“Isaac [is] a kind of absence.” —Marilynne Robinson1

“Isaac will live, but he has not been spared or saved.”—Yoram Hazony2

“Waiting characterizes the life of Isaac.”—Robert D. Sacks3

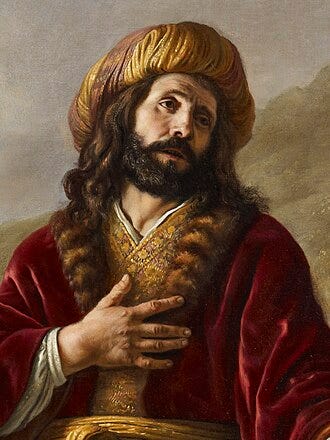

Speculum Jacob

No character in the Book of Genesis—or in the entire Pentateuch, for that matter—comes across more quintessentially human than the Jacob. In fact, we don’t see his like again until David bursts onto the scene in 1 Samuel.

Like so many of us, Jacob is a concidence of opposites: a devious trickster and scoundrel on the one hand and a forthright truthteller and hero on the other. He’s absolutely trustworthy in some regards and utterly faithless in others, lovingly self-giving at times and cynically heartless at others, ravished on at least two occasions by a theophanous vision but more often coldly fixated on wealth and power. He schemes and cheats, regrets doing so, repents of his actions, and then falls into the same cycle again and again. Although his life trajectory suggests some moral growth, the two sides of Jacob remain in conflict until—literally—his dying day.

And yet there’s something about this picaresque man that gestures at the grandeur of being human without whitewashing the weaknesses and failings to which we’re prone.

Jacob, in other words, is a reflection of you and me. He is a mirror, a speculum, an archetypal existential figure whose wayfaring shows us that our flaws need not be fatal and actually may be part of the motley foundation of our virtues. He reminds us of the great truth that although very few of us are saints, even fewer of us are broken through and through. The deeper we plumb his story, surely one of the greatest psychological and spiritual dramas in literature, the more our own interiors are revealed.

This is the first of an eight-part exploration of Everyperson Jacob. It seems more than appropriate to launch it at the beginning of Lent, the holy season in which we’re invited to dive deeply inward—duc in altum!—to discern the deadends, culs-de-sac, and open horizons of our own wayfaring. A prelude of sorts to the entire series, “Did God Really Command Abraham to Sacrifice Isaac?,” may be read here. But it’s not a necessary prolegomenon to the series.

Burdened Before Birth

Let’s begin with Isaac, Jacob’s father. To understand how the father became who he was is already to say something about who his son will be. The path Isaac trod inevitably influenced his son’s.

Isaac was the child of Abraham, the man especially chosen by God to be a junior partner in the post-Flood rebuilding of the divine-human relationship.

“And the LORD said to Abram, ‘Go forth from your land and your birthplace and your father’s house to the land I will show you. And I will make you a great nation and I will bless you and make your name great, and you shall be a blessing […], and all the clans of the earth through you shall be blessed.” (Gen 12:1-3)

Just to make sure there was no doubt about his intentions, God ratified the original summons and covenant-blessing on three separate occasions with the promise to make Abram’s descendants a mighty nation whose inhabitants outnumber the stars (Gen 15:5-6)), to make his name great throughout the ages: “Abraham, Father of Many Nations” (Gen 17:4), and to bestow a universal blessing through him upon “all the nations of the earth” (Gen 22:18). Moreover, God made it clear that the history-changing covenant he struck with Abraham would also include his descendants, especially his as yet unborn son Isaac. (Gen 17-19)

All sons are existentially derivative and dependent on their fathers. They carry seeds of the traits and dispositions that defined their sires, and the names and lineages they inherit fashion to some extent their own self-images. Moreover, in ancient cultures, sons were always expected to honor their fathers, no matter what. That’s one of the reasons why Absalom’s rebellion centuries after Abraham’s time so shattered his father David.

