Red, Red Stuff: The Color of Tragedy

Jacob the Wayfarer Series, Part 3

“Thou sold’st thy birthright, Esau! for a mess; / Thou shouldst have gotten more, or eaten less.” —Lord Byron1

“Esau did not sell his birthright because he was hungry, but rather, since it had no value to him, he sold it for nothing as if it were nothing.” —Ephrem the Syrian2

The story of Esau’s relinquishment of his birthright to his brother Jacob is told in eight lapidary verses (Gen 25:27-34). Yet embedded within that minimalistic narrative is a tragedy that stretches backwards and forwards, the dismal story of a family that both inherits and transmits wounds. The tale isn’t simply about a feud between twins who don’t particularly like one another, but about what happens when children are denied love by parents preoccupied with their own wounds.

Orphan Sons

We’ve seen in the first two installments of this series that Isaac, the father of Jacob and Esau, never recovered from his near-sacrifice on Mount Moriah, and that his subsequent anxiety was passed on, both behaviorally and transgenetically, to his son Jacob.3

But his elder son Esau was also affected by Isaac’s trauma, and deserves more attention than he typically receives. Too often he’s relegated to a minor role in the Jacob saga, a prop whose main function is to further the story of his younger brother’s wayfaring. Even worse, the later rabbinic tradition writes him off as a coarse if not malign brute. He’s a “thorny bush,” according to Midrash Rabah, too boorish to value his birthright, while his brother is a “fragrant myrtle.”4 Jacob, clever and refined, is destined for greatness. He’s the promising son, Esau the disappointing one.

These sorts of appraisals have become conventional wisdom. But I think we forgo a deep dive into the story of Jacob if we undervalue Esau in this way. I believe that he, like his brother, absorbed the trauma of their father Isaac, not to mention the hostility of their mother Rebekah, and that his subsequent woundedness is a much better explanation for his birthright relinquishment than the ones offered by tradition.

“And Jacob loved Esau …”

From the very beginning, Esau has to contend with his younger brother’s need to assert dominance over him. The struggle erupted even before their birth. When Rebekah was heavy with the twins, she felt them fighting inside her. Given their subsequent history as young men, there’s no reason to doubt that Jacob was the aggressor. Little wonder that at their birth, we find him stubbornly, furiously, snatching at Esau’s heel, trying to pull him back, maneuvering to push ahead of him.

The biblical text goes out of its way to record that Rebekah loved Jacob and Isaac loved Esau (Gen 25:28-29). But this simple statement conceals a darkness: the twins’ parents pick sides in the sibling rivalry and claim exclusive ownership of the son each favors. Isaac refers to Esau as his son (benow), Rebekah calls Jacob her son (benah), but neither speaks of their son (benam).5 This division of parental affection surely only feeds the twins’ competition with one another and complicates their relationship with their parents. No less an early Church figure than St. Ambrose picked up on the corrosive effects of the situation: “From this line of [parental] conduct fraternal hatreds are aroused … Let children be nurtured with a like measure of devotion.”6

So although Genesis assures us “And Isaac loved Esau,” his style of paternal love seems suspect on at least two counts, both of which can be traced back to the emotional and spiritual shellacking he endured on Mount Moriah.

The first giveaway is this: there’s no indication in the text that Isaac bothered to circumcise Esau (or Jacob for that matter). Circumcision is the bodily affirmation of the covenant between God and Abraham. As the firstborn son, Esau was the natural inheritor of that covenant, and so should’ve been circumcised by Isaac, just as years earlier he’d been circumcised by Abraham (Gen 21:4) But the text is suspiciously silent about whether this solemnization of the covenant’s hold on the next generation ever occurred.

