“. . . punishing the children for the sin of the parents . . .” Deut 5:9

“Intergenerational Trauma: the transmission of trauma or its legacy, in the form of a psychological consequence of an injury or attack, poverty, and so forth, from the generation experiencing the trauma to subsequent generations. The transference of this effect is believed to be epigenetic.”1

There are two famous heels in Western literature. The one everyone’s heard about belongs to the Greek hero Achilles. According to legend, his mother Thetis dipped him in the river Styx to make him invulnerable to wounds. But she made the fatal mistake of holding him by the heel, which remained unprotected: a weakness Paris of Troy later capitalized on.2

So Achilles’ heel became a symbol of mortal weakness.

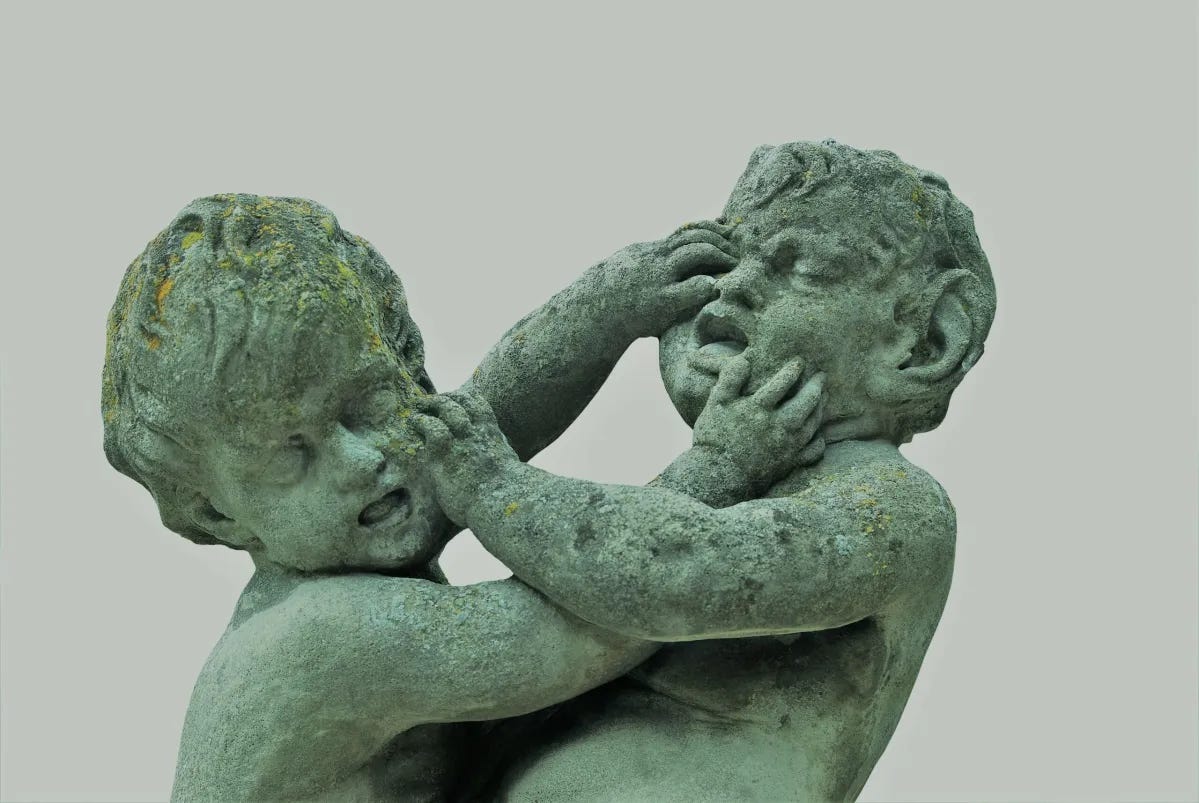

The other lesser known heel is associated with Jacob, the last patriarch in the Hebrew scriptures and hero of this series. He was the younger twin brother of Esau, and when he emerged from his mother he was clutching Esau’s heel, as if to hold him back. Thus he was named Ya’aqov, a pun on ‘aqev or “heel.” He was the heel-grabber, the would-be usurper of his brother’s patrimony.