Under normal circumstances, then, sons carry a heavy-enough burden. But to be the son of an extraordinary father—and in Genesis, none is more exalted than Abraham—is to risk a permanent and anxious sense of inadequacy: how can the father’s shoes ever be filled? How can his legacy be honored? As one perceptive commentator puts it, “to be the son of a great father is to be still more subordinate, at risk of being permanently overshadowed, even when one reaches one’s prime.”4

This is Isaac’s burden, decreed for him the moment God singled Abraham out through the covenant blessings. Even before Isaac is conceived, the cards are stacked against him. The ominous words of the psalmist fit him perfectly: “Every one of my days was decreed / before a single one came into being.” (139:16)

Bitter Laughter

So Isaac is locked into a legacy he’ll find impossible to live up to. As the inheritor of his father’s covenant with God, he’ll be charged with continuing Abraham’s great work. But as the son of an extraordinary man, he’ll feel overshadowed and crippled by a sense of his own comparative ordinariness.

It’s as if God is playing a joke on him. Or at least you’d suspect as much from all the background laughter.

It begins with Isaac’s own father-to-be. When God announced to an aged Abraham that his barren wife Sarah will bear a son, he “flung himself on his face and he laughed, saying to himself, ‘To a hundred-year old will a child be born, will ninety-year-old Sarah give birth?’” (Gen 17:17) A bit later, when the three mysterious visitors arive to repeat the prediction of a son, it’s Sarah’s turn to laugh because she was “advanced in years [and] no longer had her woman’s flow.” (Gen 18:11)

There’s more than a hint of scornful disbelief to Abraham’s and Sarah’s response. It’s not the joyful laughter that greets good news, but rather the sardonic eye-rolling snort that dismisses an implausible proposition. Sarah even obliquely admits as much when, confronted by the three visitors who hear her laughing, she defensively denies having done so. Moreover, when Isaac is born, she astoundingly says, “Laughter has God made me / Whoever hears will laugh at me.”5 (Gen 21:6) The same raised-eyebrow cackle of cynical laughter with which she and Abraham greeted the news that Sarah would bear a child will now, she fears, be directed at her by her acquaintances. Imagine a nonagenarian woman giving birth! How ludicrous! How inappropriate!

The Hebrew word for “laughter” is tsehoq. It can also signify “mockery,” and that certainly seems to be the sense in which it’s used in all three of these episodes: Isaac’s conception and birth is greeted with snickering. Even worse, his very name hangs the mockery around his neck. Yitshaq or Isaac means “He laughs,” “He Will Laugh,” or “He Who Laughs.” But who’s doing the laughing? Certainly not Isaac, either the child or the man. The slightest familiarity with his life doesn’t reveal much cause for rejoicing. Could the “He” be divine? Could it be God Who’s laughing at what He knows will be Isaac’s future?

We know nothing about Isaac’s early childhood except for one incident that highlights the mockery that seems to be his fate. Although he’s Sarah’s only son, Isaac isn’t the only son of his father. An earlier boy, Ishmael, was sired by Abraham off of the slave woman Hagar. The two lads grow up together until “Sarah saw the son of Hagar the Egyptian, whom she had born to Abraham, metsaheq.” (Gen 21:9) Most English translations of this passage render metsaheq as “laughing.” But why would laughing children at play so set Sarah off that she furiously banishes both Hagar and Ishmael to the wilderness? No, it’s more likely that metsaheq should be translated here as “mocking.” Sarah bitterly resents Abraham’s older son, and the sight of him poking fun at hers is too much to tolerate.

Mocking laughter from his parents, from his playmate, and perhaps even from God: this is the background music of Isaac’s wayfaring.

The Trauma of Akedah

Mockery takes a horribly dark turn at some point in Isaac’s youth. He may’ve been a mere lad or he may’ve been twenty or so years old; the biblical record is unclear. But it doesn’t really matter, because what’s indisputable is that what befell Isaac on a mountaintop in the land of Moriah poisoned the rest of his days. It’s as if all the hurtful laughter was a runup to it.

I’m referring, of course, to the Akedah, the binding of Isaac, when God tested Abraham by ordering or asking him to sacrifice Isaac. It’s a biblical tale that’s haunted readers for centuries. Many of them have twisted themselves into knots trying to find arguments to justify a father’s willingness to kill his own child.6

When Abraham and Isaac arrived at an appropriate spot on the mountain,

“Abraham built there an altar and laid out the wood and bound Isaac his son and placed him on the altar on top of the wood. And Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to slaughter his son.” (Gen 22:9-10)

At the last moment, God stayed Abraham’s hand, substituting a ram for the terrified boy. So Isaac’s body survives. But the ordeal causes something in his spirit to crumple and die. As one commentator perceptively observes,

“He is set adrift […] For Abraham the test is over; for Isaac it is just beginning […] At best confusion, at worst dread and anger at his father rule his soul. ‘My father took his knife to me: how could he? Why did he? What did God want of him and of me? What now should all this mean for me?’”7

But the near-sacrifice inflicts more than dread, anger, and confusion. It shatters Isaac’s ability to love and to trust, and the memory of it will steadily erode both his self-respect and his agency.

