Motes and Planks

Presence of Grace Series: O'Connor's Wise Blood

“If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite. But man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.”1

“And see, no longer blinded by our eyes.”2

I suppose I’ve read Flannery O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood a good half-dozen times. I don’t think it’s because I especially enjoy it. Somehow, that word doesn’t seem to fit the dark and frequently bizarre saga of Hazel Motes, founder and prophet of the Church Without Christ. Thankfully, its grimness is punctuated by some hilarious moments. O’Connor herself characterized Wise Blood as a darkly “comic novel.”3 Like J.F. Powers, whose Morte d’Urban I wrote about in the first installment of this “Presence of Grace” series on Catholic novels, O’Connor has a cracklingly dry sense of humor which lightens even the more grotesque moments in her tale.

Hostile critics have sometimes interpreted these grotesqueries as artistic ineptitude, the fumbles of a young author who confuses psychopathology and spirituality. On this reading, Hazel Motes is a self-loathing masochist whose self-mutilation at novel’s end is evidence of mental illness.4 (Such is clearly John Huston’s take in his disappointing 1979 cinematic rendering of the novel.) But far from being a clumsy craftsperson, O’Connor was a meticulous and reflective author who worked and re-worked Wise Blood. Moreover, she insists that the book is about redemption rather than abnormal psychology.5 If it contains grotesqueries that come across as pathological—and it does—there’s a reason.

“The novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural; and he may well be forced to take ever more violent means to get his vision across to this hostile audience. … [Y]ou have to make your vision apparent by shock—to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.”6

Spiritual Myopia

Speaking of “almost-blind”: clouded vision plays an important role in Wise Blood. The primary character’s name, Hazel (“Haze”) Motes is also a description of his spiritual condition. For reasons we’ll explore soon, he lives in a cloudy haze of anger and denial that distorts his perception. Furiously focused on pointing out the faults of others—the “motes” in their eyes—he notices the “plank” (Matt 7:3-5) in his own only towards the novel’s conclusion.

References to eyes and vision appear often in the book. When we first meet Haze, his eyes are his most noticeable feature: “so deep that they seem almost like passages leading somewhere,” (4) an observation that anticipates the tale’s ending. He carries with him a pair of his dead mother’s spectacles, and occasionally wears them when he reads from her Bible, even though, significantly, he can’t see through them very clearly. When Sabbath Lily, daughter of the flimflam preacher Asa Hawks, meets Haze, she says: “I like his eyes. They don’t look like they see what he’s looking at but they keep on looking.” (56) Hawks, appropriately named because he’s a predator who feeds on human gullibility, pretends to be blind in order to elicit sympathy and donations. At one point he shouts at Haze, “I can see more than you! You got eyes and see not!” (27) And not for nothing, as the story unfolds we encounter a caged bear who has but one eye (64) and a landlady who’s almost totally blind. (68)

Everyone in the novel seems to be suffering to one extent or another from spiritual or moral myopia: the callous prostitute with whom Haze initially hooks up, Asa and another fake evangelist, Hoover Shoats (again appropriately named: with piglike greed he vacuums up donations from naive folks), commodify religion; and the people of Taulkinham, the purgatorial town in which the story’s action takes place, are coarse and mean-spirited: “All they want to do is knock you down. I ain’t never been to such a unfriendly place before.” (23) The unhappy character who thinks Taulkinham so unfriendly is Enoch Emery, more myopic, as we’ll shortly see, than any other figure in the book.

