“The Cannibals that each other eat,

the Anthropophagi . . .” —Othello i.iii.166-67

“And yet, for all I see, they are as sick that surfeit with too much as they that starve with nothing.” —Merchant of Venice i.ii.5-7

“Wilt thou whip thine own faults in other men?” —Timon of Athens v.i.39-40

The core message of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice is generally reckoned to be captured in Portia’s gorgeous defense of mercy as an essential complement and occasional antidote to justice. Were it not so, cautions Portia, “in the course of justice none of us / Should see salvation.” (iv.i.205-206)1

Portia’s call to season justice with mercy is an important theme in the play. But its force derives from two frequently overlooked observations about human dynamics in Merchant. From first to last, Shakespeare was a poet who insisted on going beneath the surface to plumb the deepest motives of the human heart, and his probing mind is on full display here.

The first underlying dynamic in Merchant is the human urge to control other persons, particularly those viewed as adversaries or competitors. We’re anthropophagi, intent on consuming or devouring others to make them our own. Certain social contexts, especially those that revolve around commercial transactions and consumerism, unduly encourage our predatory instincts.

This tendency is exemplified by Shylock, the Venetian Jew who, although not the play’s titular merchant, clearly steals the stage. Invited to dine with a Gentile, Shylock accepts. Before departing for the occasion, he says to his daughter Jessica:

But wherefore should I go?

I am not bid for love. They flatter me.

But yet I’ll go in hate, to feed upon

The prodigal Christian. (ii.v.13-16)

The last sentence is cleverly equivocal. Shylock could mean either that he’ll feast at the expense of his Christian host or that he’ll feed on his Christian host—and by implication, on anyone whom he sees and hates as a threat. The second sense is ominous: Shylock’s detestation is so fierce that he’s like a wildly ravenous beast intent on rending enemies, devouring them, digesting them, and then shitting them out, reducing them to the excrement he considers them to be.

The second dynamic is revealed in a curious one-liner from the play’s famous trial scene in Act IV. Antonio, who is the titular merchant, borrows money from Shylock to finance the courtship of his young friend Bassanio, who seeks to win the hand of Portia. The condition Shylock insists on is that Antonio forfeit a pound of his flesh should he default on the loan. When Antonio’s unable to pay, Shylock drags him into court to demand that justice be done. Portia, who by this time has wed Bassanio, shows up at the trial disguised as a learned “doctor of laws” to defend Antonio and disgrace Shylock.

On entering the courtroom, she (disguised as a he, complete with false whiskers) looks at the two men, plaintiff and defendant, and asks, “Which is the merchant here? And which the Jew?” (iv.i.176)

Now, on one level this is a perfectly reasonable question. Portia has never actually met either Shylock or Antonio, and even if she had, her disguise as a visiting advocate requires her to feign ignorance. But it’s also an extremely weird thing to ask, because Jews residing in Venice during the time the Merchant is set were required to wear distinctive red hats, the sixteenth-century equivalent of a yellow Star of David. Shylock would’ve been immediately recognizable as the Jewish plaintiff.

So there must be a reason why Shakespeare puts such an odd question in Portia’s mouth. And there is: it reminds us that many of the characters’ identities, but particularly Shylock’s and Antonio’s, reflect or mirror one another’s. Each could be the other’s doppelgänger. Shakespeare’s point isn’t that human beings are all uniform, but rather that the metaphysical, social, and moral binaries we embrace as static categories—women and men, Jew and Gentile, saint and sinner—are often pharisaic ploys to privilege ourselves. We frequently mirror the very faults we condemn in others. But because we define them as different from us—they’re Jews, we’re Gentiles—we absolve ourselves. We discern neither motes nor planks.

These, then, are the two assumptions about humans that fuel the play: first, that we carry a deep hunger to feed upon and dominate others simply because they’re “other” and therefore threaten us; second, that the borders we fancy distinguish “us” from “them” are often artificial rather than natural, and hence much more porous than we generally allow. If we fail to keep these two fundamental Shakespearean convictions in mind, Portia’s lovely talk about mercy loses much of its force.

Commodification and Consumption

Shakespeare scholar A.D. Nuttal provocatively calls Merchant “Shakespeare’s most Marxist play”2 because it anticipates the claim Marx made famous some three centuries later that economic conditions determine consciousness.3 The play, Nuttal says, is “all about money.”4 Many commentators more or less agree,5 and so do I. But what goes unexplored is the mechanism by which a culture of money mutates the human spirit. It’s too simple merely to chalk it up to conventional greed. This, I think, is what Shakespeare realizes and wants to explore in his play.

