“This is the violence of love, of giving more than the law demands, of an asceticism like John the Baptist’s, but in the face of which even John is less than the least in the kingdom.” —Flannery O’Connor1

“Active love is a harsh and dreadful thing when compared with love in dreams.” —Fyodor Dostoevsky2

It’s a funny thing. Most of us would gladly say that we value love and want more of it in our lives. But what if the truth is that deep down we’re frightened of love—I mean real love, not the softly domesticated, feel-good, sentimental mush we typically substitute for it—and spend more energy than we’d like to admit shying away from it?

Poet Wallace Stevens said that we moderns have flattened out the Holy. We’ve turned the fiery Paraclete into a caged parakeet and the roaring Lion of Judah into a fat and lazy pussycat. The Holy’s electrifying presence and power—what Flannery O’Connor so strikingly calls the “terrible speed of mercy”3—is simply too much for us. We demand that our encounters with the Divine be pleasantly innocuous. We want the fascinans without the tremendum.4 “Religious feeling,” wrote O’Connor, “has become, if not atrophied, at least vaporous and sentimental.”5

I think we’ve timidly flattened out love for the same reason: we sense, even if only dimly, that fully opening ourselves up to it can demolish us. “To commit oneself to love is to ask for destruction—Christ’s experience is the proof of it,” observed Rosyln Barnes, one of O’Connor’s friends. “If only we were all so capable of taking destruction as He!”6 She wrote this in one of the last letters she mailed before vanishing without a trace while on a mission trip to Chile. When it came to love, Barnes gave more than the law demands.

In no other season of the Christian calendar is love so sentimentalized as it is at Christmas. Perhaps the blessing associated with the final week of Advent—love—is intended to cut through the gauze and remind us that the Nativity is a nova-burst of holy love that electrifies the old world and shatters the stone casing of the human heart. That’s the regenerative violence of love recognized by O’Connor and Barnes. That’s why Dostoevsky’s Elder Zossima says that genuine love, not the dreamily sentimental kind, is harsh and dreadful.7

