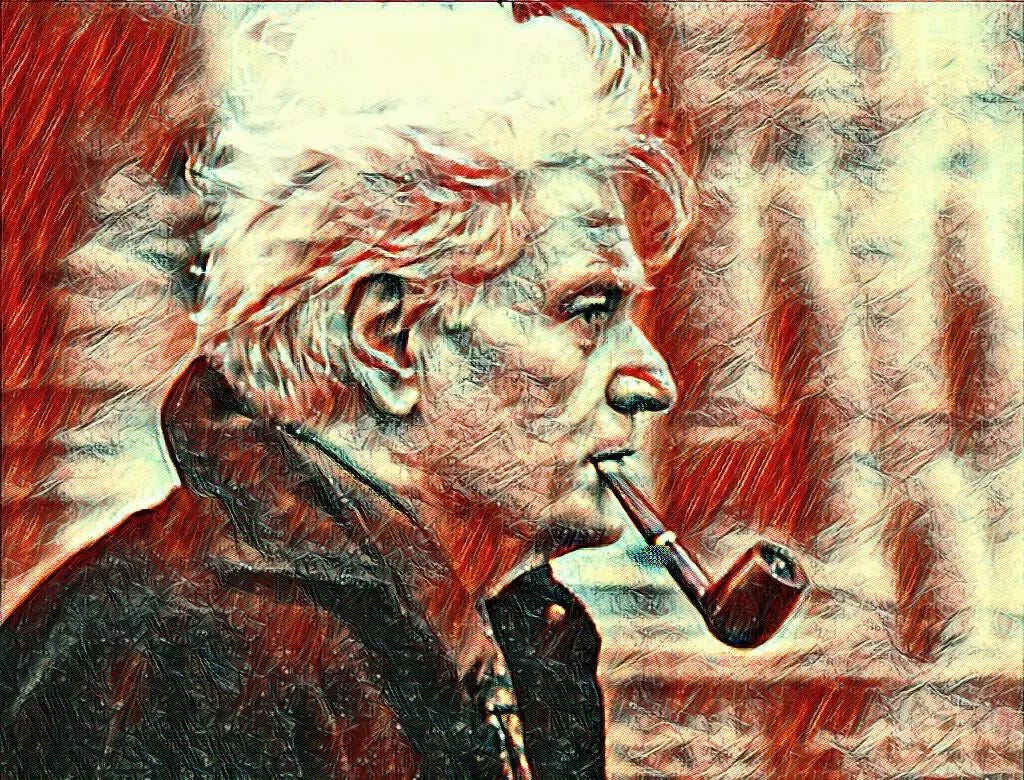

“In bad faith it is from myself that I am concealing the truth.” Jean-Paul Sartre2

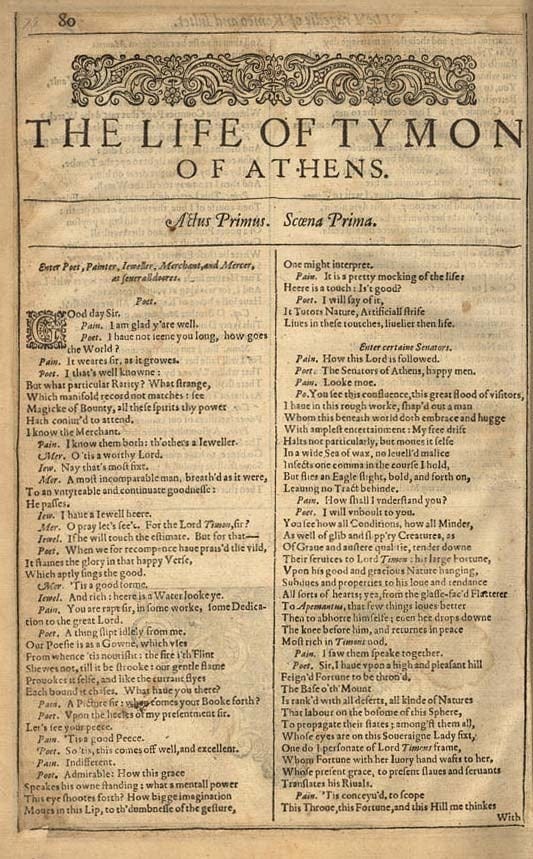

Shakespeare aficionados and scholars alike never have been quite sure what to do with Timon of Athens.3 Most agree that the play was unfinished—one of them actually calls it an “amazing torso”4—that it was probably cowritten with Thomas Middleton, and that it, like Troilus and Cressida, went unstaged during Shakespeare’s lifetime. They also agree that the play is shockingly splenetic,5 so much so that at least two of them6 suggest it might be a literary purgation of Shakespeare’s pent-up frustration with authorities and patrons.7 The poet W. H. Auden doesn’t go that far. But he does think the play’s uneven quality points to the conclusion that Shakespeare was likely “ill or exhausted” when he wrote it.8