It’s appropriate that Merchant’s primary setting is Venice, one of sixteenth-century Europe’s money capitals. Both Shylock and Antonio are products of the city’s ethos: they see everything as having a commercial value; everything for them is a commodity with a negotiable exchange value. Even money itself becomes something to be bought and sold. Jewish usurers like Shylock make “barren metal” or coins “breed” money in the form of interest. (i.iii.135) But Gentile merchants like Antonio likewise breed money from money by investing barren metal in goods which are then sold for a profit. Identity borders are porous.

The commodification mindset inevitably means that all human relationships sooner or later reduce to transactions. Individuals become objects that possess a certain exchange value in the marketplace. Some human commodities (like the play’s Gentiles) are considered rare and expensive bits of merchandise, while others (like Shylock the Jew or the play’s clown Lancelot Gobbo) are cheap and disposable. But all of them can be bought, appropriated, and made one’s own. They can be consumed. They can be ingested.

Images of eating or devouring are scattered throughout the play’s text. Portia’s handmaid Nerissa compares surfeiting and starving and (rather obviously to anyone who isn’t an obsessive consumer) concludes that both are destructive of equilibrium. Shylock, as we’ve seen, proposes to feed on prodigal Christians and carnivorously demands a pound of Antonio’s flesh. In striking the nefarious contract with Antonio, he likens the market value of human to animal flesh. Both are devourable commodities, although “man’s flesh” isn’t “so estimable” as animal’s:

A pound of man’s flesh taken from a man

Is not so estimable, profitable neither,

As flesh of muttons, beefs, or goats. (i.iii.177-179)

When it looks as if Antonio won’t be able to repay the loan, his friend Salarino tries to convince Shylock that the market value of a pound of human flesh is even less than Shylock’s already reckoned it to be. “Why, I am sure if he forfeit,” sputters Salarino, “thou wilt not take his flesh! What’s that good for?” Shylock’s response is revealing: “To bait fish withal; if it will feed nothing else, it will feed my revenge.” (iii.1.50-53) Either way, Antonio is in for it. He’s on the menu. He’s food.

And why does Shylock seek vengeance? Because he loathes Antonio for three reasons: Antonio “is a Christian” who “hates our sacred nation” (i.iii.42,48); Antonio “lends out money gratis and brings down / The rate of usance here with us in Venice” (i.iii.43-44), thereby threatening—or eating into—Shylock’s livelihood; and Antonio has never missed an opportunity to publicly insult and thereby feed upon Shylock:

“Signior Antonio, many a time and oft

In the Rialto you have rated me

About my moneys and my usances.

Still have I borne it with a patient shrug

(For suff’rance is the badge of all our tribe).

You call me misbeliever, cutthroat dog,

And spet upon my Jewish gaberdine.” (i.iii.116-122)

Antonio has bitten Shylock many times; now, by demanding a pound of Antonio’s flesh, he can get his own back. The prey becomes the predator. The consumed becomes the consumer.

But of course the human cannibalistic drive extends beyond the particular hate-driven dynamic between Antonio and Shylock. All of Merchant’s major players are both consumers and commodities, feeders and food; how else can it be in a market-driven ethos? Even romantic partners are no exception; as one commentator astutely observes, “In such a world, there is no incompatibility between money and love.”6 The wooing/consuming of Bassanio and Portia is a case in point.

To his credit, Bassanio is honestly smitten by Portia. But he’s also a fortune hunter. Portia’s fantastically wealthy— “a lady richly left” (i.i.168) by the bequeath of her father—and Bassanio’s a notorious spendthrift who’s perpetually broke and whose troubles will be over if he wins Portia’s hand. To “make her his own,” to use the conventional phrase—to consume her—is to devour her fortune as well. His courtship, then, is an investment in a commodity named Portia that promises huge return. It’s on this expectation that Bassanio borrows a goodly sum from Antonio; he needs money in order to woo Portia in style. (Once again, barren metal is meant to breed.) Antonio, short of ready cash, goes to Shylock for a short-term loan, which results in the unfortunate pound of flesh contract.

