“The wound, which causes us to suffer now, will be revealed to us later as the place where God intimated his new creation.” —Henri Nouwen1

Shortly before he faces a firing squad, the “whisky priest” protagonist of Greene’s The Power and the Glory realizes that “at the end there was only one thing that counted—to be a saint.”2

What exactly does it mean to be a saint? The best short answer just might be St. Irenaeus’ “The glory of God is a human being fully alive.”3 But that raises a second question: whatever does that mean?

This is where Greene’s novel helps out. In it, he offers us a portrait of a person—the hounded whisky priest—who drinks to cope with his interior demons and external hardships, craves to love and be loved but feels unworthy of either, condemns his own failings while pardoning those of others, fears death yet sacrifices himself, and displays an honesty, dignity, faith, and humility born from deep woundedness, not some hagiographic caricature of holiness.

Hemingway famously wrote that even though the world breaks everyone, some survivors are stronger for their brokenness.4 This, I think, is what it means to be a fully alive human being: not just to acknowledge and endure but to struggle with courage, determination, and hope against one’s own weaknesses. And saints? These are fully alive humans who manage to transfigure their wounds, their own experiences of deep suffering—and yes, even their sins—into acts of compassion, love, and kindness. In a curious way, then, brokenness is a necessary condition for saintliness—or, in more traditional terms, for the reception of grace.

This is Greene’s whisky priest. Even though he never realized it, he achieved the one thing that counted, as we’ll discover in this seventh installment of the ongoing Presence of Grace series’ exploration of Catholic novels.5

Doubting Thomas in Mexico

In many of his novels, especially his so-called Catholic ones,6 Greene offers us a motley array of broken characters. This wasn’t simply artistry on his part. It reflected his awareness of the wounds he himself carried.

Melancholy, or what he later acknowledged as manic depression, plagued Greene most of his life. Even as a youth, he suffered from alternating periods of flattened affect—what he typically referred to as boredom— and tense restlessness. Both prompted him to seek relief in a number of shocking ways.

In the autumn of 1923, for example, when barely nineteen years old, Greene turned to Russian roulette to break the monotony of his existence. Putting a revolver to his head, pulling the trigger, and hearing the click of an empty chamber, he experienced “an extraordinary sense of jubilation, as if carnival light had been switched on in a dark drab street.” The risk of losing everything made it possible for him “to enjoy again the visible world.”7 On another occasion, he faked an abscessed tooth so that the attending dentist would put him under with ether. “A few minutes’ unconsciousness was like a holiday from the world. I had lost a good tooth, but the boredom was for the time being dispersed.”8 Beginning in his early thirties, he adopted continuous travel and serial love affairs to cope with his uneasy restlessness.

Never a particularly religious youth—“religion went no deeper than the sentimental hymns in the school chapel”9—Greene converted to Roman Catholicism in 1926 in order to marry. He received catechetical instruction and read enormous amounts of theology, eventually becoming convinced of the “probable existence of something we call God.”10 But the modifier “probable” is telling; ambivalence would define his religious sensibilities for the rest of his life. He chose as his baptismal name Thomas—“after St. Thomas the doubter and not Thomas Aquinas”11 —and felt no joy, but only a “somber apprehension” when received into the Church. He confessed to being less and less interested in religion and God as he aged.12 As he revealingly wrote in his fifties, “We make a cage with air for holes, and man makes a cage for his religion in much the same way—with doubts left open to the weather and creeds opening on innumerable interruptions.”13

Greene’s conversion was primarily an intellectual one. It was only a decade later, when he traveled to Mexico to explore the institutional repression that resulted in “empty and ruined churches from which the priests had been excluded,”14 that Greene’s personal religiosity moved, at least for a while, from his head to his heart. “I had no emotional attachment to Catholicism,” he recalled in a 1980 interview, “till I went to Mexico and saw the faith of the peasants during the persecution.”15 His time there, which opened up a channel of grace for Greene that surprised him, resulted in a travel book, The Lawless Roads (1939),16 and then, a year later, The Power and the Glory, a novel focused, he later wrote, on “the appalling strangeness of the mercy of God.”17

Anti-clericalism, fueled by the angry perception that the Church enjoyed an inordinate degree of political and economic privilege, had been simmering in Mexico throughout most of the nineteenth century. But the new 1917 Constitution codified it by authorizing the seizure of Church property, the persecution of clergy, the elimination of religious orders, the prohibition of public demonstrations of faith, and the discouragement of private devotion, all geared towards weeding out Catholic tares from the secular wheat.