The story of Jacob’s natal grasp of the heel symbolizes moral weakness.3

For a good part of his adult life, Jacob will try to grab what isn’t properly his. He’ll do so in large part because he inherits the traumatic sense of fear and inadequacy that crippled his father Isaac. But while Isaac’s trauma bred in him a frustrating passivity,4 Jacob’s translates into a compensatory urge to seize by hook or crook whatever he believes would make him invulnerable.

Irremediably psychologically and spiritually wounded by his near-sacrifice on Mount Moriah, Isaac retreats into himself, ever afterwards avoiding his father Abraham (no conversation between the two is recorded in Genesis after the Akedah), anxiously conscious of the seeming whimsicality of Yahweh, whom he now thinks of as the “Fear of Isaac” (Gen 31:42), clings to his mother (when he marries Rebekah, for example, he takes her into the “tent of Sarah his mother,” not the tent of his father [Gen 24:67]), and is apparently unable either to make decisions or strike out on his own. True, he is the inheritor of God’s covenant with Abraham; he is the second biblical patriarch. But his brokenness is apparent.

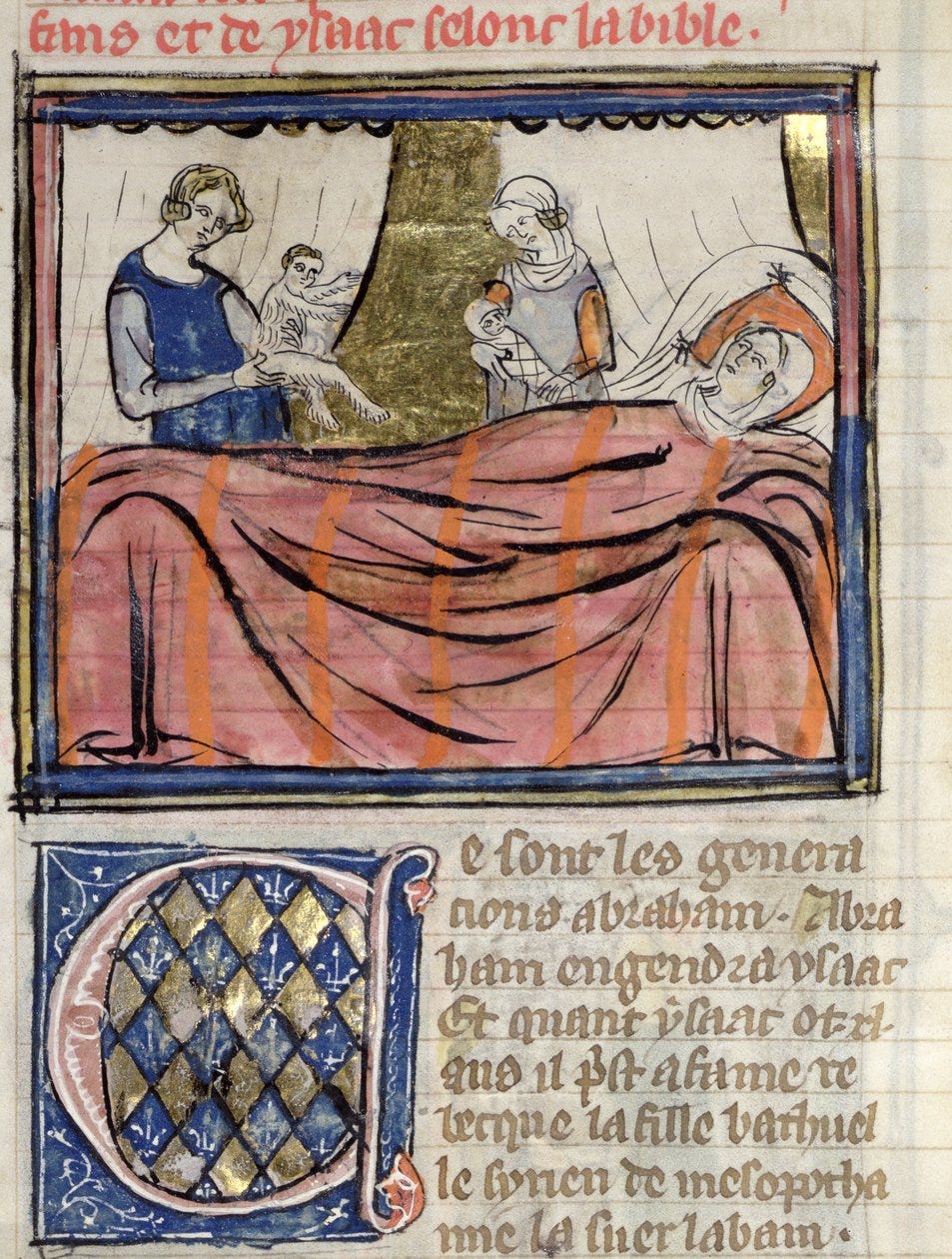

Isaac doesn’t marry until he’s forty years old. Even then, he takes no part in choosing his bride, instead passively accepting Rebekah, the woman selected for him by proxy. Another twenty years pass before Rebekah conceives. (Gen 25:26) We’re told that she’s barren, a familiar trope in Genesis when it comes to the mothers of significant figures, and that she becomes fruitful only after Isaac prays for children. But given everything we know about Isaac’s timidity, more plausible explanations are that it took him two decades to consummate the marriage or that his psycho-spiritual trauma somehow interfered with his fertility.

Intrauterine Strife

Nonetheless, when Rebekah finally does conceive, Isaac must’ve felt a great burden lifted from his shoulders: the covenant passed on to him by Abraham would continue; he would have a son to whom he in turn could bequeath it. But from the very beginning of Rebekah’s pregnancy, there are ominous signs that things are going to be complicated.

In the first place, Rebekah’s pregnancy is hard; she feels the child “struggling” within her womb. (Gen 25:22) The Hebrew verb used here, ratsats, is brutal. It literally means “to crush” or “to break into pieces.” So a desperate Rebekah prays to the Lord for relief. To her astonishment, she’s told that she’s actually carrying two children, and that her physical pain is caused by their mutual wrestling, an intrauterine fraternal struggle that portends a later national one. As God warns Rebekah,