Antonio’s willingness to put himself at risk to help Bassanio is almost always interpreted as a lovely altruistic act. As one of Antonio’s friends describes him, “A kinder gentleman treads not the earth.” (ii.viii.37) But there’s a darkness here: Antonio is willingly complicitous in Bassanio’s plan to consume another person; he knows exactly what Bassanio’s intentions are, and he sets the table for Bassiano’s feast.

For her part, Portio is also a consumer. After Bassanio defeats all rivals for her hand—in marketplace competition, a zero-sum victory, absolute dominance, is always the goal—he confesses to her that he’s responsible for the fix Antonio is in with Shylock. Portia immediately gives him more than enough money to pay off the loan. In doing so, as she herself admits, she buys a commodity: Antonio, her beloved Bassiano’s soul semblance.

How little is the cost I have bestowed

In purchasing the semblance of my soul

From out the state of hellish cruelty! (iii.iv.19-21)

Another clever equivocation on Shakespeare’s part: “purchasing” here can simply mean redeeming or rescuing, but also buying-to-own. There’s no “incompatibility between money and love” in a transactional ethos.

A similar dynamic haunts the romance of Jessica, Shylock’s daughter, and Lorenzo, one of Bassanio’s young friends smitten with her. Knowing how fiercely Shylock would oppose a union between his child and a Gentile, the youngsters decide to sneak away together in the dead of night. In leaving, Jessica takes as much of her father’s wealth as she can carry. “Here, catch this casket,” she calls to Lorenzo, tossing down a strongbox of gold ducats from her second floor window. “It is worth the pains.” (ii.vi.34)

Worth whose pains? Surely not Lorenzo’s. He’s strong enough to catch the chest effortlessly. No, the pain is Shylock’s. Jessica reduces her father to nothing more than an ATM, thereby discarding any notion that he might be capable of suffering, and then devours as much of his treasure as she can. Ironically, Lorenzo in turn commodifies Jessica: when he “makes her his own” through marriage, she will become a Christian. “My husband / He hath made me a Christian.” (iii.v.18-19) Lorenzo’s worldview, his faith tradition, consumes hers. Another zero-sum victory.

But a box of gold ducats and gems aren’t the only commodities Shylock has lost. He’s been robbed of another bit of property he thought safe and secure: Jessica, who steals herself from him. Until she broke away, he’d swallowed her identity and controlled her behavior: “Our house is hell,” she laments at one point. (ii.iii.2) After her departure, in a truly pitiable outburst, Shylock laments both money and daughter, intermixing the two as if they’re of the same substance and value—which, of course, in his mind they are.

“My daughter, O my ducats, O my daughter!

Fled with a Christian! O my Christian ducats!

Justice, the law, my ducats, and my daughter!” (ii.viii.15-17)

Commodifying and consuming others is one thing. But Merchant’s characters also self-commodify. They see themselves, like they see everything, as possessing exchange value, a value determined, predictably enough, by how successful they are at consuming others, how much carnivorous energy they exert. It follows that their commodity value—their identity—increases or diminishes in proportion to the lavishness of their diet.

When Antonio believes he’s lost his merchandise-laden ships in a sea storm, for example, he despondently considers himself impotent, incapable of breeding money, and hence worth little more than a rack of mutton or a fallen fruit (both, mind you, viands). I am, he moans,

“a tainted wether of the flock,

Meetest for death. The weakest kind of fruit

Drops earliest to the ground, and so let me.” (iv.i.116-118)

Similarly, when Shylock’s daughter absconds with a goodly portion of his treasure, he despairingly screams,

“…two stones, two rich and precious stones,

Stol’n by my daughter! Justice! Find the girl!

She hath the stones upon her, and the ducats!” (ii.viii.20-22)

“Stones” is a double entendre, signifying both gems and testicles. In losing his two prize viands, ducats and daughter, Shylock’s very manhood has been torn away.

Mirroring

What should be obvious by now is that the characters in Merchant are more alike than unlike. Although they want to believe that they’re distinctively unique and, typically, superior to those “different” from them—Shylock disdains Gentiles as much as Antonio does Jews—they’re really doppelgängers, mirrors of one another. They catch their reflection in each other’s face. The fluidity of their identities undercuts any pretense of absolute polarities that divide the world into in-groups and out-groups. This fluidity is hinted at in the very title of the play: generations of viewers and readers have wondered who actually is the merchant of Venice: Antonio or Shylock?

