“He is out of his mind.” Mark 3:21

“She is a challenge to our theology, psychology, medicine.” —Pére Henri Marriott

Insipid prayer cards of our youth trained many of us to want our saints to be other-worldly spirits, their humanity diluted to an ethereal vanishing-point. We prefer, as C.S. Lewis once noted, to sip watered-down sanctity rather than take it straight-up.1

Yet both scripture and centuries of experience warn us that the real saints jolt our sensibilities and conventions like a quick shot of rye slams the gut. This was the point an exasperated Jesus tried to get across when he scolded nay-sayers for kvetching about the disreputably countercultural approach of John Baptizer. What did you come out here expecting to see? he demanded of them. A pasty-faced weakling, a reed swaying in whichever direction the wind blows? Or maybe you were looking for a high-and-mighty man of the world who’d give you “practical” advice on how to cozy up to God? No! he shouted. What you got was a real human being, warts and all, touched by God! Deal with it! In fact, exult in it! (cf. Mt 11:7-9; Lk 7:24-27)

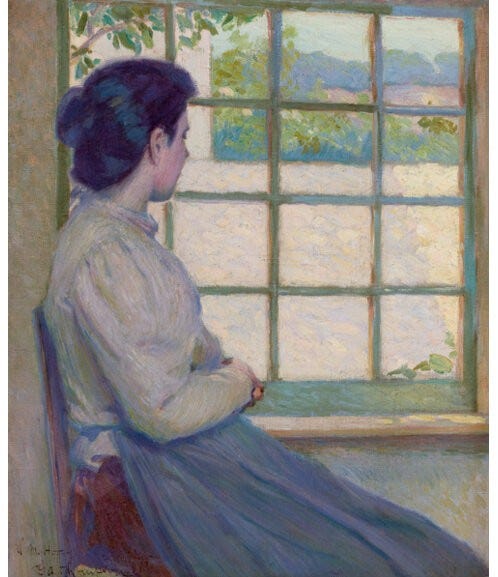

Ron Hansen’s haunting novel Mariette in Ecstasy offers us a portrait of a real human being, a teenager named Mariette Baptiste, who likewise is touched by God—or at least might be—and who scandalizes prim and proper folk as much as John Baptizer did.

That’s because Mariette is a cracked vessel. As she portentiously insists, her name is pronounced “Mar-iette, like a flaw,” not “Mare-i-ette, like a horse.”2 So right off the bat there’s a hint that her religious ecstasies might be symptoms of what psychologists of her era (the early twentieth century) called psycho-sexual hysteria. The genius of Hansen’s story is that he leaves the question open, refusing to offer readers either a slick prayer card or a reductive psychological diagnosis. It’s up to us to judge whether Mariette is a John Baptizer or just an overwrought adolescent girl—or, perhaps, both.

Heartbreakingly Beautiful Writing

Before turning to a discussion of the novel’s themes, I can’t forbear celebrating the jawdropping beauty of Hansen’s writing. The novel is a prose poem, tatting delicate verbal lace-works that evoke moods of silence, emptiness, mystery, and grace. Of the six Catholic novels previously explored in this Presence of Grace series,3 Hansen’s is the most exquisite. (A.G. Mojtabai's A Longing for Something We Can’t Name is a close second.)

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about:

“Half-moon and a wrack of gray clouds.

Church windows and thirty nuns singing the Night Office in Gregorian chant. Matins. Lauds. And then silence.

Wind, and a nighthawk teetering on it and yawing away into woods.

Wallowing beetles in green pond water.

Toads.

Cattails sway and unsway.

Grape leaves rattle and settle again.

Workhorses sleeping in horse manes of pasture.

Wooden reaper. Walking plow. Hayrick.”4

Or this description of sunbeams shining through stained glass:

“Troughs of sunlight angle into the oratory like green and blue and pink bolts of cloth grandly flung down from the high painted windows.”5

Or this about a nun saying her rosary as she walks outside on a wintry day:

“Each prayer grayly feathering from her mouth.”6

And this:

“Mother Saint-Raphaël stares at Mariette as if she has become an intricate sentence no one can understand.”7

Reading Hansen’s words is like savoring manna.

“Even This I Give You”

In August 1906, seventeen-year-old Mariette becomes a Sisters of the Crucifixion novice, a (fictional) cloistered contemplative order. Her father Claude Baptiste, a worldly physician, is furious at her decision. He’s already lost one daughter, Céline, to God. In fact, Céline is the prioress of Our Lady of Sorrows convent into which Mariette is admitted. Our Lady as well as the Baptiste household is located in Arcadia, a New York village near the Canadian border. Many of its nuns, as well as Père Henri Marriott, the priest who serves as their confessor, are more comfortable in French than English.