“Two nations are in your womb,

and two peoples, born of you, shall be divided;

the one shall be stronger than the other,

the elder shall serve the younger.”5 (Gen 25:23)

Two immediate points are worth noting here.

First, there’s no response from Isaac to the happy news that he’s sired not one but two sons. After twenty years of childlessness, he’s finally succeeded in producing the next generational link in the covenant with God. You’d expect some gesture of celebration on his part. Instead, what we get is silence: more passivity, suggesting relief at paying his debt to the dreaded Fear of Isaac rather than joy at the birth of a child.

Second, the familiar Old Testament theme of the younger son usurping the elder one is repeated here. The younger Abel’s offering is accepted by God, his elder brother Cain’s rejected. (Gen 4:1,5) Abraham’s first son Ismael is driven away, thereby bestowing priority on the second son Isaac. (gen 21:14-21) Similarly, God announces to Rebekah that her younger twin Jacob will steal his older twin Esau’s blessing.6

At the birthing, sure enough—to underscore the reliability of God’s prediction, the text’s author interjects “Look!” or “Behold!” (hinneh)—twins emerge.

“The first came out red, all his body like a hairy cloak, so they called his name Esau. Afterward his brother came out with his hand grasping Esau’s heel, so his name was called Jacob.” (Gen 25:24-26).7

I suppose it’s anatomically inevitable that twins emerge seriatim rather than simultaneously. But the fact that Jacob is reported to have been born grasping or seizing his elder brother’s heel points to the character he’ll display throughout his early years. Leon Kass explains:

“Jacob arrives trying to prevent Esau from being firstborn, trying to supplant him as first-born, tripping him up or holding him back from behind—not in face-to-face encounter but underhandedly. An even stronger reading would suggest that Jacob is trying to weaken or cripple Esau […] All his life Jacob’s name will announce a grasping, rivalrous, devious, supplanting, and most unbrotherly inclination or nature.”8

Jacob the Follower

But as Kass points out, the name Ya’aqov also can mean “follower” (‘aqevoth). In the most obvious sense, Jacob “follows after” Esau in the birthing process, and so by rights should “follow after” him when it comes to Isaac’s blessing. As things turn out, his name also looks forward: by stealing Esau’s birthright, he takes his elder brother’s place to “follow” in the patriarchal line.