That’s about where the agreement ends, however, because there’s no consensus on when the play was written—guesses range between 1601 and 1607—or even to what genre it properly belongs. The majority but by no means unanimous opinion is that it’s probably a tragedy. But critic A.D. Nuttall, unconvinced, throws in the taxonomic towel with a weary “It is the strangest of Shakespeare’s plays.”9 An equally frustrated Harold Bloom settles for saying it falls “somewhere between satire and farce.”10

More importantly, readers and critics are divided when it comes to the play’s message. Some see Timon as a genuinely good and generous man, others as a manipulative hypocrite. Some argue that ingratitude is the play’s primary theme while others argue that money’s corrupting influence takes center stage.

I agree that Timon of Athens is rough around the edges. But I think Shakespeare clearly intended it as tragedy, that it’s foolish to read it as as just a therapeutic exercise in letting off steam, and that despite its incompleteness it contains many lines worthy of the Bard. I’m also convinced that the variety of ways in which the play’s been interpreted is a testament to its depth and complexity, and that they all tie together once one realizes that the play is about a human failing the 20th-century philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre calls “bad faith.” As such, Timon of Athens, like all Shakespeare’s tragedies, speaks resoundingly to us today. Like all of his tragedies, it’s a morality play that invites us to reflect on the state of our own characters.

Timon in Brief

When the play opens, Timon is bestowing incredible gifts of money to a number of people at one of his lavish banquets. None of them are are genuine companions to him, much less friends. They’re hangers-on who flatter him or offer small services because they know that his reponse will be outlandishly disproportionate to what they give: Timon’s over-the-top generosity is legendary. The only character who refuses to play this game is Apemantus, described as a “Cynic philosopher”11 who despises wealth and luxury.

In the midst of the revelry, Flavius, Timon’s steward, tries to warn his master that he’s run through his entire fortune and that creditors are at the door. Timon at first refuses to take the news seriously. But when he finally accepts it, he sends Flavius and other servants to several men who have enjoyed his generosity in the past. Perhaps they’ll loan him the money he needs to keep his creditors at bay. But hey all refuse, and when Timon learns of their hard-heartedness, he denounces them as fairweather friends, forsakes Athens, and retreats to the wild, where he makes a home for himself in a cave. He wants nothing more to do with people.

So Timon, once the city’s most open-handed philanthropist (“lover of humans”) now becomes an embittered misanthropist (“hater of humans”). He condemns wealth and the avarice it encourages in persons. Even when he discovers gold while digging for roots to eat, he refuses to use it to return to his lavish lifestyle. He despises it as much, and probably even more, than the cynic Apemantus.12

His erstwhile sycophantic followers, all of whom deserted him when they learned he was broke, soon hear that Timon’s has struck it rich. Predictably, they flock to him with outstretched hands. Timon gives freely. But this time he scatters his wealth with scorn and hatred, declaring his hope that the gold he bestows on his suiters will corrupt and destroy them. The only person who visits him out of concern for his well-being rather than greed is the faithful Flavius, whose kindness nearly, but not quite, causes Timon to question his misanthropy.

At play’s end, Timon leaves instructions to be buried on a beach so that the incoming tides can obliterate any trace of his ever having existed. His hatred of humans is so great that he doesn’t want even his memory to abide with them. And then, abruptly but appropriately, he disappears from the play. There’s no dramatic death scene. Timon just walks off stage and is heard from no more.13

Bad Faith: The Key to Timon

How are we to understand Timon’s vaunted generosity and his startlingly volte-face transition from philanthropy to misanthropy? There are two schools of opinion.