Mariette has longed to join her considerably older sister as a Bride of Christ ever since she was a young child. On entering the convent, she immediately impresses everyone with her intensely single-minded devotion and humble demeanor. She spends long hours on her knees in prayer, even during the daily hour set aside for recreation, and faithfully carries out all the tasks assigned by her superiors. As she says to one of her sister novices, she longs to be a saint.8

But there are warning signs that her zeal may rest on an unstable psychological foundation. Her father accuses Mariette of being “too high-strung” for religious life because she’s troubled by “trances, hallucinations, unnatural piety, great extremes of temperament” and “inner wrenchings.”9 Obviously Dr. Baptiste’s motives are suspect; he wants to torpedoe his younger daughter’s choice of God over him. But the accuracy of his worries about her “inner wrenchings” soon becomes apparent.

One of those wrenchings is Mariette’s just-beneath-the-surface sensuality that breaks through again and again during her time at Our Lady of Sorrows. On the morning she enters the convent, while still at home in her own bedroom, she stands looking at her naked image in an upright floor mirror.

“She skeins her chocolate-brown hair. She pouts her mouth. She esteems her full breasts as she has seen men esteem them. She haunts her milk-white skin with her hands.

Even this I give You.”10

Mariette’s blending of sexual and religious passion is further evidenced when, getting out of her civilian clothes upon arriving at the convent, she looks at a painting of Jesus hanging from the wall. “She touched his pink mouth, the pink rend in his side, and then she touched her own mouth. She touched underneath her skirt.”11 Moreover, her presence among the other novices and even some of the older nuns is electric with semi-repressed eroticism. They shyly praise her beauty, stroke her hair, take opportunties to physically touch her or just to be in her company. Mariette, sensing their admiration, can’t help being playing the coquette. Although she won’t admit it, she’s gratified and a bit stimulated by their attention.

Gratiae gratis datae?

A mere two weeks into her novitiate, Mariette begins to sense that Christ is speaking to her personally. When she reports these experiences to Père Henri, he writes them off as the predictable and relatively innocent zeal of a youngster new to the intense regimen of religious life. But it isn’t long before Mariette’s experiences take a dramatic turn that captures his attention.

She becomes fixated on the Christ figure, “all red meat and agony,” which hangs on a crucifix above the bed in her cell.12 She’s pierced with pity, guilt, and longing when she recalls the “blood [that] flowed from [Jesus’] hands and head.”13 During meals in the refectory, while listening to Dame Julian of Norwich’s fourteenth-century Revelations read aloud, she resonates with Julian’s desire to experience “the horrors and terrors of death just as Christ did.”14 Like St. John of the Cross, she begins praying for “naught but suffering and to be despised for Your sake.”15 Pushing the envelope even further, Mariette begins physically harming herself. When caught deliberately scalding her hands in boiling water, she meekly confesses, “I just wanted to hurt.”16

Mariette’s physical penances begin to reflect the sublimated eroticism that colors her religiosity: she wraps jagged wire underneath her breasts as well as just under the place where she touched herself on her first day at the convent.

“Mariette is naked. Moonlight glints along a short passage of tangled wire that is as intricate as a signature, that is taut enough to ingrain itself in the skin underneath her breasts. One upper thigh is blackly streaked with blood that is seeping from the rabbit wire that is tied just below her sex.”17

Still later, while performing in a skit based on the Hebrew Bible’s erotic poem Song of Songs, Mariette takes the part of the woman pining for her sweetheart: “O daughters of Jerusalem, if you should ever find my Beloved, what shall you tell him? That I am sick with love.”18 Emotional pain in the form of achingly unfulfilled love partners with the physical pain of her self-imposed bloody penances with tangled wire.

Mariette’s identity of her body with the Crucified Christ’s, her lovesick longing to share his suffering, clearly a sublimation of her own suppressed sexual yearnings, her adolescent zeal to be a saint, and the entire complex of her “inner wrenchings” ultimately take her to what she desires. Shortly after midnight Christmas Mass, less than half a year after she entered the convent, Mariette is granted the union of love and pain with her Beloved she seeks.

“Mariette in the night of the oratory, intently staring at the crucifix above the high altar, her hands spread wide as if she were nailed just as Christ was.

Blood scribbles down her wrists and ankles and scrawls like red handwriting on the floor.

[…] She holds out her blood-painted hands like a present and she smiles crazily as she says, ‘Oh, look at what Jesus has done to me!’”19

Later, when questioned about her “wounds of Christ”—stigmata—Mariette notes how appropriate it is that they came to her at Christmas. “We give gifts to our family and friends,” she says. “And these are God’s gifts to me.”20 Gratiae gratis datae, responds Père Henri. Favors freely bestowed by God.21

Our Lady in Turmoil

News of the stigmata spreads thoughout the convent and, soon, the entire village of Arcadia. Townspeople who rarely worship in the convent’s chapel now flock to Mass just to catch a glimpse of Mariette. They bring gifts—cakes, fruits, vegetables—and expect blessings, or at least indulgences, in return.