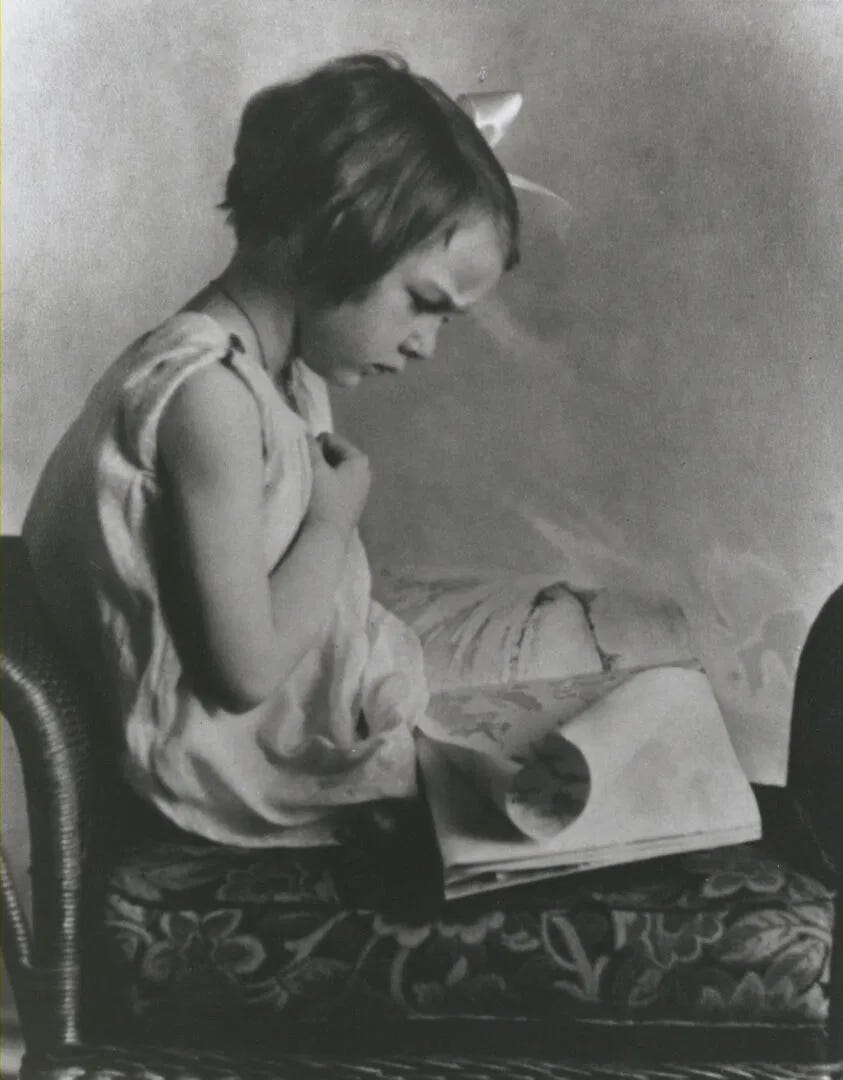

As a child, O’Connor felt securely loved by her parents, not to mention a small army of uncles and aunts, and I’m sure she loved them in return. But in a journal she kept while barely twenty years old, she expressed an urgent hunger for a depth of love that, she hoped, would plunge her into the very heart of God.

“I don’t want to be doomed to mediocrity in my feeling for Christ. I want to feel. I want to love . . . [My soul’s] demands are absurd. It’s a moth who would be king, a stupid slothful thing, a foolish thing, who wants God who made the earth, to be its Lover. Immediately.”8

“O, that Thou wouldst kiss me with the kisses of Thy mouth,” as the King James Bible’s Song of Solomon so achingly puts it. That Thou wouldst incinerate me in Thy embrace, for Your love is better than wine.9

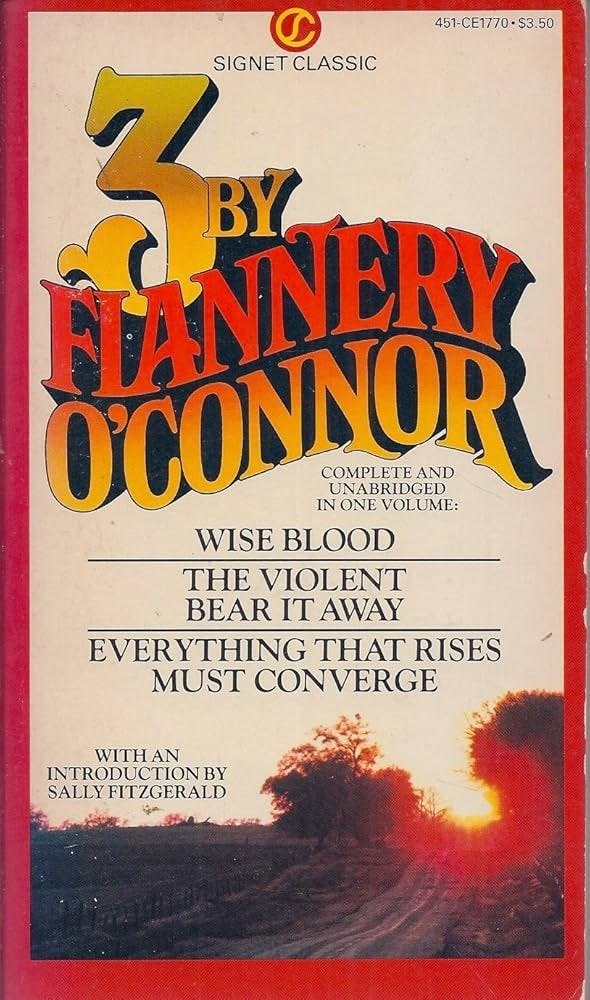

Hints of how O’Connor envisioned this kind of love are scattered throughout her writings. But her own favorite stab at voicing it is in her 1960 novel The Violent Bear It Away. It centers on a father’s (named Rayber) relationship with his simple-minded son (named Bishop). As O’Connor confessed in one of her letters, “Rayber’s love for Bishop is the purest love I have ever dealt with.” It was, she significantly added, a “terrifying purity.”10

Rayber is a middle-aged school teacher who long ago repudiated his evangelical roots. Insisting that the universe is both orderly and exhaustively comprehensible, he finds faith both irrational and psychologically harmful. Like Napoleon’s astronomer Laplace, he feels no need for the God hypothesis and is disdainful of those who do.