A.D. Nuttall argues that Timon gives freely with no thought of recompense, and just naturally expects everyone to be as open-heartedly generous as he is. That’s why the refusal of his so-called friends to help him in his moment of need shatters his innocent optimism. Dieter Mehl likewise thinks that Timon is authentically generous. His “unworldly blindness” to financial prudence, not to mention his naivete about the hangers-on who want to soak him, lead to his sudden disillusionment.14

Auden, on the other hand, concludes that Timon’s generosity is utterly self-serving. He’s a “pathological giver” who “wants to be a god on whom others depend.”15 When he’s no longer able to strut like a colossus—when his flatters have no more reason to flatter him—he sinks into petulant, self-absorbed rage.

I find Auden’s read more correct than Nuttall’s or Mehl’s. But I think we can be more nuanced than simply concluding that Timon suffers from a god-complex. Marjorie Garber, the best living Shakespeare interpreter, comes closest to what I think is going on when she says that Timon is so “invested in his own persona as a source of endless bounty” that it’s unsurprising he “dwindle[s] into a railing caricature” after going broke.16

Garber’s intuition that Timon’s fatal flaw is “invest[ment] in his own persona” can be fleshed out with Sartre’s understanding of bad faith.

Bad faith, or mauvaise foi, is essentially a form of self-deception. When we fall into it, we deny one aspect of what it means to be a person by overemphazing another. We lock ourselves into an inauthentic or false identity.

According to Sartre, a human is a combination of fact and freedom. Each of us is born into a specific temporal and spatial context and endowed with a biologically determined set of strengths and weaknesses. This is what Sartre calls our “facticity” or our “being.” But we also possess freedom of will, an ability to transcend our facticity, to “negate” the pull of its inertness. He calls this “nothingness.”

Human existence is a balancing act between these two aspects.17 We deceive ourselves about who we are—we’re lapse into bad faith—when we claim one at the expense of the other.

We deny our freedom by convincing ourselves that we’re nothing but facticity, thereby trying to freeze our identity into an object-like permanence.18 “I can’t help it,” someone might say about his sexuality, intellect, or habits. “That’s just who I am! It’s my nature!” Sartre would respond that this assertion is an indication of mauvaise foi, of avoiding the possibilities (and hazards) of freedom and thereby getting stuck in the viscosity of being. A thing, after all, doesn’t have to worry about an uncertain future. It remains what it is.

But trying to become an unchangeable object by focusing on facticity is only one of two ways in which bad faith can occur. The other is by self-identifying as an utterly transcendent being liberated from historical and biological constraints—a kind of free-floating gnosticism, if you will, in which we tell ourselves that we’re essentially mind or spirit and hence untouchably superior to the material circumstances that comprise facticity.19 Persons indulging in this kind of bad faith often pride themselves, says Sartre, on their “purity of heart” or “sincerity.”20 Like practitioners of the first kind of bad faith, they too trick themselves into believing that they’re immune to the worrisome messiness of life.

Bad faith, like any form of self-deception, almost inevitably creates an inner tension. Struggle though they may to deny either their facticity or their freedom, bad-faithed persons never fully succeed: their facticity or their freedom always lurks in the background, haunting them, picking at them, calling their distorted self-appraisals into question. But because they’re so invested in the false identities they’ve created for themselves, they resist the self-reflection necessary to root out the interior source of their disquiet. Instead, they typically lash out at others. They convince themselves that their uneasiness stems from being misunderstood, betrayed, snubbed, or mistreated in some way. Projection is bad faith’s go-to defense mechanism.

Timon’s Self-Deception

The curious thing about Timon is that he displays, in serial fashion, both varieties of bad faith.

In the first half of the play, Timon’s bad faith is of the denying facticity variety. He refuses to acknowledge the material fact that he’s squandering his fortune, thereby transforming his status from wealthy patron to hounded debtor. He’s above such petty, earthbound worries. He dwells in an ethereal realm of pure generosity unblemished by petty concerns about bank accounts and budgets.

So, for example, when Timon lavishes gifts upon fawners at the play’s opening banquet, his faithful steward Flavius tries to warn him against his disastrous prodigality.

“I beseech your Honor,

Vouchsafe me a word. It does concern you near.” (I.ii.184-185)

But Timon grandly brushes him aside:

“Near? Why, then, another time I’ll hear thee.” (I.ii.186)

Later, as Flavius contemplates with alarm the extent of Timon’s financial fall, he despairingly muses:

“No care, no stop, so senseless of expense

That he will neither know how to maintain it

Nor cease his flow of riot. Takes no account

How things go from him nor resumes no care

Of what is to continue.