For their part, the nuns quickly form into two groups. Some, particularly the young ones, joyously affirm their belief that a miracle has occurred. Not surprisingly, the erotic undertone shows up in their celebration of Mariette’s stigmata. Sister Hermance, another novice at Our Lady, seizes one of Mariette’s wounded hands and licks the blood oozing from it. “I have tasted you,” she cries. “See? Ever since I first met you, I have loved you more than myself […] You have been a sacrament to me.”22

But other nuns, especially the more senior ones, suspect that Mariette is either an hysteric or a fraud. “I shall never believe in these fantasies,” one of them declares. “We have had entirely too much mysticism here and too little mortification.”23

The trouble is that evidence to decide the issue one way or the other is inconclusive. On the one hand, it’s revealed that Mariette has been reading books from the convent’s library about stigmatic saints.24 Moreover, one of the nuns actually claims she heard Mariette confess that her supposed miracle was a hoax, just a bit of fun that got out of control.25 But on the other, bandages soaked in the blood from Mariette’s wounds inexplicably fill a room with the scent of Easter lilies.26 Additionally, sisters hear Mariette wrestling in the nighttime with what they take to be demons angry about the grace showered upon her. In the morning she appears with dreadful bruises and cuts on her body.27

Mother Saint-Raphaël is right. Mariette has become an intricate sentence no one understands, even though some believe. As Père Henri says about her stigmata, “I don’t believe it’s possible. I do believe it happened.”28

As does Mother Saint-Raphaël, who has replaced Céline as Our Lady of Sorrow’s prioress. Nonetheless, for the sake of preserving the convent’s peace, she decides she must send Mariette away. “Have you any idea how disruptive you’ve been?” she asks her troublesome novice. “You are awakening hollow talk and half-formed opinions that have no place in our priory, and I have no idea why God would be doing this to us. To you.”29

Looking and Waiting

So Mariette returns to her father’s home in Arcadia. Just before she leaves the convent, the stigmata disappears, never to return. “Christ took back the wounds,” she says, but “let me keep the pain.”30 Years pass. She avoids neighbors, cares for her father in his final illness, continues to pray the Daily Office she learned in the convent, and teaches French to local youngsters. In one of her tutorials, after helping a student work through the difference between Qui est-ce and Qu’est-ce— Qui est-ce que vous cherchez? (“Whom are you looking for?”) and Qu’est-ce que vous attendez? (“What are you waiting for?”)—

“‘Très bien,’ Mariette says. And then she holds her hands against her apron as if she’s suddenly in pain. She cringes and hangs there for a long time, and then the hurt subsides.”31

Looking for a whom and waiting for a what. Years earlier, when she’d been at Our Lady of Sorrows only a few days, Mariette learned from the fourteenth-century Book of Privy Counseling “that nothing [should] remain in [one’s] conscious mind save a naked intent stretching out toward God.”32 This is what she’s spent her entire lifetime growing into: a naked intent, looking and waiting for the Beloved. She’s no longer “sick with love,” on fire with the torturous but exhilarating passion of her stigmatic days. Her eros has matured into a quieter longing for union, even though she’s still shot through from time to time with a pain that might be Christ’s own, but is certainly hers.

Inner and Outer Wrenchings

It’s tempting to write Mariette off as an hysterical neurotic, a highly suggestible religious zealot, or a confused adolescent who doesn’t quite know what to do with her sexual energy. This was the conclusion many of the sisters as well as her physician father arrived at, and there’s undeniably some truth to it. Mariette was indeed beset by inner wrenchings, and that’s why, observes Père Henri, “it is often hard to tell whether these things are not just illusions brought on by abnormal sensibilities and neurosis.”33 But there’s more to her than that. As I suggested at the beginning of this essay, Mariette seems to be both a John Baptizer and an overwrought adolescent girl.