“I don’t believe in anything”

In a novel of some 150,000 words, “guilt” is mentioned only twice, both times in the same paragraph. The first instance refers to the rather garden variety guilt twelve-year-old Haze experiences after witnessing a tawdry burlesque act at a carnival. But that’s quickly replaced, O’Connor tells us, by an awareness of “the nameless unplaced guilt that was in him,” a guilt so overpowering that the youngster fills his shoes with stones in the hope that his pain will “satisfy Him.” (33)

This is a significant scene, because frenzied efforts to rid himself of this “nameless unplaced” burden is what drives Haze throughout most of the novel. His fire-and-brimstone preaching grandfather had shoved down his throat the conviction that he “had been redeemed and Jesus wasn’t going to leave him ever.” (10) But this knowledge weighs young Haze down with a hyper-awareness of his own perpetual capacity for sin and the ever-present judgmental scrutiny of Jesus, both of which he finds unbearable. Far better to get out from under by denying Jesus. To his way of thinking that eliminates the very possibility of sin—after all, how can there be sin once the sin-denouncer is removed from the picture?—and hence no need for redemption. (I think, by the way, that this is a deliberately ironic distortion on O’Connor’s part of St. Paul’s argument in his Letter to the Romans that we can’t help but sin so long as we try to follow the Law. Simply substitute “Jesus” here for “Law.”) For Haze, it’s a short step from a denial of Jesus to a furiously raging nihilism. “Listen,” he declares, “get this: I don’t believe in anything.” (15)

What can we make of the nameless unplaced guilt which so torments Haze that he angrily renounces what he takes to be its source? I suspect that there are at least three interlocking explanations. The first is his own personal sense of depravity, a conviction drummed into him by his Bible-thumping Calvinist grandfather. The second is his awareness, only dimly conscious but viscerally felt, that there’s something broken at the core of humanity, what theologians call original sin. The third is his wartime experience, deftly intimated by O’Connor in three short paragraphs, which apparently leaves him wounded in both body and spirit, haunted by battlefield trauma and guilt.

Little wonder poor Haze tries to get out from under by demolishing both religion and memory. The solution, he thinks, is “to be converted to nothing.” (11)

Church Without Christ

Curiously, however, Haze’s repudiation of Jesus doesn’t seem to bring him the relief he fancied it would. This is indicated by his frequent and rather desperate protests that he’s free. “I don’t have to run from anything because I don’t believe in anything,” he insists at one point. (39) “I AM clean! If Jesus existed, I wouldn’t be clean,” he shouts at another (47). He reminds me of the jilted lover who tries to convince himself that the breakup doesn’t bother him at all.

Then there’s Haze’s bravado embrace of conventionally “sinful” acts simply to demonstrate that, having jettisoned Jesus, he no longer fears sinfulness. “Conscience is a trick,” he says. “It don’t exist though you may think it does, and if you think it does, you had best get it out in the open and hunt it down and kill it, because it’s no more than your face in the mirror is or your shadow behind you.” (84-85)

So Haze proceeds to do just that: to kill conscience. He adopts a mocking, mean-spirited tone when dealing with people who consider themselves Christian. “I reckon you think you been redeemed,” he sneers at a stranger. “If you’ve been redeemed, I wouldn’t want to be.” (6, 7) He takes up with the prostitute Leora Watts and later seduces (or at least so he thinks) Sabbath Lily, the worldly teenage daughter of Asa Hawks. He blasphemes and curses with adolescent-like gusto. But none of these shenanigans really bring him satisfaction, much less joy. They’re all performed out of a clench-jawed sense of perversely defiant duty. As he clinically explains to Leora at their first encounter, “Listen. I come for the usual business” (17)—not “I come for pleasure,” or “companionship,” or even “curiosity.” No. “The usual business.”

But the epitome of Haze’s angry and ultimately joyless defiance is his founding of the Church Without Christ, the gospel of which he proclaims from the hood of his beat-up jalopy to whomever will listen. After all, “If there’s no Christ, there’s no reason to have a set place to [preach] in.” (54) The new Good News he proclaims from this pulpit on four wheels is that “there was no Fall because there was nothing to fall from and no Redemption because there was no Fall and no Judgment because there wasn’t the first two. Nothing matters but that Jesus was a liar.” (54)

Jesus proclaimed himself the way, the truth, and the life. (Jn 14:6) So Hazel, the self-proclaimed priest of nihilism and sworn enemy of that liar Jesus, preaches the opposite. There is no way, and not much of a life either, because there is no truth.