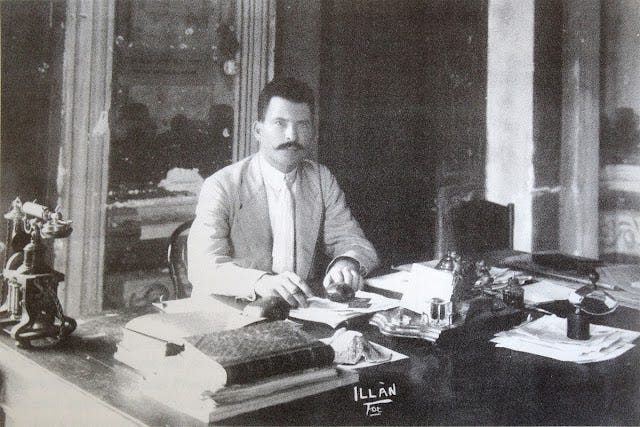

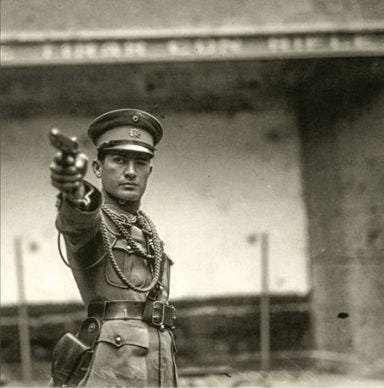

Mexican states differed in the degree to which they enforced the new anti-clerical laws. But several of them, especially Tabasco, were notoriously harsh. Governed by Tomás Garrido Canabal, Tabasco’s official campaign against Christianity was waged by the Red Shirts, an army of 6,000 young men whose sole purpose throughout the 1920s was to rid the state of all traces of religion. They desecrated churches, burned religious statues, demolished gravestones bearing Christian symbols, and routed out priests who had gone underground, forcing them either to renounce their vows and marry or face execution. Red Shirts also routinely raided private homes in search of religious emblems. Even saying adios was deemed a punishable offense.18

Greene arrived in Mexico in 1938, anxious to explore the effects of nation’s official godlessness. By that time, repression of the Church had ameliorated in large areas of the country. So he headed to Tabasco and Chiapas, where anti-clerical measures were still alive and well. His observations there of the persecuted Church added existential fiber to his hitherto abstract theological diet, and from this was born his single greatest novel about a priest on the run from the authorities in a region where Christianity has been outlawed.

Hollowed be Our Names

When we meet the whisky priest, he’s been on the run for a decade, desperately trying to sneak out of Tabasco before the Red Shirts track him down. He’s a cadaverously thin man with the beaten look, “in his hollowness and neglect, of somebody of no account.”19

Before the persecutions began, however, he’d been a man very much of account. A “fat youngish priest,” smug in his faith and confident in his abilities, he’d imagined “a whole serene life” stretching out in front of him. To his mind, there was even “no reason why one day he might not find himself in the state capital, attached to the cathedral.”20 He’d had a high opinion of his own sanctity—so much so, that he remained in Tabasco even when his clerical colleagues fled after the churches where shut down. He alone would hold the line. He would be a suffering-servant saint, a defender of the faith, comfort in a troubled time to a captive people.

But it didn’t take long for things to fall apart for him. Without external incentives to behave in a manner befitting his priesthood, his smug sense of vocation was exposed for the delusion it was. He became a hounded, frightened fugitive, neglectful of his spiritual health, dependent on brandy for dutch courage. As he confesses in a moment of brutal self-honesty,

“One thing went after another. I got careless about my duties. I began to drink. It would have been much better, I think, if I had gone too. Because pride was at work all the time. Not love of God. […] I thought I was a fine fellow to have stayed when the others had gone. And then I thought I was so grand I could make my own rules. I gave up fasting, daily Mass. I neglected my prayers—and one day because I was drunk and lonely—well, you know how it was, I got a child. It was all just pride. Just pride because I’d stayed. I wasn’t any use, but I stayed.”21

The whisky priest clearly doesn’t display the sort of frozen perfection popular piety demands of its saints. That role is filled—and shown to be the caricature of genuine sainthood it is—by two other characters in the novel: Juan, the boy-hero of a treacly hagiographical book read by a mother to her son and daughter, and an unnamed lieutenant, an officer in the Red Shirts obsessed with wiping out the final remants of Christianity from the state of Tabasco.