No surprise, then, that she was expelled from the convent. The Church as an institution has always had trouble with people like Mariette who—again, Père Henri— “challenge theology, psychology, medicine.”34 Deep passion threatens order and stability; exuberance violates established boundaries; unpredictability upsets routine. The curious scriptural detail of John the lover outrunning Peter the institutionalist to meet Jesus (Jn 20:4) can be read as a veiled warning for institutionalists to beware falling behind in their vigilance. Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, proper ecclesial apparatchik that he is, famously heeds that warning. Like Jesus’ relatives and acquaintances, he finds the Lord’s defiance of convention a kind of madness—perhaps brought on by “abnormal sensibilities and neurosis”?—that jeopardizes the institutional Church.35

But Mariette’s story urges us to rethink all this, and above all to resist over-spiritualizing experiences of God. We’re not disincarnate souls communing telepathetically with Divine Spirit. We’re material creatures prey to all the inner and outer wrenchings born of flesh. Our bodies, our psyches, and our personalities, with all their foibles and weaknesses, are the only conduits to God we have—or, put another way, the only mode of access God has to us. God works with what’s available, be it the body’s libidinal frustration, the psyche’s neurotic confusion of pain with love, the ego’s secret ambition to be holy, or even the cautious temperament’s fear of passionately transgressing boundaries.

It stands to reason, then, that if the material means through which God speaks to us is necessarily imperfect and, at times, downright broken, our reception can be bewilderingly unexpected and even shockingly traumatic to both ourselves and those who observe us. But this isn’t a prima facie reason to deny that divine communication has occurred. As Père Henri wisely observed, God “is never at variance with Himself, only with our meager understanding of Him.”36

Here’s the mystery that Hansen’s novel invites us to consider: perhaps it’s the case that all of our inner and outer wrenchings through which God-messages must be filtered are exactly as they should be. They are, after all, those places where our self-defensive wills and our excuse-making rationalizations are weakest. Could it be that it’s precisely through our wounds that God is best able to speak to us—that we’re most receptive? If so, our brokenness may be our greatest spiritual strength.37

It’s no accident that the middle-aged Mariette, now the sole occupant of her father’s house, meditates on a passage from St. Paul:

“Continually we carry about in our bodies the dying of Jesus, so that in our bodies the life of Jesus may also be revealed.”38

Mariette carries the dying of Jesus in her body, and it’s precisely this wound of love, not prayer card perfection, that makes her both bewildering and saintly. As Céline once said to her,

“You’re my sister, but I don’t understand you. You aren’t understandable. Saints are like that, I think. Elusive. Other. Upsetting.”39

Céline spoke truly. Genuine saints confuse us, disquiet us, and even anger us. They probe Christ’s wounds to touch base with and sanctify their own, and in so doing inspire us to touch ours as well. They help us to realize that each and every one of us carries the wounds of Christ.

They teach us how to look and wait.

###

C.S.Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Collier, 1952), p. 46.

Ron Hansen, Mariette in Ecstasy (New York: HarperPerennial, 1991), p. 15.

Previous installments of the Presence of Grace series:

So, What Exactly is a Catholic Novel? (31 December 2023)

Surge, Urbana?: J.F. Powers’ Morte d’Urban (8 January 2024)

Motes and Planks: Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood (9 February 2024)

A Longing for Something We Can’t Name: A.G. Mojtabai's Thirst (5 March 2024)

The Heart’s Deep Longing: François Mauriac's Vipers' Tangle (27 June 2024)

The Many Faces of God: Shusaku Endo’s Deep River (16 October 2024)

Wounds of Love: Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory (2 February 2025)

Mariette, p. 5.

Ibid., p. 32.

Ibid., p. 139.

Ibid., p. 144.

Ibid., p. 19.

Ibid., p. 31.

Ibid., p. 9. Interestingly, Hansen has Mariette repeat this same erotic self-examination towards the end of the novel (p. 178), when she’s forty years old.

Ibid., p. 16.

Ibid., p. 23.

Ibid., p. 74.

Ibid., p. 40.

Ibid., p. 69.

Ibid., p. 70.

Ibid., p. 103.

Ibid., pp. 84-85.

Ibid., pp.107, 112.

Ibid., p. 126.

Ibid., p. 127.

Ibid., p.121.

Ibid., p. 142.

Ibid., pp. 124-25.

Ibid., p. 153.

Ibid., pp. 121-22.

Ibid., pp. 143, 151-54.

Ibid., p.130.

Ibid., p. 160.

Ibid., pp. 173, 175.

Ibid., p. 177.

Ibid., p. 131.

Ibid., p. 127.

Ibid., p. 149.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, Part II, Book V, Chapter V.

Ibid.

Two other fictional works also play with this possibility: Mark Salzman’s novel Lying Awake (New York: Random, 2000) and John Pielmeier’s play Agnes of God (New York: Plume, 1985). Salzman’s novel is as exquisite as Hansen’s. I hope to include an analysis of it in a future installment of this series.

Ibid., p. 178. The quoted passage is 2 Cor 4:10.

Ibid., p. 92.

Excellent review! Reminds me of David Guterson’s “Our Lady of the Forest.” Wonder if you’ve read it.

As we Ponder the canonized remember young St Augustine's prayer Lord grant me chastity humility and temperance but not yet