“I preach there are all kinds of truth, your truth and somebody else’s, but behind all of them, there’s only one truth and that is that there’s no truth. No truth behind all truths is what I and this church preach! Where you come from is gone, where you thought you were going to never was there, and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it. Where is there a place for you to be? No place.” (84)

Wire in the Blood

“I’m no goddam preacher,” insists Hazel Motes early on in the novel. (17) But no one believes him. Even before the Church Without Christ, everyone he meets mistakes him for a preacher, partly because of the stiff, black wide-brimmed hat he wears but also because of “a look in [his] face somewheres.” (15) There’s good reason for their evaluation of him. Despite his protests, Haze is more obsessed with the God he claims to reject than most professed Christians. As a frustrated Sabbath Lily revealingly screams at him at one point, “You don’t want nothing but Jesus!” (96)

Why?

I think an answer to this question, and the key to the whole novel as well as its strange title, is something Haze thunders in one of his street sermons to his startled auditors: “What you need is something to take the place of Jesus!” (72)

Let’s be honest. Traditional Christianity, at least in the Northern hemisphere, is on the decline. A growing number of people no longer believe it offers them much of anything on which to hang their hats. But that doesn’t mean that they don’t need what Haze would call a Jesus-substitute. Humans crave a transcendent Source of deep meaning, even when they no longer consciously believe in one. The hunger is always there, sometimes teasing and sometimes tormenting. As O’Connor hauntingly says, it’s like sensing Jesus moving “from tree to tree in the back of [our] mind[s], a wild ragged figure motioning [us] to turn around and come off into the dark, unsure of [our] footing.” (10)

We know that O’Connor was a fan of T.S. Eliot’s poetry. More than one critic has pointed out how often she alludes to “The Wasteland” in Wise Blood.7 But what’s gone unnoticed, so far as I can ascertain, is her homage to a passage from “Burnt Norton,” one of the poems in Eliot’s Four Quartets.

“The trilling wire in the blood

sings below inveterate scars

appeasing long-forgotten wars.”8

The “trilling wire in the blood” which “sings below inveterate scars” such as the ones left by Haze’s burden of guilt, is the human yearning for God. It’s this trill—what the novel’s character Enoch Emery calls “wise blood”—that won’t leave him alone, propelling him Godwards even as he thinks he’s moving in the opposite direction. His proposed Jesus-substitute—the Church Without Christ—inevitably falls short of what his hardwired trill longs for.

Haze ultimately proves salvageable. But the fate of Enoch Emery tragically illustrates what happens when human hunger for the Transcendent becomes irretrievably misdirected. A rather simple-minded youth, Enoch becomes fascinated with a dwarvish mummy in a museum display case, seeing it as a new god, a “new jesus.” (Note that O’Connor writes “jesus” here in lower case.) He eventually steals the mummy, takes it back to his rented room, and places it in a cabinet niche (originally intended for a slop bucket) that he’s turned into a makeshift tabernacle. His wise blood pumping erratically, Enoch worships the miniature idol, “waiting for something to happen, he didn’t know what. He knew something was going to happen and his entire system was waiting on it …. He pictured himself, after it was over, as an entirely new man.” (89)

O’Connor slyly punctures here, I think, the dubious Nietzschean dream of the Übermensch, of “man overcoming man” by renouncing Christianity. In Enoch’s case, the “new man” he becomes is a hideous devolution. By worshipping an idol—a dried-up mummy which, for O’Connor, represents a desiccated humanism that denies the Transcendent—he becomes less than human, dramatically displayed when poor Enoch dons a “hideous and black” gorilla costume and returns, both literally and mentally, to the wild. He becomes an animal, no longer aware of the God-likeness properly his as a human. “It”—note the “it” instead of “he”—“It sat down on the rock …. and stared over the valley at the uneven skyline of city.” Its “god had finally rewarded it.” (102) To worship a false god is to mutate into a caricature of a human being. Such is the unhappy consequence of mishearing what wise blood whispers in our depths.