He will not hear till feel.” (II.ii.1-5,7)

But even feeling doesn’t work with Timon, at least not initially. When Flavius finally manages to corner his master with the bad news that he’s racked up a mountain of debt which he can’t pay, Timon is torn between shock and denial.

“How goes the world that I am thus encountered

With clamorous demands of debt, broken bonds,

And the detention of long-since-due debtors

Against my house?” (II.ii.47-50)

How, in other words, can I be broke? I’m a wealthy and boundlessly generous man! Timon just can’t bring himself to accept the concrete situation in which he’s landed, much less take responsibility for it. Predictably, given the nature of bad faith, there’s a hint of projection here, a subtle suggestion that Flavius the steward must be at fault for not being more careful with his master’s wealth. After all, Timon dwells on the empyrean heights, Flavius on the flat plain of material concerns.

Timon sees himself as the embodiment of unqualified generosity, a bestower of agapic largesse who has no desire or expectation of return. He gives “freely,” he proclaims, and “there’s none / Can truly say he gives if he receives.” (I.ii. 11-12) He assures a petitioner that “More welcome are you to my fortunes / Than my fortunes to me.” (I.ii. 20-21) His generosity is so unbounded that he wishes he could “deal kingdoms to my friends” in addition to the already lavish favors he bestows on them. (I.ii. 233) Moreover, whenever he’s given a gift by another person, he feels the need to respond with an even costlier one. His crowd of hangers-on know this, and gleefully bestow slight favors upon him in anticipation of huge returns.

But from the very start of the play, there’s something suspicious about the authenticity of Timon’s agape. On two separate occasions, he’s told that the recipients of his bounty are forever bound to him (I.i.122,174-176), and in neither instance does he bother to dispute the claim. Moreover, when he finally faces his insolvency and turns to others for loans, it’s pretty clear that he considers them his debtors, even though he never actually says as much. He gave to them out of love, he insists. So surely they’ll act similarly. But this is more self-deception, Timon’s last desperate push to hang on to his bad-faithed self-image and remain free of the brutal facts of life.21

Postmodern philosopher Jacques Derrida’s analysis of gift-giving provides us with another reason to suspect Timon’s self-image as an agapic giver. For Derrida, gift-giving is an inherently impossible act—what he calls an aporia—because there’s always a circle of exchange in which the giver is rewarded for her gift-giving.22 The return is either objective, a reciprocal gift or at least an expression of gratitude, or subjective, an internal feeling of self-satisfaction at having done a good deed. Timon makes a great show of refusing objective rewards, but his high appraisal of his own generosity indicates that he basks in the glow of subjective ones.23 But this, of course, is something he never admits to himself—at least not until he finds himself broke and friendless.

Switcheroo

Once Timon finally acknowledges that he’s out of money and that his hangers-on are nothing but “mouth-friends” and “trencher-friends” (III.vi.91,100), he swiftly transitions from a lover to a hater of humanity: “I am Misanthopos and hate mankind,” he venomously shrieks. (IV.iii.59) It’s at that moment that he exchanges one mode of bad faith—denying his facticity—for its opposite—denying his freedom. Henceforth, Timon will be nothing but a hater of the whole race of humans. His identity is locked in. He has become a thing, an object, a naked fact defined exclusively by hatred with only one desire:

“Grant, as Timon grows, his hate may grow

To the whole race of mankind, high and low!” (IV.ii.39-40)

As a symbol of his descent into thinghood, Timon even takes on the appearance of a thing of the earth. He allows his hair and nails to grow, he gradually becomes encrusted with soil and grime, and he digs in the earth with his hands, almost as if he wants to merge with it, to disappear into it.

Predictably, Timon’s hatred of humankind is a projection of his own inner turmoil. In his mind, his downfall can’t be because of his earlier heedless prodigality. No, the real culprits are money and avaricious men. They’re to blame for both his own ruin and all the other evils in the world. This, of course, is a total reversal of what he once believed: that money is a good because a means of largesse, and that people are worthy of generosity. As Apemantus perceptively says to Timon at one point, “The middle of humanity thou never knewest, but the extremity of both ends.” (IV.iii.341-342) First Timon was superior to material considerations, a disincarnate paragon of generosity: pure freedom. Now he is a thing of the earth, a self-enclosed thing of hate: pure facticity.

