“Dry, dry, dry. Blowing dust. Worst drought in 20 years. Wind will not stop. Continual thirst.”1

In the fall of 1994, Washington University hosted a conference, “The Writer and Religion,” to explore the relationship between religion and literature. Six novelists from around the globe were invited to deliver their opinions. Five proved to be hostile in varying degrees to the possibility that religion had anything positive to offer literature. Only one of the six, A.G. Mojtabai, thought otherwise. In her remarks, she lamented that literature today is “willfully inarticulate to spiritual need,” despite the fact that there is “a religious hunger in our country and in our world so widespread that writers ignore or disdain it at our peril.”2

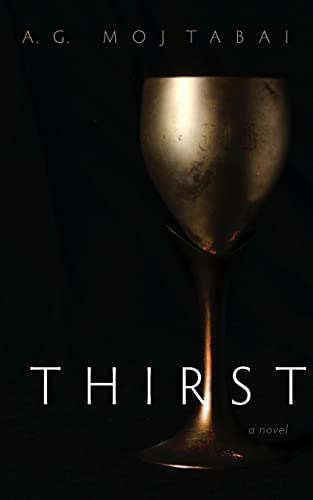

This fourth installment of my Presence of Grace series on Catholic novels3 is devoted to Thirst, Mojtabai’s latest book. Fascinatingly, given both her remarks at the conference as well as the fact that several of her novels, including Thirst, speak sympathetically of religious hunger, Mojtabai is a secular Jew. But she has a feel for the spiritual ethos of Catholicism that would put many cradle Catholics to shame. She’s also an incredible artist who crafts startlingly beautiful sentences like this: “His palate is sculpted like a seabed, his tongue cleaves to it—his mouth is so parched.” (p. 113) And this: “The church is packed, people bending, kneeling, standing, bending in unison, as though a wave washes over them.” (p. 72)

Who is A.G. Mojtabai?

Hers isn’t a well-known name outside of literary circles. She doesn’t have a wide readership; none of her twelve books have been bestsellers. Nor does she go out of her way to seek publicity. An essentially private person, Mojtabai prefers to keep out of the limelight. So it’s helpful, by way of introducing her to a wider audience, to offer a few words about who she is—and I do mean few. There’s not a lot of biographical information (or images of her, for that matter) out there.

Born Ann Grace Alpha in Brooklyn in 1937 (Thirst was published, incredibly, when she was 84 years old!), Mojtabai married an Iranian shortly after her graduation from Antioch College, where she studied philosophy and mathematics. She relocated with her husband first to Iran and then Pakistan, but returned to the States after four years, leaving him behind but keeping her married name.

After earning a couple of graduate degrees, she worked as a librarian at New York’s City College and then lectured for a few years at Harvard. A longtime anti-nuclear activist, she visited Amarillo, Texas, in 1982, intrigued by the apparent incongruence of an über-religious Bible belt city hosting a major factory specializing in death-dealing atomic weapons. Her experiences there resulted in what’s probably her best known book, Blessèd Assurance: At Home with the Atom Bomb in Amarillo (1986).4

To her (and many of her East Coast acquaintances’) surprise, she decided to settle in Amarillo. “I’ve come to love the landscape—prairie and pasture, windmill and grain elevator, a few trees slanted by the wind, and sky, endless sky, which was nothing but an emptiness to me before I learned to look.”5 Between writing her novels, she volunteered for several years at the city’s hospice, a learning-to-look experience reflected in Thirst.

Into the Desert

Thirst’s storyline centers on the dying of an aged priest, Father Theo.6 But he’s not succumbing to a physical illness. Instead, he’s ceased eating and drinking, single-mindedly intent on starving himself to death. His companion in his final days is a slightly younger and recently widowed first cousin, Lena, who’s traveled to Texas from her unspecified East Coast city equally intent on trying to keep him alive. Although raised Catholic, she’s lost her faith and is both mystified and angered by Theo’s resolve to die. At one point, after a visiting nun piously offers the platitude that the dying Theo is going to a better place, Lena impatiently thinks, “There is no better place. This is our only world.” (p. 66) Why, then, she wonders, would Theo abandon it?