Is this an indication of Isaac’s trauma-induced passivity, his anxious avoidance of the God who became for him the “Fear of Isaac” (Gen 31:42) after his near-sacrifice? Is it a sign of Isaac’s indifference to or even repugnance of the legacy left him by Abraham, the father who’d actually threatened to butcher him? Whatever the explanation, the absence of any indication that Esau was circumcised reveals something about the quality of Isaac’s love for him.7

There’s a second red flag when it comes to the nature of Isaac’s love for Esau. The text explicitly says that “Isaac loved Esau for the game that he brought him.” (Gen 25:28)

But the Hebrew in Genesis 25:28 is less genteel than the English translation suggests; it reads that Isaac loved Esau “for the game in his mouth.” As translator Robert Alter points out, it’s not clear how to understand this: does Esau literally place food into his father’s mouth or, more idiomatically, are we meant to think of Esau as a lion-like predator who carries prey home in his mouth?8 Either way, two unhappy conclusions may be drawn. First, Isaac’s “love” for Esau is based on low appetite; had Jacob been the son who brought home tasty game, Isaac undoubtedly would’ve favored him. Second, the fact that Esau either literally or metaphorically feeds his father suggests a role reversal: fathers should feed sons, not the other way around. Like everything else in Isaac’s life, his role as a father is flat, passive, needy but ungiving: scarcely what most of us would consider genuine love.

The tragic upshot is that Esau is a son who doesn’t experience love from either of his parents. Isaac is too emotionally shutdown to offer him genuine paternal love, and Rebekah, as we’ll see shortly, isn’t likely to have shown him much genuine affection either—for no other reason, perhaps, than that he was the favorite of Isaac, a husband whose passivity this strong woman surely came to despise. Nor can Esau turn to his twin for the love his parents are unable to give him. Jacob is his adversary.

Esau is an orphan son. He’s on his own.

“… but Rebekah loved Jacob”

And what of Jacob, the star of the drama? Surely he’s not an orphan son too. Even if we grant that Isaac isn’t capable of loving Esau (or, likely, anyone else), what mother doesn’t love her child, especially after waiting for twenty long years to conceive? (Gen 25:26)

But we need to be cautious, because the text suggests that Rebekah’s relationship with Jacob is just as compromised as Isaac’s is with Esau. Both parents’ “love” of their sons is conditional. Jacob loves Esau so long as his belly is filled with savory meat. And Rebekah? Her love for Jacob depends on his pliancy to her will. In a manner of speaking, Jacob is her meat.

It’s significant that the story of Jacob’s sly bargaining for Esau’s birthright comes immediately after we’re told that Rebekah loves Jacob: it’s as if the Genesis editor is signaling that this iconic episode offers an explanation for why she loves him.

As we’ll explore in Part 4 of this series, Rebekah is instrumental in egging on a rather reluctant Jacob to trick Isaac into giving him the blessing that properly belongs to Esau. (Gen 27) It’s too much to suppose that this was a one-off, spur of the moment prompting on her part. More likely, her plan to bamboozle Isaac and disinherit Esau began simmering much earlier, and included encouraging Jacob to be on the lookout for ways to snatch his elder brother’s birthright. Esau’s hunger for the red red stuff provided a perfect opportunity

Granted: this is speculation. But it’s not without grounding. Rebekah comes across as an admirably self-confident maiden when we meet her in Gen 24. She forthrightly and fearlessly greets Abraham’s servant, sent to vicariously woo her for Isaac, and adventurously leaves her home to marry a complete stranger. During the ensuing long journey, the servant undoubtedly offers her a falsely positive description of Isaac. Rebekah would’ve had plenty of time to fantasize about her husband-to-be, dwelling on what she imagined to be his physical strength and stalwart resolve. After all, he was the grandson of Abraham!

Was she disappointed when she actually met him? Given Isaac’s hangdog, beaten persona, so very different from both her expectations and her own confidently strong personality, she very well could’ve been.9 Over the years, his weakness and passivity—dramatically expressed at one point in their marriage when he cravenly pretends that Rebekah was his sister, fearful “lest the men of the place kill me over Rebekah, for she is comely to look at” (Gen 26:7)—only fed her initial response.10 Shock gave way to contempt for him and, by association, coolness towards the son he favored.

What better way to express her dislike and resentment than humiliating Isaac and disempowering his legitimate heir? And what better instrument to bring about those twin goals than her easily manipulated son Jacob, who already harbors dislike of his brother and resentment towards his distant father? Under Rebekah’s guidance, Jacob will first take the the brother’s birthright and then the father’s blessing.

Yes, indeed. Rebekah “loves” Jacob. But that love is measured against how instrumental he is helping her achieve her end. Her love for him is tool-love.

Jacob is an orphan son too, bereft of the parental love children need and bereft additionally of brotherly love. Like Esau, he’s on his own.