Timon’s rage is so murderous that when he discovers gold in his wilderness retreat, he gleefully offers handfuls of it, in a parody of his earlier generosity, to all and sundry who visit him: Athenian rulers, courtesans, Alcibiades, and even bandits. Because money is that instrument which he believes robs persons of their souls, and because he despises humankind, Timon is eager to facilitate the destruction of others by poisoning with riches. Speaking to the gold which he now sees as booby trap rather than boon, Timon says

“O thou sweet king-killer and dear divorce

‘Twixt natural son and sire, thou bright defiler

Of Hymen’s purest bed, thou valiant Mars,

Thou ever young, fresh, loved, and delicate wooer,

Whose blush doth thaw the consecrated snow

That lies on Dian’s lap; thou visible god,

That sold’rest close impossibilities

And mak’st them kiss, that speak’st with every tongue

To every purpose! O thou touch of hearts,

Think thy slave, man, rebels, and by thy virtue

Set them into confounding odds, that beasts

May have the world in empire!” (IV.iii.425-438)24

But it’s not only humans Timon now sees as rapacious and unworthy of life. All of the animal kingdom is adjudged predatory, just one long and gory food chain in which the strong devour the weak just as his hangers-on devoured him when he was still wealthy.25 Nor does the avarice stop there: the physical, inanimate world is likewise replete with “thievery.”

“The sun’s a thief and with his great attraction

Robs the vast sea. The moon’s an arrant thief,

And her pale fire she snatches from the sun.

The sea’s a thief, whose liquid surge resolves

The moon into salt tears. The earth’s a thief,

That feeds and breeds by a composture stol’n

From gen’ral excrement. Each thing’s a thief.” (IV.iii.489-495)

Timon’s bad-faithed projection has reached the outer limits here. Humans, animals, and now the cosmos itself: all are to be distrusted and condemned.

No Name, No Self—No Memory

The cruel irony of bad faith is that even though its victims believe they have a definite identity, either as pure above-it-all freedom or solidly unambiguous object, they’ve in fact robbed themselves of any authentic sense of self. By refusing to accept both aspects of what it means to be human, the being (facticity) as well as the nothingness (freeedom), they lose the opportunity to develop as a person.

This is exactly poor Timon’s fate. Having jumped from one extreme to the other, he lacks a foundation for selfhood. “Thou hast cast away thyself,” one of his interlocutors warns him. (IV.iii.247) And when Alcibiades first runs across Timon the misanthropist huddled at the entrance of his wilderness cave, he doesn’t recognize him. “What art thou there? Speak. What is thy name?” (IV.iii.54, 57) From the perspective of stagecraft, Timon looks different because his hair and beard are tangled, his face grimy, his clothes tattered. But from an existential one, Timon is nameless and unrecognizable because he has no identity. He’s so hidden by the bad-faithed masks he’s worn throughout the play that he’s no longer recognizable even to himself. As Sartre says, self-deception is never totally successful. But it’s destructiveness is very real indeed.

At the end, exhausted by his hatred and sinking ever deeper into earthlike numbness, Timon truly does become as close to an inert, possibility-less thing as it’s possible for a conscious human to be. All he wants is to complete his slide into raw facticity by losing what scraps of awareness he has left.

Given that, what else is left for Timon but simply to disappear? A man with no self and no name has no standing in this world and hence should leave behind no memory. As Timon says to his final visitor right before he vanishes from the play,

“Come not to me again, but say to Athens,

Timon hath made his everlasting mansion

Upon the beachèd verge of the salt flood,

Who once a day with his embossèd froth

The turbulent surge shall cover. Thither come

And let my gravestone be your oracle.”

(Timon exits) (V.ii.246-251)

Later, a soldier reports to Alcibiades that Timon is dead, and that the inscription on his gravestone is being gradually erased by the ebb and flow of the tide. The half-literate soldier scribbled on a wax tablet—signifiantly, a soft and impermanent medium—what he could make out of the epithet.

“Here lies a wretched corse, of wretched soul bereft.

Seek not my name.” (V.iv.82-83)

This final scene symbolically captures the vanishing act which was Timon’s life. His very tomb is being washed away, and what can be read of its quickly disappearing epitaph by a semi-literate soldier is quickly copied onto an easily erasable tablet. Life, for Timon, was an illusion, the self-deception of bad faith, and his self a false construct, an artefact of bad faith. It’s appropriate that Timon’s memory should be lost because he never truly existed.

Why did Shakespeare never stage this tragedy? Perhaps because his insight that self-deception erodes human flourishing even more surely than time does was simply too much for him to face at the time. Later, when he came to write King Lear, he would confront the same theme head-on. But Timon paved the way.