Before the Akedah, Isaac, like most sons, loved and trusted his father. Only that can explain his curious passivity throughout the whole affair. He follows Abraham up the mountain, not pressing him with a chorus of questions. Why would he? He’s on an adventure with his dad whom he loves and whom he believes would never harm him.8

Isaac’s passivity prior to his near-sacrifice is born of trust. But afterwards, a new kind of passivity descends upon him: the paralysis of shock, the numbness of betrayal, the stupefaction of realizing that his father had been willing to butcher him as mercilessly as he would an animal. Isaac sees the knife dangling above him, ready to plunge into his throat, and he freezes. There are no shrieks of terror, no sputtering protests, no pleading. Even afterwards, no words are spoken. There’s nothing to be said. Silence is the new norm of their father-son relationship.

I’ve argued elsewhere that because of the Hebrew prefix na’, it’s likely that God asked rather than commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac.9 But if so, the effect on Isaac would’ve been even more devastating. Bad enough if his father obeyed an order coming from the Most High; even worse if he voluntarily complied with a mere request.

So Isaac’s love and trust when it comes to his father are permanently wounded; it’s significant that Abraham comes down from the mountain by himself, without Isaac. (Gen 22:19) The Bible records no more face-to-face interactions between the two, although Isaac does help his half-brother Ishmael bury the old man when he finally dies. (Gen 25:9) To sustain the covenant-chain, Abraham leaves all his possessions to Isaac. (Gen 25:5) But the inheritance must’ve been a bittersweet reminder of the relationship destroyed so many years earlier by the Akedah. He gives me his wealth, but not his love.

It’s not just Isaac’s trust of Abraham that was slain on that altar. Another casualty was his trust in God. How could it be otherwise? Already insecure from the awareness that his very name was a sign of divine mockery, his trust in God suffers an excruciating blow after he learns that his ordeal was divinely commanded. A haunting passage suggests Isaac’s post-Akedah relationship with the Divine. As a grown man, his son Jacob will speak of the “God of Abraham and the Terror [pachad] of Isaac.” (Gen 31:52) In a split second on Mount Moriah, God ceased being for Isaac a benevolent deity and became a Pachad, an unpredictable, unfathomable, and utterly frightening Surd of Dread.

Finally, along with the shattering of loving trust in both his father and his God, another victim of the Akedah is Isaac’s sense of self. He must’ve spent many days over the course of his lifetime recalling the terrible event on Mount Moriah, asking himself over and over why he hadn’t resisted, why he didn’t at least scream in protest as his father hogtied him to be slaughtered. And with each stomach-churning self-examination, he most likely came up with only two equally unpleasant possibilities: he was either a fool or a coward, too stupid to realize what was going on or too paralyzed with fear to fight back. Either way, he was a worm and no man.

Sarah’s Tent, Abraham’s Wells

Moral and spiritual weakness will be Isaac’s lot for the rest of his days. In a fundamental sense, he will always remain bound, spiritually hamstrung by his father and by God. As scholar Abraham Julius notes,

“His behavior is conditioned by the binding; he cannot unbind himself. Hence there is an irreversible depletion of life energy, of vitality. He never finds peace—only its counterfeit, peaceful sloth. His actions are muffled and vague; he attempts no experiments, nor does he create any new forms; he gives the impression of being a nonentity.”10

Isaac remains unwed until his fortieth year. One imagines him uncertain, hesitant, conflicted, when it comes to assuming the responsibilities of fatherhood. For him, it’s a role forever associated with betrayal and danger. Finally Abraham, clearly impatient with his son’s unmarried state—after all, the covenant-chain depends upon Isaac producing a son—dispatches one of his servants to Laban, his cousin and brother-in-law, in search of a bride from his clan. (Gen 24:2-5) It’s not clear from the text if Abraham even bothers to let Isaac in on what he’s done, suggesting that the estrangement between them is now unbridgeable.