The Bekhorah Relinquishment

At last we come to the crucial “red red stuff” text in which Jacob the Grabber, with (so we can safely infer) Rebekah’s encouragement, snatches the birthright:

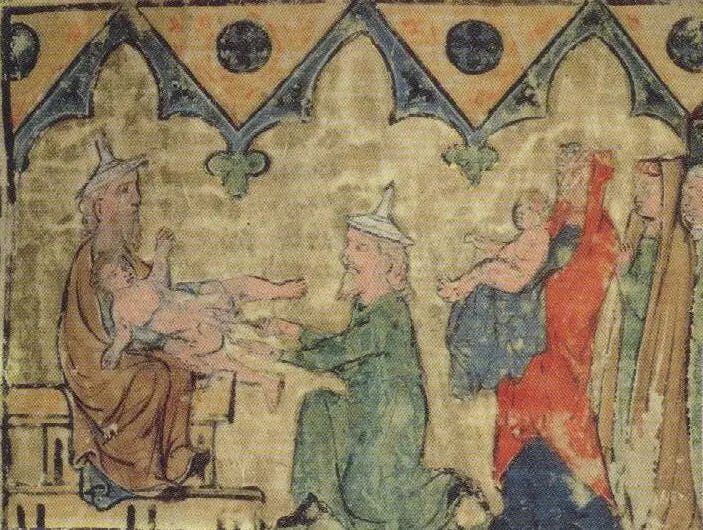

“And Jacob prepared a stew and Esau came from the field, and he was famished. And Esau said to Jacob, ‘Let me gulp down some of this red red stuff, for I am famished.’ Therefore is his name called Edom. And Jacob said, ‘Sell now your birthright to me.’ And Esau said, ‘Look, I am at the point of death, so why do I need a birthright?’ And Jacob said, ‘Swear to me now,’ and he swore to him, and he sold his birthright to Jacob. Then Jacob gave Esau bread and lentil stew, and he ate and he drank and he rose and he went off, and Esau spurned the birthright.” (Gen 25:30-34)

In the Hebraic tradition, the birthright or bekhorah (from bekhor, “the one who comes early”) is the primogeniture right of the firstborn to inherit the father’s wealth. But the boon is also a burden, because along with it comes a heavy load of familial and religious responsibilities. The bekhor knows that he’s a link between the past and the future, charged with honoring ancestors and preparing future generations to carry on the legacy. In the case of Abraham’s descendants, the birthright is especially weighty: eldest sons are expected to receive, honor, and transmit the sacred covenant struck between their family and God.

In the normal course of events, a bekhor would be formed from an early age to take on the responsibility of birthright. The importance of unbroken transmission would be impressed upon him. The story of his ancestors would be drummed into him, so that one day he in turn can repeat it, word for word, to his own firstborn. He would be apprenticed into his future role with love and care and diligence by his father, who in turn was apprenticed by his.

Given the post-Akedah breakdown in the relationship between Abraham and Isaac (Gen 22:19) and Isaac’s distrust and fear of the God who asked for his sacrifice in the first place, it’s hard to imagine that he would’ve been receptive to any bekorah grooming Abraham might have offered. It’s equally difficult to imagine the passive and distant Isaac preparing Esau for his birthright—including, as we’ve already seen, circumcising him.

The usual explanation for Esau so readily trading the bekorah for a bowl of lentil stew is that he was either a coarse halfwit, too stupid to realize what he was doing, or a wicked miscreant, so unworthy of the birthright that God stage-managed the transfer.

The biblical text suggests the first. When Esau begs Jacob to let him “gulp down” some of the stew, the Hebrew is hal’iteni, a word found nowhere else in the Bible. It suggests the way cattle or other livestock—definitely not humans—greedily stuff themselves with food, and its usage here insinuates that Esau is little more than a rapacious animal unable to control his desires. The point is driven home in the text by having Esau desperately demand ha’adom ha’adom hazeh, literally “some of this red red!” His greed is so overpowering that he can’t even finish the sentence with the word “stuff” or “stew” which English translations conveniently provide. Hence, as a signifyng rebuke, his name became Edom or ‘edom, a pun on ha’adom.