On the surface, Theo is killing himself because he’s lost the will to live, which in turn seems to be because he no longer feels a connection with the Divine. Although his days of active parish ministry are over, he serves as chaplain to a nearly empty convent slated for closure. When they gather for meals, the few remaining nuns are “spread out loosely over the long table in the refectory as if to colonize the emptiness.” (p. 2) The emptying-out of the convent parallels Theo’s gradual disappearance of conventional faith. He feels hollowed out by what he’s lost, despairing that nothing is permanent. This gloomy realization prompts a revery about time. He remembers when he visited the ocean and saw glass polished by sand and surf:

“… bits and pieces of once-ordinary bottle glass, abraded by stones and the salt wash of years, but with edges gentled now, incandescent, a frosty radiance at their core. Ordinary glass, slipping back, grain by grain, to the sand from which it was formed, and yet for the time being—a durable now on the human scale—no common stuff, so richly changed.

A durable now . . . . When he longs for permanence, why not think of this?

Isn’t it enough? Why isn’t this enough?” (p. 11)

It clearly isn’t enough, and the emptiness inside him had become so crippling before his retirement that he found himself unable to preach at his final parish Mass. In place of a homily, he had nothing to offer his bewildered parishioners but an anointing. It was as if he hoped the act would somehow reawaken in him a sense of the Holy Spirit’s presence. But when nothing happens, he’s so shaken that, just managing to consecrate the bread and wine, he has to ask his deacon to distribute them. “God has grown dim to me,” he thinks. (p. 75) And so, consequently, has the desire to go on. He has no wish, as he says, “to outlive himself.” (p. 12) Since he feels dead inside, what’s the point of enduring the continuance of his body?

In preparation for his end, Theo begins ridding himself of his few possessions— “shedding pieces of [his] life,” as Lena says (p. 19)—until his rooms are as empty as the nun’s refectory and his own echoey soul. He came naked, he’ll go forth naked. When just about everything is gone but his bed, he enters his house for the final time, lies down, and awaits death. “He will not leave it again.” (p. 12)

The desert fathers and mothers of the third and fourth centuries identified a spiritual malaise they called acedia. It’s a dryness of spirit, a forlorn sense that God has gone dim. It so utterly drains one’s vitality that it was dubbed the “noontide demon” to liken its enervating effects with those of a wiltingly hot day. This sense of spiritual dryness, and the unsatisfied thirst or longing for relief that accompanies it, features prominently in Mojtabai’s tale.

While witnessing with increasing frustration Theo’s final days, Lena discovers one of Theo’s journals. In a string of entries leading up to his decision to not outlive himself, Theo transitions, almost unself-consciously, from recording a drought that’s hit his part of Texas to describing his own parallel interior dryness. His observations are as stark as the spiritual desert he now finds himself in.

“8/23: Hot, dry, wind up again. Pressed by parish council to lead prayers for rain.

8/24: Dry. Tired for no reason.

8/26: Up and doing—dry, dry, dry. Blowing dust. Worst drought in 20 years. Wind will not stop. Continual thirst ….

10/15: Lost my place in the Lectionary this morning ….

12/10: Empty. Death ever before me. Prayer cannot pass through.

12/12: Not a voice not a whisper….

3/2: Terrible longing for something. I have no name for—

3/7: Call it thirst.

God has grown dim to me, a priest.” (pp. 88-89)

A Long Errand into Nothingness?

It’s not as if Theo has been unexpectedly and suddenly tossed into the desert. He’s been wandering around its borders ever since his seminary days. At his Mass exam, when told by his mentor that his rehearsal of the Eucharistic celebration was valid but not particularly fluent, he’d thought to himself, “How could humans, addressing God, ever be sure, ever be fluent?” The question stirred “an unease that never left him.” (p. 77)

The source of that unease seems to be Theo’s awareness that God is inscrutable—as Thomas Aquinas insisted again and again, it’s humanly impossible to comprehend God—and that anything one says about the Divine falls miserably short of the reality. It’s a short step from that realization to either a mystical embrace of the unknowable God or a despairing sense that nothing of what we think we know about God is any more durable than sea glass. Readers sense that throughout his long clerical career, Theo has been able to tamp down his spiritual uneasiness through the bustling and busy life of a parish priest. He’s managed to keep just outside of the full force of the desert’s aridity, even though his fellow priests have always sensed an underlying restlessness in him. As one of them says, “I believe his heart’s torn, somehow.” (p. 26) But now, in his final months, he’s crossed over into the desert’s barren landscape. Dry weather has come to stay.