But for all Rayber’s desire to be cold-bloodedly analytical in his approach to life, he feels the influence of the “seeds” planted in him years earlier by his fundamentalist uncle Mason Tarwater. Rayber’s wariness of any vestigial trace of zeal in himself translates into a suspicion of emotions in general, and he struggles in a faux-stoical sort of way to suppress them. “The affliction [of strong emotions] was in the family . . . Those it touched were condemned to fight it constantly or be ruled by it . . . He, at the cost of a full life staved it off . . . He kept it from gaining control over him by what amounted to a rigid ascetic discipline.”11

As Rayber somewhat pathetically puts it, “I weed it out.”12

But there’s a fly in the ointment: his son, Bishop, a developmentally challenged boy who “looked like an old man grown backwards to the lowest form of innocence.”13 A sweet child who delights in splashing in fountains and licking mustard off his hamburger bun, Bishop will always have the mentality of a toddler. His brokenness can be easily diagnosed by the science Rayber contends is a sufficient explanation for everything: “the little boy was part of a simple equation that required no further solution.”14 But what a coldly clinical fidelity to science can’t account for is Rayber’s fierce and (for him) frighteningly mysterious love for the lad.

There were “moments when with little or no warning he would feel himself overwhelmed by the horrifying love”15 he felt for Bishop, a love that threatened to overflow to embrace all of creation. “If, without thinking, he lent himself to it, he would feel suddenly a morbid surge of the love that terrified him—powerful enough to throw him to the ground in an act of idiot praise. It was completely irrational and abnormal.”16

It was, in short, an electrifying force before which Rayber feels powerless.

It isn’t that Rayber repudiates all forms of love. “He wasn’t afraid of love in general,” the kind of measured, controlled, and rational affection practiced by measured, controlled, and rational people. But his love of Bishop was of a “different order entirely.”17

“It was not the kind that could be used for the child’s improvement or his own. It was love without reason, love for something futureless, love that appeared to exist only to be itself, imperious, and all demanding, the kind that would cause him to make a fool of himself in an instant.”18

The most searing scene in a novel that shocks on almost every page is when Rayber, “his hated love gripping him and holding him in a vise,” hopes to rid himself of the family affliction once and for all by drowning Bishop. But as he holds his frantically struggling son under water, he experiences “a moment of complete terror in which he envisioned his life without the child” and pulls back.19

How to understand Rayber’s tortured feelings and horrifying treatment of Bishop? O’Connor’s explanation, which can be found in her letters,20 is that whenever we love another person, the ultimate pull is our intuition, howsoever dim it may be, of the divine image in which that person is made.21 Even Rayber the skeptic senses the presence of the Holy in Bishop; for all his corporeal brokenness, the innocent boy is a beacon of the very God from whom Rayber has tried for years to flee. As O’Connor explains,

“He [Rayber] did love him [Bishop], but throughout the book he was fighting his inherited tendency to mystical love. He had the idea that his love could be contained in Bishop but that if Bishop were gone, there would be nothing to contain it and he would then love everything, and specifically Christ.”22

In his wild surges of love for Bishop, Rayber comes too close to the annihilating love, the better than wine kiss, of God. In trying to destroy Bishop, part of Rayber hopes to elude it; but another part of him, realizing that the boy serves as his firewall against falling headfirst into the consuming flames of Holy Love, is terrified at the exposure Bishop’s death would bring him.

To mix metaphors: what Rayber realizes is that if he drowns Bishop, he himself risks being drowned in God.