The rabbinic tradition plays up the second explanation. In Midrash Rabbah, Esau is condemned as a blasphemer and reviler, a man so perfidious in the eyes of God that Jacob, his pious younger brother, can’t stomach the unholy possibility of Esau being the one who, as the bekhor, offers sacrifice to God. “Said Jacob, ‘Shall this wicked man stand and offer the sacrifices!’ Therefore he [Jacob] strove so ardently to obtain the birthright.” Going beyond even the generously latitudinous boundaries of Midrashic interpretation, one rabbi astoundingly speculates that Esau “brought in with him a company of ruffians who said: ‘We will eat his [Jacob’s] dishes and mock at him’”11—definitely not the kind of behavior you want in an inheritor of God’s covenant.

But given my argument that Esau is an orphan son, I think an alternative pair of possibilities offers more likely explanations for his bekorah relinquishment.

Either (1) Esau doesn’t really appreciate what he’s given up, not because he’s a clod but because Isaac hasn’t adequately schooled him in the birthright’s covenant significance, or (2) he sees how the covenant crippled his father Isaac and wants nothing to do with it lest it break him as well. Esau’s ‘Look, I am at the point of death, so why do I need a birthright?’ doesn’t necessarily suggest, contrary to usual interpretations, an animal-like demand for immediate gratification or deliberate wickedness. Instead, it can be either (1) “Look, what’s the big deal with the bekorah? It’s just a word, barely worth a bowl of lentils. You want it? It’s yours!” or (2) “Look, I’ve only got one life, and life is short. I’m not having it weighed down with the same birthright that broke dad’s spirit. So take it, and good luck with it!”

With neither of these possibilities does Esau deserve our censure. He’s neither stupid nor wicked. He’s a victim of Isaac’s brokenness and Rebekah’s scorn of his father’s weakness. And so is Jacob, although, as we’ve seen, in a different way.

Sacrificial Sons

Every time I re-read this second account of Esau’s and Jacob’s rivalry, (the first being their intrauterine wrestling), I’m struck by how central the color red is to it. Esau is born with a “ruddy” (‘adom) complexion. When he grows into young manhood, he sheds the red blood of animals to satisfy Isaac’s taste for game. The stew Jacob feeds him is obviously made from red lentils since the famished Esau asks for some of the “red red.” Henceforth, because of that life-changing moment as well as his physical ruddiness, he’ll be known as Edom or “Red.” And the nation he’ll found will also be named Edom. Edom was a warrior nation, and red is the color of war. Red, red, red. As the rabbis say, “Esau was red, his food red, his land red, his warriors were red, their gaments were red.”12

Red plays a significant role at various points throughout the Bible. The name of the primordial ancestor, Adam, is “red clay” (‘adom → red) / ‘adamah → earth). On the night of Passover, the Hebrews paint their doorposts red to escape the Angel of Death. (Ex 12:7) Rahab, the Jericho prostitute and ancestor of Jesus,13 lowers a red protective cord from her window. (Jos 2:18) Red fire—the burning bush (Ex 3:2), the wilderness pillar of flame (Ex 13:21)—signals the divine presence. In the Christian dispensation, the Pentecost flames blaze redly. (Acts 2:3) Finally and significantly, red is the color of sacrifice: the blood of sacrificial animals in the Hebrew scriptures, the redemptive blood of the Lamb in the Christian ones.

“The object of all sacred writings,” writes Maurice Nicoll, “is to convey higher meaning and higher knowledge in terms of ordinary knowledge as a starting point.”14 In saying this, Nicoll is doing nothing more than repeating what the Church Fathers, especially those of the Alexandrian School, taught centuries ago. As St. Augustine insisted, there is a spiritual meaning embedded in the most mundane biblical text. The soul’s task is to seek the extraordinary behind the quotidian.15

The fact that redness plays such a starring role in the bekorah relinquishment story suggests that there are at least two deeper truths concealed within it. Both serve as clues to the trajectory of Jacob’s wayfaring, and perhaps to ours as well.

The first is that even though the narrative seems to focus exclusively on an interaction between two brothers, the presence of God—red—saturates their encounter. On the surface, a younger son snatching the elder’s bekorah seems at best unseemly, at worst positively sinful. But underneath the surface, Providence is at work. For whatever reason, God wants the second son to be Isaac’s heir—not necessarily because he’s more worthy than Esau, but simply because this is what God wants.