Redemption

Unlike Enoch, the tireless call of Hazel’s wise blood eventually leads him to God and redemption, although, true to O’Connor’s dictum that the novelist sometimes has to shock to get the audience’s attention, the way he arrives there is brutal. We shouldn’t be surprised that God won’t let him go. His very name, Hazā'ēl in the Hebrew, identifies him as someone whom “God has seen.” God’s watchfulness is like a cloud, “a large blinding white one with curls and a beard” (61), which looms over Haze and reminds us of the divine cloud that guarded the Hebrew children in the wilderness.

Haze’s rebellion against God, his efforts to ignore or at least sublimate the trilling of the wire in his blood, eventually collapses. Towards novel’s end, after his clunker of a car is finally lost to him—a significant moment because, remember, it served as his pulpit—he admits that he has no direction, no purpose, no end. “‘Was you going anywheres?’” he’s asked. “‘No,’ Haze said.” (108) The nihilistic Church Without Christ simply can’t sustain him. He finally acknowledges his fragility, his inability to survive in a Jesus-substitute world, and in doing so acknowledges that his revolt, which he initially thought would liberate him, has actually been an exercise in disguised despair—what tradtional Catholics call a sin against the Holy Ghost.

He blinds himself with lime—a deed that the flimflam preacher Asa Hawks had only pretended to do to himself—and resumes his childhood practice of filling his shoes with stones. Even more shockingly, he wraps barbed wire around his chest. When his bewildered landlady asks him why he’s punishing himself like this, he replies, “to pay. I’m paying.” Paying for what? “I’m not clean.” But what’s the point of burning out his eyes? “If there’s no bottom in your eyes you see more.” (114-116)

The darkness into which Haze plunges himself is surely meant to evoke what John of the Cross called the dark nights of the senses and soul. In the first, the God-seeker is stripped of her attachment to the distractions provided by the senses; in the second, she’s stripped of her comforting fantasies about God. What’s left is a spiritual emptiness, not unlike Haze’s bottomless eye sockets, into which God can enter.

Hazel Motes, described by O’Connor as a Christian malgré lui (2), has finally found his way home. By depriving himself of physical vision, of renouncing his self-protective drive to keep “his two eyes open and his hands always handling the familiar things, his feet on the known track,” he’s opened himself to “the dark where he was not sure of his footing, where he might be walking on the water and not know it and then suddenly know it and drown.” (10) He’s acknowledged the burden of guilt he’d tried to deny, confessed his inability to go it alone and the despair into which he fell, and found the redemption he once refused. As he says shortly before he dies, “I want to go on where I’m going.” (120) He wants to plunge ever deeper into the dark salvific waters of God.

And something else has happened, too. Haze’s example seems to have wrought the beginning of a conversion in Mrs. Flood, his landlady, who initially cares for him in his blindness only for the sake of the government check he receives each month and hands over to her. But as time passes, she becomes more intrigued by her strange lodger. “To her, the blind man had the look of seeing something. His face had a peculiar pushing look, as if it were going forward after something it could just distinguish in the distance.” (110-111). She can’t stop herself from constantly staring into his face, longing “to penetrate the darkness behind it and see for herself what was there.” (117)

By the time Hazel dies, Mrs. Flood has sensed a deep mystery in his condition—the plank in her own eye is beginning to shrink—a mystery that bewilders as well as beckons. Standing before Haze’s corpse, she “leaned closer and closer to his face, …. but she couldn’t see anything.” She feels as if she’s being blocked “at the entrance to something” monumentally important. So she closes her eyes, inviting in the darkness that saved Hazel.

“She sat staring with her eyes shut, into his eyes, and felt as if she had finally got to the beginning of something she couldn’t begin and she saw him moving farther and farther away, farther and farther into the darkness until he was the pinpoint of light.” (120)

“Something she couldn’t begin”: what else could this be, in this context, but grace, offered by God but revealed to the landlady through her strange, tortured, and ultimately holy tenant? The final act of Hazel Motes, the man who God saw, was to set the wise blood in her trilling.

###

Willliam Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (Boston: John Luce & Co., 1906), p. 26.