One of Mojtabai’s most poignant expressions of Theo’s spiritual disorientation is a scene where he pauses before an icon of Mary Undoer of Knots. (On a personal note, this passage is especially moving for me; the parish from which I retired had a special devotion to this aspect of Our Lady.)

“A puzzling painting, he’s always felt …. Mary stands, flanked by angels, serpent writhing underfoot. She is working away at a knotted rope or ribbon; cherubs play with the dangling ends. The problem is, the longer he stares at it, the less clear it becomes whether she’s loosening the knots or creating new ones.” (p. 6)

Perhaps it’s this sense that everything has been called into question that moves Theo to scrawl in his journal this resolve: “Make a list/call it WHAT I STILL BELIEVE.” (p. 107) Revealingly, the list doesn’t get made.

Lena takes to sleeping in a lounge chair in Theo’s living room, alert to any cries for help that might come from his bedroom during the night. Perhaps, she hopes, he may snap out of his madness and decide to live. At one point she’s jolted to attention when she hears him mutter, “Does God see us?” and immediately answers his own question: “Sees us—and watches over us.” But Lena senses something artificially mechanical and pathetically defensive about Theo’s response. She “can’t help noting how he answers himself in smaller voice, a child’s voice, the singsong recitation of a child catechized by rote.” And she thinks, “It’s heartbreaking—to have journeyed so far and still be asking. His life is not—cannot be—an errand into nothingness.” (p. 80)

Into the Silence

But Mojtabai is an author who, knowing full well how complicated humans are, never settles for simple storylines. Theo’s crisis certainly may be read as acedia. That would make Thirst a rather conventional story about a priest who’s lost his faith. But something more subtle may be going on. Theo may be experiencing a crucifixion of the spirit that’s thrusting him into a profound awareness of the God who is beyond words, beyond thought, beyond human doctrine and dogma and definition. As I said earlier, the realization of God’s inscrutability can lead to despair or mysticism. Perhaps in Theo’s case, it leads first to the one and then the other. First, a disorientingly empty nothingness; then, the plenitudinous no-thing-ness, the pregnant silence, of God.

Maybe the hot wind recorded by Theo in his journal is Ruach, which strips only to save.

Lena discovers more jottings in Theo’s journal:

“Papa said ‘I’ve heard enough!’ when he refused hearing aids and chose to remain deaf for the last years of his life …. For my part, I’ve spoken enough.” (pp. 51-52)

Why? In what way has Theo spoken enough—or indeed, as we readers suspect he thinks, too much? Could it be he rejects all his efforts to speak God, in prayer, liturgy, homily, and counseling, as ultimately inadequate? Is he tired of hearing himself speak about God with that clerical in-the-know tone that he undoubtedly assumed as a parish priest, despite his underlying uneasiness?

I suspect that’s part of it. But then Lena finds another of his memos-to-self, this time a haiku-like insight scribbled on a 2x2 Post-It note.

The Word became flesh, became words

Paved over with words. (p. 52)

Speaking about God in the conventional language of the Church, and even of the Bible, risks paving over the vitality of the Word with the cloying cement of words: a new take on St. Paul’s claim that the letter kills while the spirit gives life. This entombment is unintentional, but very real unless we’re alert to the tenuous and troubled relationship between religious language and the living God. For his part, Theo has had enough of burying God in words. Unlike his papa, he wants to listen. But he realizes that this requires that he cease speaking, which means stripping down until there’s nothing left of him to drown out God’s silent voice. And this relinquishment of self, in his case and all cases, is dreadfully painful. It nails us on the Cross with Jesus. Like the Lord, who screamed out his own thirst from the Cross, Theo resists anything that might distract him from his own Golgotha by easing the pain of stripping-down. He rejects the vinegar-soaked sponge, much to Lena’s dismay.

And right before his Passion concludes, something wondrous happens: having renounced everything, even life itself, Theo’s lifelong uneasiness drops away. He’s able to affirm, gently but with absolute finality, his faith as a Christian and his vocation as a priest. Lena, sitting at his bedside, notices that he’s gesturing with his hands, although he’s barely conscious. She soon recognizes what’s going on: he’s distributing Communion.