Young Juan is the perfect boy, possessing a creepily preternatural solemnity even as a child, forever mouthing pious Sunday School platitudes about the Father in heaven, forever playing the cookie-cutter role of apprentice saint. Luis, the son who finds the inauthenticity of Juan’s story increasingly unbearable, finally can take no more of it and storms out of the room, shouting, “I don’t believe a word of it, not a word of it!”22 He correctly senses what his conventionally religious mother cannot: that the Juan of the story is too perfect, too exemplary, too one-dimensionally goody-goody, to be real. Juan would never grow up to be a human fully alive, much less a saint. Nor would he ever be a whisky priest. He just doesn’t have the depth for it.

The lieutenant, on the other hand, displays both depth and genuine dedication. A rigidly self-disciplined man who practices monastic severity in his personal life, he’s utterly devoted to liberating his fellow citizens, whom he loves in the abstract but despises for their ignorance and superstition, from the clutches of the Church. Unlike the whisky priest, the lieutenant suffers from no ambivalence about his calling. Nor does he allow himself the occasional break from the straight-and-narrow path he’s made for himself. His uniforms are stiffly starched and impeccable. So is his conscience.

But in fact the lieutenant is a nihilist. He tells himself that he persecutes the Church on behalf of the people: “it was for these he was fighting. He would eliminate from their [lives] everything which had made him [in his youth] miserable, all that was poor, superstititous, and corrupt. They deserved nothing less than the truth.”23 But the “truth” he wants to give them—to force upon them—is that they’re sojourners in an empty, meaningless universe.

“There are mystics who are said to have experienced God directly. He was a mystic too, and what he had experienced was vacancy—a complete certainty in the existence of a dying, cooling world, of human beings who had evolved from animals for no purpose at all. He knew.”24

The whisky priest’s gauntness makes him look hollowed out. But young Juan, on the fast track to becoming a cast plaster saint, and the lieutenant, a missionary dedicated to spreading the dysangelion of nothingness, are genuinely hollow. On the surface, they come across as closer to sainthood than the whisky priest. But this says more about our distorted conventional notions of sainthood than its actual nature, a distinction Graham is eager to impress upon his readers.

The Grace of Unrepentant Love

The whisky priest lacks the perfect rectitude and austerity of either Juan or the lieutenant. His years of running from the Red Shirts, hiding in jungles, starving (so much so that at one point he wrestles a crippled dog for a bit of rancid meat25), and drowning in an ocean of loneliness have left him a broken, wounded man. As we’ve already seen, his suffering has replaced his pre-persecution pride with a bitter recognition of his failings.

This is an insight foreign to Juan and the lieutenant. Juan is too perfect to have an interior; a person without any faults has no soul to examine. For his part, the lieutenant is too consumed by zealous rage to waste time on self-reflection, much less doubt. But the whisky priest is cut from a different cloth. “I tell you,” he says at one point, “I am in a state of mortal sin. I have done things I couldn’t talk to you about. I could only whisper them in the confessional.”26 The problem, of course, is that no other priest is left in Tabasco to offer him the sacrament of reconciliation.

But even if there were, the whisky priest is honest enough with himself to admit he wouldn’t be able to make a good confession. Why? Because he was unrepentant. “He couldn’t say to himself that he wished his sin had never existed, because the sin seemed to him now so unimportant and he loved the fruit of it.”27

The sin he’s referring to was committed a few years back when his desperate loneliness, not to mention a snootful of liquor, got the better of him. He lay with a woman, and from their loveless fumbling in the dark a girl-child, Brigitta, was born.

The whisky priest visits the girl and her mother only rarely; with the Red Shirts on his heels it’s too dangerous to linger in any one locale very long. So Brigitta barely knows him, and certainly doesn’t love him. In fact, her typical response to him is a mixture of suspicion and scorn. But the whisky priest loves her so deeply, so desperately, that he’s willing to sacrifice everything for her. “O God,” he prays, “give me any kind of death—without contrition, in a state of sin—only save this child.”28

In one of the novel’s most moving and revelatory scenes, the whisky priest kneels before Brigitta.

“‘I love you. I am your father and I love you,’ he tells her. ‘Try to understand that.’ He held her tightly by the wrist and suddenly she stayed still, looking up at him. He said, ‘I would give my life, that’s nothing, my soul … my dear, my dear, try to understand that you are—so important.’ That was the difference, he had always known, between his faith and theirs, the political leaders of the people who cared only for things like the state, the republic: this child was more important than the whole continent.”29

How could he repent having made her? True, the act of sex was a betrayal of his priestly vows. But the love the whisky priest feels for the child, a love that came to him only because of his moral failure, was pure and holy—saintly.