Rupert Brooke, “Sonnet (Suggested by some of the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research),” in The Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1931), p. 136.

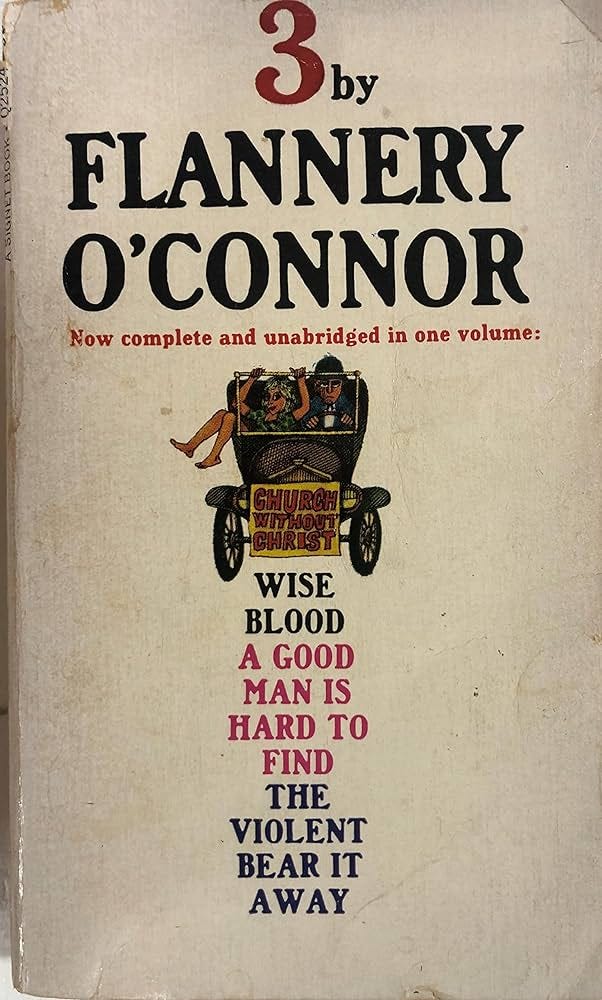

Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood in Three by Flannery O’Connor (New York: New American Library, 1980), p. 2. This is from a short tenth anniversay preface to the novel. Subsequent page references to Wise Blood are noted parenthetically in the text.

One of the most notorious of these takedowns is Ben Satterfield’s “Wise Blood, Artistic Anemia, and the Hemorrhaging of O’Connor Criticism,” Studies in American Fiction 17 (1989): 33-50. Satterfield claims to take a neutral “literary point of view,” but it’s clear he’s disdainful of any religious interpretation of O’Connor’s work—a remarkable position given O’Connor’s deep faith. Jonathan Witt methodically and brilliantly responds to Satterfield and like-minded critics in his “Wise Blood and the Irony of Redemption.” The Flannery O’Connor Bulletin 22 (1993-94):12-24.

In one of her letters, O’Connor writes that Wise Blood “is entirely Redemption-centered in thought. Not too many people are willing to see this, and perhaps it is hard to see because H. Motes is such an admirable nihilist. His nihilism leads him back to the fact of his Redemption, however, which is what he would have liked so much to get away from.” Sally Fitzgerald (ed), The Habit of Being: The Letters of Flannery O’Connor (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988), p. 70.

Flannery O’Connor, “The Fiction Writer & His Country,” in Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, ed. Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1970), p. 34.

See, for example, James McWilliams’ excellent “Escaping the Waste Land: On Flannery O’Connor and T.S. Eliot.” The Millions (27 March 2017).

T.S. Eliot, “Burnt Norton II,” Four Quartets (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1971), p. 15.

Thank you a hundredfold for this! Wise Blood was the novel that gave me an important insight into the act of writing. I often wonder if the book business can do (or does) "re-dos". Like pop songs get remixed a bit and reintroduced to a new generation and now we're all singing "here comes the rain again" again. I don't know what the current generation reads. Is it O'Connor (other than in high school, if at all)?