It’s not, of course, the first time God breaks convention by privileging younger sons over firstborn ones: God favors Abel’s offering over Cain’s, Moses over Aaron, and Joseph, David, and Gideon over their siblings. Who knows why? It simply must be accepted as a teological suspension of the norm, as Kierkegaard might say, but one perpetrated by God rather than a human.

So there’s an Invisible Hand behind what transpires between famished Esau and crafty Jacob. A perfectly ordinary case of sibling oneupsmanship is actually something much more. This same behind-the-scenes providential guidance will be at Jacob’s back for the rest of his journey through life.

But the story’s emphasis on red conceals and yet insinuates another message as well: sacrifice. Esau, Edom, Red, the ruddy one, the brother who gulps down the red red stuff: his birthright is sacrificed in order to further God’s designs. It makes no difference that Esau may not particularly care about its loss. Objectively, something is taken from him that is properly his. This is the surface action, the obvious plot twist.

But underlying it is a more fundamental and fearsome sacrifice: the sacrifice of the two orphan sons’ childhoods. God may’ve stayed Abraham’s hand before he could sacrifice Isaac, but only to demand this double sacrifice. For reasons that are equally unfathomable, God sets in motion a chain of events—the Akedah trauma, Isaac’s broken passivity, Rebekah’s resentful manipulativeness, Jacob’s graspingly insecure temperament, Esau’s endurance of his brother’s rivalry—that imposes suffering on the two boys and, truthfully, on Rebekah and Isaac as well. No one escapes unbloodied. Red sacrifice is splashed across the early chapters of the Jacob saga just as surely as the red presence of divinity.

God and sacrifice: this is the mysterious heart of the red red story. Its inescapable message is that sacrifice is a necessary condition for spiritual growth. No genuine pilgrimage, no authentic wayfaring, no journey towards God and one’s destiny, is purchased cheaply. First the sacrifice, first the tragedy. Then the blessing.

Next Time— Jacob the Wayfarer, Part 4. Who Are You, My Son?: A Stolen Blessing

###

“The Age of Bronze” in The Complete Poetical Works of Lord Byron (New York: Macmillan, 1907), p. 934.

“Commentary on Genesis 23.2” in The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation. Volume 91. Ed. Kathleen McVey (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1994), p. 171.

Prelude: “Did God Really Command Abraham to Sacrifice Isaac?” (8 February 2025)

Part 1: “Isaac’s Trauma: The Dangling Knife” (8 March 2025)

Part 2: “Heel Grabber: The Inherited Fear” (3 May 2025)

Midrash Rabah Genesis. Volume Two. Trans. Rabbi H. Freedman (London: Soncino Press, 1983), p. 565.

In fact, the only time Rebekah and Isaac will “share” a son is when they’re both incensed at Esau taking a Hittite bride. (Gen 26:35)

“Jacob and the Happy Life, 2.2.5” in The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation. Volume 65. Ed. Michael P. McHugh (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1972), p. 149.

I owe this insight to Leon R. Kass, The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), pp. 381-382.

Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible: A Translation and Commentary. Volume 1: The Five Books of Moses (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019), pp. 87-88, ftn. 28.

Rebekah “has expectations she cannot bear to have disappointed, though, I speculate, they have been disappointed since she first saw Isaac walking in that field.” Marilynne Robinson, Reading Genesis (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024), p. 130.

This, of course, is a replay of what Abram did to Sarai when famine drove them into Egypt. (Gen 12:10-20) Family history runs deep.

Midrash Rabah Genesis, pp. 568, 569, 570.

Ibid., p. 568.

I owe this example to my friend and fellow seeker, G. Faris.

Maurice Nicoll, The New Man: An Interpretation of Some Parables and Miracles of Christ (Baltimore, MD: Penguin, 1973), p. 3. Nicoll, a psychologist and student of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, offers insights on scripture that are often refreshingly unconventional.

See, for example, Augustine’s On the Literal Interpretation of Genesis: An Unfinished Book 1.2.5, in The Fathers of the Church: A New Translation. Volume 84. Trans. Roland J. Teske, S.J.(Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1991), p. 147. Teske was one of my graduate professors at Marquette University.