But it’s also arguable that Jacob, at least in his early years, “follows” in Isaac’s mode: he’s passive, content to let his mother Rebekah take the reins of his life. The tersely descriptive passage that connects the account of the twins’ birth to the story of the stolen birthright—a duplicity instigated, as we’ll see in the next installment, by Rebekah—suggests that Jacob is a somewhat pliant momma’s boy, just as Isaac was.

“And the lads grew up, and Esau was a man skilled in hunting, a man of the field, and Jacob was a simple man, a dweller in tents. And Isaac loved Esau for the game that he brought him, but Rebekah loved Jacob.” (Gen 25:27-29)

Esau is a man’s man, an outdoorsman with large appetites who delights in the chase. Isaac prefers him to Jacob, although it’s not likely that the “love” he feels for him goes very deep. Rather pitifully, the old man’s affection for Esau seems to be based on his fondness for fresh meat. This only makes sense: Isaac’s trauma has minimized if not destroyed his ability to love full-heartedly.

Jacob is Rebekah’s favorite. We’re not given an explicit explanation for her affection, but we are told that Jacob prefers tents to the fields. In comparison to his brother, his preferences are more domestic, more “womanly.”

Interestingly, we’re also informed that he’s a “simple man.” The Hebrew word tam (“simple”) gestures at several qualities: innocence, integrity, gentleness, mildness. What are we to make of its ascription to Jacob the trickster, the heel-grabber? Could the text be pointing to the man he’ll eventually become, previewing some potential in him that won’t be actualized for a few more years? Or does tam suggest pliancy: his will is “mild,” and hence easily manipulable? Does tam here reaffirm ‘aqevoth? And is that why Rebekah loves him more than she does Esau: because she can control him? My guess is that this final possibility is the most likely one.

Transgenerational Burden

This is all we know about the two brothers until we’re told the familiar story of crafty Jacob tricking a thick-headed Esau and deceiving a near-blind Isaac. What we’re not given in this bare-bones account is any explanation of why Jacob is built the way he is: why, even before his birth, he struggles to get the jump on his brother Esau.

I suggested earlier that Jacob is compensating for an anxious sense of inadequacy inherited from his traumatized father. This isn’t as conjectural as it may seem. We know that trauma may survive transgenerationally; psychological wounds endured by parents can be passed on to their children.

The most obvious way in which children become infected with their parents’ trauma is through behavioral transmission. Traumatized parents may speak about the events that brutalized them, either openly in front of their children or in situations where children covertly overhear. Absorption of such stories, particularly by pre-adolescent kids, can inflict longlasting psychological distress. Moreover, a traumatized parent may exhibit behaviors—anxiety, nervousness, periods of withdrawal, neediness, deep depression, night terrors, and so on—that over a period of time induce similar tendencies in their children, a phenomenon often called “emotional contagion.”9

It’s impossible not to imagine that Jacob would’ve picked up some of his less savory traits through emotional contagion. In living under the shadow of his distant father he surely would’ve absorbed some of Isaac’s troubled passivity. But behavioral transmission can’t account for Jacob’s intrauterine squabbling or his birth canal heel clutching, both of which suggest typical transgenerational trauma symptoms such as an anxious sense of vulnerability and difficulty with relationships.10

In recent years, researchers have revisited the Lamarckian possibility that some intergenerational trauma just might be biologically inherited. Epigenetic transmissions, as they’re called, are hypothesized as links connecting nature and nurture. The suggestion is that some changes in the chemistry of parents induced by enviromental trauma are inheritable by their children. This inheritance isn’t a change in the DNA code itself, but rather a modification of the chemical tags or markers that ride on DNA.

One representative study examined children born from women who were pregnant during the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Some of the women were so distressed that they subsequently suffered post traumatic distress syndrome (PTDS). Chemical analysis indicated, predictably, that they had low levels of cortisol, a hormone involved in stress response. When their children were born, they also exhibited lower than usual cortisol levels. A biochemical change in the mothers induced by external circumstances was transmitted to their offspring.11

Similar studies suggesting epigenetic inheritance of trauma in offspring of American Civil War POWs, Holocaust survivors, Japanese-American internees, and even mice strengthen the case for the possibility that externally-induced trauma may be biologically transmitted.12 The mechanism of such transfers is still inadequately understood, and there’s some opposition in the scientific community to the epigenetic hypothesis. But evidence for it is mounting.