One of the things Shylock and Antonio mirror in one another is their talent for hating. When asked why he wants a pound of Antonio’s flesh, Shylock snarls out,

“I can give no reason, nor I will not,

More than a lodged hate and a certain loathing

I bear Antonio.” (iv.i.60-62)

Antonio, for his part, makes no attempt to hide his loathing of Shylock. When the Jew confronts him about his public insults, Antonio haughtily replies,

“I am as likely to call thee so [a dog] again,

To spet on thee again, to spurn thee, too.” (i.iii.140-141)

—and this in the very process of asking Shylock for a loan! Antonio will take the Jew’s money, but he won’t acknowledge his humanity.

There are other doppelganger similarities as well. We’ve already seen that both Antonio and Shylock lend money. They also share a penchant for hypocrisy. Antonio accuses Shylock of possessing a deceitfully scheming nature:

“The devil can cite Scripture for his own purpose!

An evil soul producing holy witness

Is like a villain with a smiling cheek!” (i.iii.108-110)

and just a few lines later Shylock levels a similar charge against Antonio:

“O father Abram, what these Christians are,

Whose own hard dealings teaches them suspect

The thoughts of others!” (i.iii.172-173)

Elsewhere, Antonio snarkily says of Shylock: “The Hebrew will turn Christian: he grows kind.” (i.ii.191) And Lancelot Gobbo, servant to Shylock and the play’s resident clown, worries that he’s losing his Gentile identity working for Shylock: “I am a Jew if I serve the Jew any longer.” (ii.ii.111-112) Gentile and Jew risk bleeding into one another.

In the second best known soliloquy from Merchant, Shylock himself breaks down the artificial barriers between Jew and Gentile by insisting that both experience pain and pleasure in the same way, and that consequently both should have recourse to the same remedy against insults:

“If you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge!” (iii.i.65-70)

And in the play’s signature scene, the trial where Portia gets the better of Shylock, she reveals herself as his doppleganger (additionally, her destruction of him is the single most brutal act of cannibalism in the entire play). Throughout the trial, Shylock ceaselessly clamors for justice, fidelity to the letter of the law. The disguised Portia implores him to extend mercy, “an attribute to God himself” (iv.i.201), to Antonio. But when push comes to shove, she reveals herself as merciless as Shylock, humiliating him and impoverishing him, first by threatening his life and then by depriving him of his wealth. She doesn’t in the least exhibit the quality of mercy she condemns him for not extending to Antonio. She becomes Shylock.

In a final display of mirroring, the off-the-hook Gentile Antonio demands of the Jew what Shylock had demanded of him: his life. The pound of flesh, intended to be carved from around Antonio’s heart, would’ve surely physically slain him. But Antonio insists that Shylock be forced to convert to Christianity as part of his comeuppance. In other words, Antonio rips the spiritual heart out of Shylock. He becomes the carver, Shylock the carved viand. The two switch roles, one doppelganger replacing the other. Utterly defeated—utterly consumed—all Shylock can do is crawl away. “I pray you give me leave to go from hence,” he says to the trial’s presider. “I am not well.” (iv.i.412-413)7 He’s worse than unwell. He’s slain and devoured.

There’s one more revelation of mirroring, one more puncture of borders, that deserves mention. During the trial, when Antonio’s supporters denounce Shylock for mercilessly demanding his pound of flesh, he throws their scorn back in their teeth by asserting that they, too, are devourers of human flesh.

“You have among you many a purchased slave,

Which, like your asses and your dogs and mules,

You use in abject and in slavish parts

Because you bought them.” (iv.i.91-94)

He even associates their slaves with “viands” that “season” their “palates.” (iv.i.97-98)

Besides being a rivetingly dramatic retort, I believe this is a fourth wall moment in the play. Shakespeare seeks here to make his audience squirm. Lest they refuse to acknowledge the porosity of the boundary between saint and sinner that Shakespeare has been at pains to show in Merchant, he points the finger at them as members of a society that embraces the practice of human enslavement. You too, he says, are Shylock’s doppelgängers. And of course his finger points at us as well.

Hungry Ghosts

On meeting two of the play’s main characters, we’re immediately told that they’re unhappy, although they have no obvious reason to be. Both are wealthy; both are among the world’s fortunates. Yet Antonio introduces himself as a man bewildered by his own sadness.

“In sooth I know not why I am so sad.

It wearies me, you say it wearies you.

But how I caught it, found it, or came by it,

What stuff ‘tis made of, whereof it is born,

I am to learn.