Rayber’s logic is twisted and turned in on itself several times over, isn’t it? But this isn’t simply a classic example of O’Connoresque grotesquerie. It’s also a penetrating insight into the essential aversion/attraction-tremendum/fascinans we humans experience when it comes to love. On the one hand, we long for a genuine love that can burn away our self-regard and allow us to fully experience the transformative in-rush of the Holy. But on the other, there’s our frightened, frequently cockeyed, and sometimes destructive scrambling to flee the Burning Bush that beckons us to leap into its fiery heart.

Such is the violence, the harshness and dreadfulness, of love. As O’Connor says, it’s imperious and demanding. It insists on peeling away our inhibitng self-deceptions, rationalizations, and anxieties so that the God-likeness with which we’re stamped can explode in our hearts like a nova—much like the one that burst over Bethlehem—and rebirth us. True, we shrink at being wrenched from our comfortably sentimentalized notions of love, even as we long to be carried away by the terrible speed of mercy. We fear and we long to love God and one another as God loves us.

“Because [we] know the consequences of sin,” wrote O’Connor, “[we] know how deep in [we] have to go to find love.”23 The spiritual gift offered us in the fourth week of Advent urges us to throw caution to the wind.

Duc in altum!, says the Lord. Dive deeply into love and let yourself drown in it!

Just as He Himself did, beginning in that humble stable, so many years ago.

###

This is the final installment of the “A Flannery O’Connor Advent” series. Earlier ones are linked below.

Week 1: Hope, Crescent Moons, & Fiery Sunsets

Flannery O’Connor to Dr. T. R. Spivey (16 March 1960), in The Habit of Being: Letters of Flannery O’Connor, ed. Sally Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979), p. 382.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002), p. 58.

Flannery O’Connor, The Violent Bear It Away, in Three by Flannery O’Connor (New York: Signet, 1983), p. 267.

One of O’Connor’s most frequent complaints was that Catholic readers wanted undisturbing, mildly inspiring “apologetic fiction” which makes the Christian story “look desirable so [the reader] won’t look like a fool for holding it.” In a culture of genuine Christian believers, O’Connor sourly concludes, “this wouldn’t come up.” Flannery O’Connor to Sister Mariella Gable (4 May 1963), in The Habit of Being, p. 516.

Flannery O’Connor, “Novelist and Believer,” in Manners and Mystery: Occasional Prose (ed) Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1970), p. 161.

Roslyn Barnes to Fr. James McCowan (Friday August 1964), in Good Things Out of Nazareth: The Uncollected Letters of Flannery O’Connor and Friends, ed. Benjamin B. Alexander (New York: Convergent, 2019), p. 338.

In a passage from the final, unfinished novel O’Connor was working on at the time of her death, one of her characters quotes St. Jerome: “Love should be full of anger.” Jessica Hooten Wilson has done all of us a great service in piecing together the manuscript. See Wilson’s Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage?: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Work in Progress (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2024), p. 32.

Flannery O’Connor, A Prayer Journal (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), pp. 35, 38-39.

It’s worth keeping in mind that this Song of Solomon line poetically captures one of the greatest theo-spiritual truths. To adore someone is to be so intimate, so close, that the two breathe in each other’s mouth: ad = towards + ora = mouth. So the longing to be kissed by the divine Beloved in the Song is spot-on.

Flannery O’Connor to “A” (5 March 1960), in The Habit of Being, p. 379.

Flannery O’Connor, The Violent Bear It Away, pp. 192-193.

Ibid., p. 236.

Ibid., p. 191.

Ibid., p. 192.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., pp. 208, 209.

O’Connor, like many authors of fiction, loathed “explaining” her stories. In her letters, she throws some her most scornful (and funniest) darts at academics and their students who insist that she explain the “deep meaning” behind her work.

Flannery O’Connor to Alfred Corn (30 May 1962), in The Habit of Being, pp. 476-477.

Flannery O’Connor to Alfred Corn (25 July 1962), in Ibid., p. 484.

Flannery O’Connor to Cecil Dawkins (9 December 1958), in Ibid., p. 308.