###

Timon of Athens I.i.258. All quotations from Timon are from the Folger Shakespeare Library edition, ed. Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013).

Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology, trans. Hazel E. Barnes (London: Methuen and Co., 1957), p. 49.

The eponymous character’s name is pronounced TIE-mun, not Tee-MONE. Shakespeare isn’t Disney.

Harold Bloom, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (New York: Riverhead Books, 1989), p. 500.

William Hazlitt speaks for them all: “It is the only play of our author in which spleen is the predominant feeling of the mind.” Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays (London: J.M. Dents & Sons, 1921), p. 47. Characters was first published in 1817.

Harold C. Goddard, The Meaning of Shakespeare, Vol. 2 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), p. 173; Donald A. Stauffer, Shakespeare’s World of Images: The Development of His Moral Ideas (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1966), pp. 222, 227. Goddard also suggests, implausibly to my mind, that Sonnet 110 is another bit of therapeutic confession.

The complaint of the Poet, one of the play’s sycophantic characters, is sometimes taken to be an expression of Shakespeare’s own frustration at the need to flatter wealthy patrons. I have my doubts.

“When we for recompense have praised the vile,

It stains the glory in that happy verse

Which aptly sings the good.” (I.i.19-21)

W. H. Auden, Lectures on Shakespeare (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), p. 255.

A.D. Nuttall, Shakespeare the Thinker (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 321.

Bloom, p. 589.

Apemantus is Shakespeare’s invention, but Timon is based on an actual historical figure. Shakespeare drew heavily on Plutarch’s biographies of Antonius (chapter lxx) and Alcibiades (chapter xvi) for his portrait of Timon. He may also have been familiar with Lucian’s “Timon the Misanthrope,” although the major influence is clearly the Life of Antonius, from which Shakespeare pulls several quotes, including the haunting epitaph Timon writes for himself.

Ben Johnson’s Volpone, written in the same timeframe in which Shakespeare likely drafted Timon, also focuses on the vice of avarice and the corrupting nature of money.

There’s a ancillary plot in the play that involves Alcibiades’ feud with the Athenian senate. It parallels the theme of ingratitude that runs through Timon’s storyline. But because the Alcibiades sections seem relatively undeveloped by Shakespeare and in fact don’t add any new thematic content to the play, I omit a discussion of them here.

Nuttall, p. 314; Dieter Mehl, Shakespeare’s Tragedies: An Introduction (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986), p. 205

Auden, pp. 255, 261.

Marjorie Garber, Shakespeare After All (New York: Anchor Books, 2004), pp. 638, 641.

In this regard, Sartre’s dualistic tendencies come to the forefront. He’s more Cartesian than he likes to admit.

Sartre’s famous example in Being and Nothingness (pp. 59-60) is the waiter who thinks of himself as nothing more (or less) than a waiter. This is what restaurant patrons require him to be, and he acquiesces to their demand to such an extent that he identifies with the persona.

Sartre illustrates this form of bad faith in Being and Nothingness (pp. 55-56) with the example of a woman who refuses to acknowledge that a male companion sees her as a potential sex partner, while she insists on thinking of herself as more of a mind than a body.

Being and Nothingness, p. 58.

Coppélia Kahn’s feminist reading of the play likewise discerns a suspiciously aggressive quality to Timon’s gift-giving. See her “‘Magic of bounty’: Timon of Athens, Jacobean Patronage, and maternal Power.” Shakespeare Quarterly 38 (1987): 34-57.

See Derrida’s Given Time: 1. Counterfeit Money (Carpenter Lectures), trans. Peggy Kamuf (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

In his thought-provoking “‘One Wish’ or the Possibility of the Impossible: Derrida, the Gift, and God in Timon of Athens.” Shakespeare Quarterly 52 (2001): 34-66, Ken Jackson comes to a completely different conclusion about Timon the giver’s authenticity. His piece is well worth reading.

The young Marx was so struck by Timon’s denunciation of money that he quoted several passages from the play in one of his early essays: “The Power of Money in Bourgeois Society” in The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, trans. Martin Milligan (New York: International Publishers, 1964), pp. 165-169.

Timon is replete with cannibalistic images of eating and devouring. See, for example, I.i.235, 287-288, 309; I.ii.40-43; III.iv.61, 125; III.vi.90-104; IV.iii.468, 477; V.i.60.