Moreover, the love awakened in him by his child invigorates rather than jeopardizes his priestly vocation. The priest he was in the days before persecution knew nothing about love; but the broken man he now is stretches to help others in distress, even if he does so reluctantly. He passes up several opportunities to flee Tabasco because he simply can’t turn his back on villagers who implore him to celebrate Mass for them, hear their confessions, bury their dead. Does he “feel” love for them? Probably not. In fact, he often resents their demands: they keep asking, asking, asking, gradually stripping him of the hope of escaping the godless land. But he serves them at great physical and psychological cost to himself. Love, as St. Thomas Aquinas insisted, isn’t so much an emotion as a willingness to act for another’s well-being, even at the risk of one’s own.30 This is what the whisky priest does—not in spite of but because of his wounds, the wounds of love.

Such is the paradox of grace, what Greene referred to as the appalling strangeness of God’s mercy. The whisky priest has some glimmering of that strangeness, as should we all.

“It sometimes seemed to him that venial sins—impatience, an unimportant lie, pride, a neglected opportunity—cut you off from grace more completely than the worst sins of all. Then [in pre-persecution days], he had felt no love for anyone; now in his corruption he had learnt…”31

Reaching Vera Cruz

Throughout his years in the Tabasco wilderness, the whisky priest dreams of somehow making his ways to Vera Cruz, a Mexican state free of Red Shirts and persecution. Vera Cruz: True Cross. If only he can kneel at the foot of the True Cross, caress the feet of his Savior, he’ll at last be safe.

But just as he finally has a real chance of making his way there, a mestizo, a shady, predatory character—“he had only two teeth left, canines which stuck yellowly out at either end of his mouth”32—comes to him with the plea that he travel back into the interior of Tabasco—the heart of darkness—to give last rites to an American bandit wounded in a shootout with police. The whisky priest has had past dealings with the mestizo, and knows him to be a “Judas”33 eager to collect the bounty offered for his capture. So he’s pretty confident that he’s being enticed into a trap. But he also knows that a dying man has requested his priestly services. So he goes.

In what must seem to the whisky priest an act of cruel mockery on God’s part, the wounded man refuses the offer of last rites just as the lieutenant arrives on the scene to arrest him. Thrown into a cell to await his execution, he’s given a bottle of brandy—more dutch courage—to fortify him on his final night on earth. It’s a gesture of pity, perhaps, but also of contempt.

Between draughts of the liquor his thoughts seesaw back and forth between love for his daughter, guilt for his failings, and fear of what awaits him at dawn.

“He said, ‘Oh God, help her. Damn me, I deserve it, but let her live for ever.’ This was the love he should have felt for every soul in the world: all the fear and the wish to save concentrated unjustly on the one child. He began to weep; it was as if he had to watch her from the shore drown slowly because he had forgotten how to swim. He thought: This is what I should feel all the time for everyone. […] He prayed, ‘God help them,’ but in the moment of prayer he switched back to his child and he knew it was for her only that he prayed. Another failure. […] What an impossible fellow I am, he thought, and how useless. I have done nothing for anbody. I might just as well have never lived.”34

When morning comes, the priest is too drunk—and too frightened—to walk on his own to the execution wall. He was to be supported, one on either side, by two Red Guards. Just before the volley is fired, he raises his hand and shouts something that sounds like “Excuse!”35 Then it’s over. In experiencing his own Golgotha, he finally arrives at Vera Cruz. And it’s the Lord who caresses his feet, not the other way around.

The whisky priest is unnamed for a good reason: he’s everyperson. God’s intent is that every human be fully alive and even become saints. At the end of the day, that’s what finally counts.

What this requires is that we risk the wound of love that opens our eyes to our own shortcomings and makes us vulnerable in a world that too often discounts love as a weakness to be taken advantage of. Both the shortcomings and the vulnerability can be openings through which grace flows to make us new creations. Like the whisky priest, we may feel our brokenness so bitterly, so humbly, that we never quite realize we’ve arrived at the one thing that counts. We may lament that we haven’t loved well or widely enough. But to love even one person with a full heart is to love well, and loving well always overflows its intended object. God knows this, even if we don’t.

###

Henri J. M Nouwen, The Wounded Healer: Ministry in Contemporary Society (New York: Image Books, 1979), p. 96.

Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory (New York: Penguin, 1971), p. 210. Leon Bloy agrees. The ultimate sadness, he declares in one of his novels, is not being a saint: La Femme Pauvre (Paris: Éditions De Borée, 1957), p. 464. “Il n'y a qu'une tristesse . . . , c'est de N'ÊTRE PAS DES SAINTS.” (Emphasis in the original.) So does Thomas Merton and his friend, poet Robert Lax. After Merton’s conversion, Lax asked him what he wanted to be. A good Catholic, Merton somewhat lamely answered. Wrong, replied Lax. “What you should say is that you want to be a saint.” All that’s necessary, Lax then assured Merton, is the desire to be one. Although flummoxed at the time, Merton grew into Lax’s way of thinking. Thomas Merton, The Seven Storey Mountain (New York: Harvest, 1998), p. 260.