Perhaps that’s why Abraham sends a proxy. But it might’ve also been because he knew that his son, as Marilynne Robinson puts it, is “unprepossessing” and hence unlikely to impress potential wives.11 Did Abraham recognize that he’d irremediably damaged his own son, that he’d so shaken his self-confidence that Isaac was incapable of pulling off a courtship on his own steam?

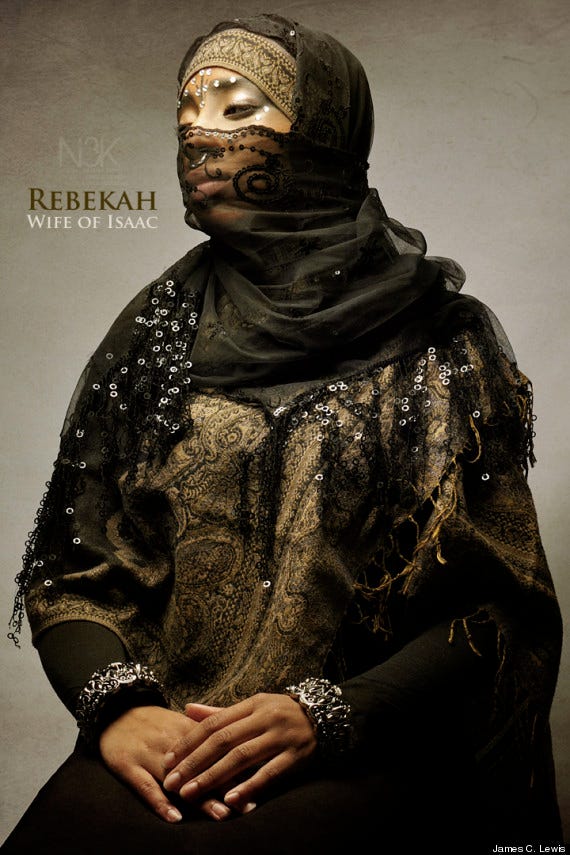

Whatever the reason, the servant goes in Isaac’s place and returns with Rebekah, Laban’s sister, as the bride-to-be. She’s everything that Isaac is not: energetic, assertive, bold, and utterly unmockable. Rebekah would never have remained silently passive had she been on that Moriah altar with Abraham’s knife dangling over her. She’d have resisted with might and main. She didn’t have it in her to be a victim, nor to sympathize with one.

What must this strong woman have thought when she meets unprepossessing, diffident Isaac for the first time? There’s no reason to suppose she was overly impressed. On the journey from her homeland to his, Rebekah surely entertained expectations and dreams of what her life would be as Isaac’s wife. But the moment she laid eyes on him, she sensed his constitutional weakness and realized—perhaps with an unexpected surge of triumph?—that she would have to be the stronger partner in their marriage. It would be up to her to guide her pliant husband.

Rebekah’s sense of Isaac’s brokenness was confirmed nearly immediately. We’re told, in a passage as brief as it is revealing, that on their wedding night, “Isaac brought her into the tent of Sarah his deceased mother” and that Rebekah “consoled him after his mother’s death.” (24:67) What a remarkable revelation! It leads us to conclude that Isaac had turned to his mother Sarah for comfort and support after the Akedah soured his relationship with Abraham. We know from her banishment of Hagar and Ismael that Sarah was fiercely protective of Isaac, which could only have encouraged a clingy dependence on her. In choosing to live in Sarah’s tent after her death and bringing Rebekah to it, the message is that he’s found a new mother-protector. Rebekah will be more Sarah than wife to him.

After his marriage, we hear little about Isaac until the fateful day in which his son Jacob, abetted by Rebekah, bamboozles the paternal blessing out of him. (I explore this in Part 2 of the series.) He amasses wealth and uncovers a few sunken wells that his father Abraham had dug in past years. (Gen 26:15-22) But becoming richer is a small achievement for a man who inherits a sizeable fortune from his father, and the well business is only another attestation to the sad fact that Isaac accomplishes nothing he can call his own. He merely turns over a few spades of earth that his father had already dug. He possesses neither the imagination nor energy to be creative or adventurous. Always and forever, he lives in Abraham’s shadow.

The Real Test

Genesis tells the interlinked stories of three patriarchs: Abraham, his son Isaac, and Isaac’s son Jacob. Grandsire and grandson are larger than life, robust in both their appetites and ambitions. Isaac, the middle term connecting them, is strangely lackluster. He comes across as a minor character in his own story, upstaged by Abraham and Jacob. Significantly, he’s the only one of the three patriarchs who never speaks directly with God. On the surface, he seems to be little more than a place holder, and a particularly fragile one at that.