“His hand mimes the old gestures. Repeatedly, he plucks something from the sheet, raising, and resting it an instant in midair, then into the joined hands of someone standing before him with the gesture of placing a gold coin or gem—something rare and precious—into a cup. Lena knows he’s seeing the distinct faces of individuals because every now and then he extends only his fingertips to place the Host the old-fashioned way, into the open mouth of the person standing before him ….

Feed my flock. Starving himself, he keeps on dishing it out.”7 (pp. 117-18)

Shortly afterwards, Lena hears Theo murmur, “If you’d let me finish,” (p. 125), an immediate reminder of Jesus’ “It is finished” cry from the Cross. And he is allowed to finish, to enter into the mysterious but ultimately fulfilling silence of God for which he yearned. His offering of self has been accepted.

Thirst for Meaning

Mojtabai’s imaginative sensitivity to the complexities of human yearning makes either of these interpretations, despair or submission, perfectly reasonable. Absolute certainty when it comes to faith and absolutely confident disbelief, despite their obvious differences, share a family resemblance: they both avoid the far more difficult path of “terrible longing,” as Theo writes in his journey, “for something [we] have no name for. Call it thirst.”

Shortly after Thirst appeared, Mojtabai, notoriously averse to interviews, nonetheless sat down with her publishers to talk about the novel. At one point she was asked whether she, a secular Jew, felt comfortable writing about a Catholic priest. Her reply is a clear reminder that Theo’s thirsty yearning cuts across sectarian lines, is common to all people, and is one of the links that binds us together.

“As a human being and as a writer, I believe deeply that, if I am attentive enough, nothing human should be alien to me.

I am not a dying priest. But—as an aging person—I know something of what Father Theo knows. I am not a priest, but I can imagine (through a blend of feeling-knowing?) beyond what I have witnessed in glimpses of lives structured around prayer and sacrament. I have taken no vows, yet I know what vocation means. Father Theo’s ‘thirst’ touches on my own times of spiritual aridity, my own search for meaning.

There seems to me nothing inherently wrong in wanting to stretch imaginatively; in fact, it strikes me as obligatory, and possibly the central challenge in writing fiction—an empathic identification with the other.8

Even Lena, the fallen Catholic who desperately wanted to save her cousin from what she regarded as a foolishly self-destructive act, bears witness to the universality of the yearning for something she has no name for. At Theo’s graveside service, the presiding priest rather formulaically says that the departed has “entered into peace. Deep peace.”

“Amen to that, Lena breathes, eyeing the deep pit, her glance darting, slanting towards it and away, to the verge, and away. Amen: may it be so.” (p. 130)

Where is the “away” to which Lena’s attention is drawn? It might be the still and silent region that lies on the far side of desert, words, Cross.

###

A.J. Mojtabai, Thirst (Seattle, WA: Slant Book, 2021). p. 88. Subsequent page references are made parenthetically in the text.

Laurel Shaper Walters, “Writers and Religion on Not-So-Close Terms.” The Christian Science Monitor (31 October 1994).

The first three installments: “So, What Exactly is a ‘Catholic Novel’?”, an introduction to the Presence of Grace series as a whole; “Surge, Urbana?”, on J.F. Powers’ Morte d’Urban; and “Motes and Planks,” on Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood.

While writing this essay, I dug out my old copy of Blessèd Assurance. Thumbing through it, I was amazed at how accurately Mojtabai’s portrayals of Amarillo fundamentalists describe today’s Christian nationalists and Trumpster evangelicals.

Slant Books, “Echoes and Whispers: Q&A with A.G. Mojtabai.” (1 February 2021).

I wonder if Mojtabai is indulging in a mischievous pun with Theo’s name. In describing his spiritual crisis, is she also hinting at a crisis God—Theos—is enduring in an increasingly secular, disbelieving culture?

This scene is reminiscent of Father Quixote’s dying distribution of Communion in Graham Greene’s Monsignor Quixote.

“Echoes and Whispers: Q&A with A.G. Mojtabai.” She goes on to take down, quite correctly in my estimation, the fashionable charge of cultural appropriation leveled at artists who don’t stay in the narrow lanes defined by politics of identity warriors:

“I fail—I refuse—to understand why the effort to cross cultural boundaries is so disparaged. Where are we trending? Should women be confined to writing about women, men about men, gays about gays, blacks about blacks, each group kept to its separate silo?

Calling the effort of crossing cultural boundaries ‘cultural appropriation’ is part of the problem. It whispers ‘misappropriation,’ seizing what does not belong to you.”