Irenaeus, Adversus haereses, IV.xx.vii: “Gloria enim Dei vivens homo.” The Latin only implies “fully,” but I think it’s clear that’s what Irenaeus intended. Why else would he modify homo with vivens? Surely a merely “living” human, much less a dead one, doesn’t glorify God.

Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms (New York: Scribner, 2014), p. 216. “The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places.”

Here are previous chapters in the Presence of Grace series:

So, What Exactly is a Catholic Novel? (31 December 2023)

Surge, Urbana?: J.F. Powers’ Morte d’Urban (8 January 2024)

Motes and Planks: Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood (9 February 2024)

A Longing for Something We Can’t Name: A.G. Mojtabai's Thirst (5 March 2024)

The Heart’s Deep Longing: François Mauriac's Vipers' Tangle (27 June 2024)

The Many Faces of God: Shusaku Endo’s Deep River (16 October 2024)

Although he disliked being typecast as a Catholic author, five of Greene’s novels especially deal with Catholic themes: Brighton Rock (1938), The Power and the Glory (1940), The Heart of the Matter (1948), The End of the Affair (1951), and A Burnt-Out Case (1960). I’d add his late novel Monsignor Quixote (1982) to this list. Although not a novel, his play The Potting Shed (1956) is also worth noting. For Greene’s objection to being declared a Catholic author, see his Ways of Escape (Toronto, Ont: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1980), p. 58.

Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (New York: Pocket Books, 1973), p. 114.

Ibid., p. 137.

Ibid., p. 142.

Ibid., p. 146.

Ibid., p. 147.

See, for example, A Sort of Life, p. 146, and the BBC Two Late Show on the occasion of Greene’s 1991 death. The title character in Greene’s short story “A Visit to Morin” likely represents his mature religious beliefs. Graham Greene, Complete Short Stories (New York: Penguin, 2005), pp. 249-263.

Graham Greene, The Quiet American (New York: Penguin, 1987), p. 87.

Ways of Escape, p. 60.

Maria Couto, Graham Green: On the Frontier (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988), p. 220.

Although impressed by the resilience of Mexican peasants, Greene had little positive to say about Mexico itself. In The Lawless Roads, his scorn for the country became the book’s rather tedious backdrop. Reviewers were quick to pick up on this. One of them sarcastically wrote that “one tires of Mr. Greene’s dyspeptic descriptions of the hotels, the meals, and the sanitary facilities of Mexico.” Another quipped that “one suspects that, even at the North Pole, Mr. Greene would be harassed by mental mosquitoes.” Quoted in Norman Sherry, The Life of Graham Greene. Volume 1: 1904-1939 (New York: Viking, 1989), p. 695.

Ways of Escape, p. 60.

Mexico’s official persecution of the Church eventually resulted in a three-year civil war, often referred to as the Cristero, that pitted Catholics against government troops, especially in the central western states. For more on the war, see David C. Bailey, Viva Cristo Rey!: The Cristero Rebellion and the Church-State Conflict in Mexico (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1974) and Jean A. Myers, The Cristero Rebellion: The Mexican People Between Church and State 1926–1929 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

The Power and the Glory, p. 14. It’s worth mentioning that a hatchet job biography of Greene, Michael Shelden’s Graham Greene: The Enemy Within (New York: Random House, 1994), makes the ridiculous argument that Greene’s description of the whiskey priest as hollow is a riff on T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Hollow Men,” and is meant by Greene to symbolize the hollowness of Christianity. It’s as if Shelden hadn’t actually read the novel.

The Power and the Glory, p. 93.

Ibid., p. 196.

Ibid., p. 50.

Ibid., p. 58.

Ibid., pp. 24-25.

Ibid., pp. 143-145. This is one of the most vividly written scenes in the entire novel.

Ibid., p. 127.

Ibid., p. 128.

Ibid., p. 82.

Ibid.

“To love is to wish good to someone. Hence the movement of love has a twofold tendency: towards the good which a person wishes to someone, and towards that to which he wishes some good.” Summa Theologica I-II.26.4.

The Power and the Glory, p. 139.

Ibid., p. 84.

Ibid., p, 91.

Ibid., pp. 208, 210.

Ibid., p. 216.

Makes me want to read this, but DANG I don't have time for a novel at the moment !!