But being a place holder is crucial to the divine plan. In and through Abraham, God inaugurated a new way for humans to relate to the Divine. As a Kierkegaardian “Knight of Faith,” Abraham was up to the task of collaborating with God. But the ultimate success of the new way depended on the covenant-chain being unbroken by Abraham’s descendents. The really crucial test upon which everything hung wasn’t whether Abraham was willing to sacrifice Isaac. It was whether the weak link in the covenant-chain—Isaac—would hold.

“Isaac is the true test of the new way. Can the new way live through a generation which does not have the stature of its founder Abraham? Everything will depend on the test, since Abraham’s virtue was not only the virtue of a private man but also of one who could establish a way that can last. If Isaac fails, Abraham will have failed […] It is therefore important that the biblical author presents Isaac as a somewhat sleepy man and even, ultimately, as a blind old man.”12

Isaac preserved the legacy handed to him by Abraham. But he paid a price: the knife his father threatened him with always dangled above his head. As we’ll see next time, the trauma he absorbed was passed on to his sons. God’s sin against Isaac, if sin it was—the lifelong mockery, the horror of the Akedah, the betrayal of love and trust— inevitably affected the twins Rebekah will carry in her womb.

Next Time:

“Heel-Grabber: Inherited Fear.” Part 2 of the Jacob the Wayfarer Series

###

Marilynne Robinson, Reading Genesis (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024), p. 123.

Yoram Hazony, The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 120.

Robert D. Sacks, The Lion and the Ass: Reading Genesis After Babylon (Sante Fe, NM: Kafir Yaroq Books, 2019), p. 234.

Leon R. Kass, The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 353.

The phrase can also be translated “Whoever hears will laugh with [yitshaq li] me.” This is because the preposition li can mean “to”, “for,” “with,” or “at me.” Given the through line of tsehoq being associated with mockery, though, I think the more benign rendering is less likely.

Kierkegaard’s justification, his “teological suspension of the ethical” in Fear and Trembling, is probably the best known. It’s also the most absurd. Equally absurd, but intentionally so, is Woody Allen’s hilarious take on the Akedah in his sketch “The Scrolls.” Woody Allen, Without Feathers (New York: Warner Books, 1975), pp. 24-28.

Kass, The Beginning of Wisdom, pp. 357, 359

It’s remarkable that Sarah’s reaction to Abraham’s intended sacrifice of their son is absent in the biblical record. Perhaps we’re intended to suppose she didn’t know what was up when father and son left for Moriah. But as Burton Visotzky points out, at least one rabbinic tradition has her cooperating with Abraham at the altar, an action, of course, which would even further devastate Isaac. Here’s what Visotzky says.

“Preachers in the fourth and fifth centuries actually gave Sarah a voice in verse homilies. The voice they gave her is not of a woman who says, ‘I opt out.’ Quite the contrary. it’s a voice neither of the pedestal nor of the gutter. It’s a voice that has Sarah take her place as the mother of faith, as an equal to Abraham. In these verse homilies, Sarah finds out that Abraham is about to go off to sacrifice Isaac. She knows immediately what’s going on. She says, ‘I know you. You’re drunk with God. And if you’re going to do this, I’m going to be an equal partner. I’ll dig up the dirt and make the altar. Let my hair be the binding to tie up Isaac.’” Bill Moyers, Genesis: A Living Conversation (New York: Doubleday, 1996), p. 238.

“Did God Really Command Abraham to Sacrifice Isaac?”, Cassiacum (8 February 2025)

Abraham Julius, Abraham: The First Jew (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2025), p. 152. Julius’ book is masterful, full of brilliant philosophical, psychological, literary, and theological insights. His “peaceful sloth,” by the way, is a reference to Paradise Lost II, 226-227: “…ignoble ease, and peaceful sloth, not peace…”

Robinson, Reading Genesis, p. 129.

Sacks, The Lion and the Ass, p. 234.

Very interesting reading! I think the following sentence has a typo: “He comes across as a minor character in his own story, upstaged by Abraham and Isaac.” Pretty sure you meant to write “Jacob” rather than “Isaac” here. Thanks!