If epigenesis is a fact, it breathes new life into the old biblical claim that the sins of the parents are visited upon the children. The psychological and hormonal responses triggered in poor Isaac when his father Abraham raised the knife over his head, ones that spiritually crippled him for the rest of his life, are passed on to his son Jacob through both emotional contagion and biological transmission. This inheritance of an anxious sense of vulnerability afflicted him with a tendency towards his father’s passivity, which his mother Rebekah will manipulate, but also encouraged the emergence of compensatory strategies such as trickery and deception.

We’ll explore the iconic crescendo of Jacob’s duplicity in the next installment of this series. But it’s good to be reminded that for all his youthful flaws, Jacob the wayfarer, unlike poor Isaac, eventually overcame them to become Israel, the father of the twelve tribes. But that’s getting ahead of our story.

###

Although the legend of how Achilles’ heel became vulnerable is well known, actual written accounts of it appear quite late. The earliest I know is from Publius Papinius Statius’ first-century unfinished epic Achilleid. The reference is brusque—Statius has Thetis say “at thy birth I fortified thee with the stern waters of Styx” (I, 269-70)—but the popularity of the legend ensured that readers would understand it. Statius, Thebaid V-XII and Achilleid, trans. J.H. Mozley (London: William Heinemann, 1928), Vol. II, p. 529.

I owe this insightful comparison to Amy Gabriel’s “Achilles’ Heel and Jacob the Heel-Grabber: Wrestling with Weakness, Fate, and the Mysterious Divine.” The Biblical Mind (15 September 2020).

For a discussion of Isaac’s Akedah-induced passivity, see “Isaac’s Trauma: The Dangling Knife,” the first installment of the “Jacob the Wayfarer” series. A prologue to the series as a whole is “Did God Really Command Abraham to Slay Isaac?”

Poet and translator Stephen Mitchell surmises that the oracle is a later editorial addition designed to justify Jacob’s swindling Esau out of his rightful blessing. This is an interesting, but so far as I can tell, purely speculative assertion on Mitchell’s part. Bill Moyers, Genesis: A Living Companion (New York: Doubleday, 1996), p. 252.

Other Old Testament accounts of younger sons being privileged include Joseph over his elder brothers (Gen 37:3), Moses over the elder Aaron (Ex 7:7), Gideon over his elder brothers (Judg 6:15), David over his elder brothers (1 Sam 16:13), and Solomon over his elder brothers (1 Chron 28:5).

The name “Esau” seems to be a combination of se’ar = “hairy” and asah = “doer, worker.” But rather unkindly, Midrash Rabbah insists that the name is God’s play on the Hebrew word shaw: “It is for nought (shaw) that I created him in My universe,” alluding to the fact that it’s Jacob, not Esau, who will inherit the blessing. Midrash Rabbah, Genesis II, trans. H. Freedman (London: Soncino Press, 1983), p. 565. Rabbah consistently goes out of its way to vilify Esau and exonerate Jacob. For example, because scripture describes Esau as a skilled hunter/trapper, Rabbah interprets this to mean that Esau was adept at entrapping/deceiving others—a description that far better fits Jacob!

Leon R. Kass, The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 407.

See, for example, Pears K.C., Capaldi D.M. “Intergenerational Transmission of Abuse: A Two-generational Prospective Study of an At-risk Sample.” Child Abuse and Neglect 25/11 (2001): 1439–1461; Borelli, J. L., Smiley, P., Bond, D. K., Buttitta, K. V., DeMeules, M., Perrone, L., Welindt, N., Rasmussen, H. F., & West, J. L. “Parental Anxiety Prospectively Predicts Fearful Children’s Physiological Recovery from Stress.” Child Psychiatry and Human Development 46/5 (2015): 774–785; and Golda S. Ginsburg, Jenn-Yun Tein, & Mark A. Riddle. “Preventing the Onset of Anxiety Disorders in Offspring of Anxious Parents: A Six-Year Follow-up.” Child Psychiatry and Human Development 52/8 (2021): 1-10.

Rachel Yehuda, “How Parents’ Trauma Leaves Biological Traces in Children.” Scientific American 327/1 (2022): 50-55.

Martha Henriques explores these and other epigenetic studies in her “Can the Legacy of Trauma be Passed Down the Generations?” BBC (26 March 2019).