And such a want-wit sadness makes of me

That I have much ado to know myself.” (i.i.1-7)

Similarly, our first encounter with Portia elicits from her a confession remarkably like Antonio’s:

“By my troth, my little body is aweary of this great world.” (i.ii.1-2)

Shylock never so explicitly enunciates dissatisfaction with life, but his rage to dominate others and his greed for money suggest there’s a great hole in his being. Bassanio’s gold digging and Jessica’s frenetic spending spree after her flight with her father’s money—“Your daughter spent in Genoa, as I heard, one night fourscore ducats,” an acquaintance tells Shylock (iii.1.107-108)—likewise suggest unarticulated alienation.

But why? What’s the source of their discontent?

A page taken from the tantric Buddhist tradition sheds light on their unhappiness.8

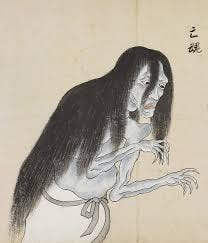

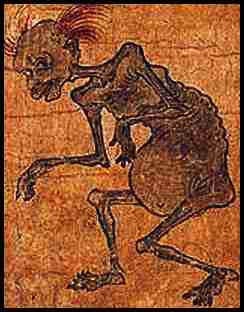

Tibetan Buddhists believe that the cosmos is populated by any number of entities. One of these is a class called “hungry ghosts.” They’re “phantom-like creatures” who are “fusion[s] of rage and desire.” This is because they’re “tormented by unfulfilled cravings and insatiably demanding of impossible satisfactions.” Their appearance is as grotesque as their spiritual state.

“These beings, while impossibly hungry and thirsty, cannot drink or eat without causing themselves terrible pain or indigestion. The very attempts to satisfy themselves cause more pain. Their long, thin throats are so narrow and raw that swallowing produces unbearable burning and irritation. Their bloated bellies are in turn unable to digest nourishment; attempts at gratification only yield a more intense hunger and craving.”9

In the Tibetan worldview, hungry ghosts are both actual entites and metaphors. As actual entities, they’re the spirits of persons who squandered their lives by restlessly demanding more than they could have and refusing to appreciate what was given them. Having fed on everything except what was good for them, they retarded their spiritual growth and forever remain dwarfish and voracious.

As metaphors, hungry ghosts stand for the illegitimate and unfulfillable longings that haunt and frustrate each human being. If the hold of these longings on our heart, mind, and spirit isn’t broken, we become fusions of rage and frustrated desire, forever famished, forever unfulfilled. We become hungry ghosts, unsatisfied by what we devour but unable to stop feeding.

In the culture of commodification and consumption inhabited by Merchant’s characters, the prime directive is to feed on others in an effort either to absorb their substance or erase them as competitors and adversaries. But this rapacity doesn’t provide longterm satisfaction. As Portia’s handmaid wisely points out, surfeiting or gorging is as unfulfilling as starvation. Humans can’t flourish on a diet of human flesh, nor is the hunger for it healthy. It suggests a disordered interiority in which persons have so lost touch with what they truly hunger for that they foolishly and obsessively cram themselves with toxins. And to justify their choice of viands, they tell themselves that what they consume is different from and inferior to themselves, not recognizing—or not allowing themselves to see—that they’re gorging on their doppelgängers.

Scapegoating and the Need for Mercy

There’s an endless and rather tiresome debate about whether or not Merchant is an antisemitic play.10 What’s undeniable, I think, is that Shylock is the scapegoat by which Gentile Venetians exonerate themselves of the very sin for which they damn him.

The Book of Leviticus prescribes a ritual for the annual Day of Atonement that involves two goats, “one marked for the LORD and the other marked for Azazel.” (16:8). The first is sacrificed as an offering to Yahweh; the second is symbolically laden with the sins of the people and driven into the wilderness to wander until it and the community’s collective guilt dies.

In condemning Shylock for his attempted cannibalism of Antonio, stripping him of his fortune, and forcing him to convert to Christianity, Venetian Gentiles designate him as a totem for their own unsavory eating habits and then drive him into the wilderness. Shylock is well aware that he’s being exiled:

“You take my house when you do take the prop

That doth sustain my house; you take my life

When you do take the means whereby I live.” (iv.i. 391-393)

But the supporters of Antonio and Bassanio present witnessing his downfall couldn’t care less. They mock him throughout the trial, exulting in his defeat, enjoying the taste of his blood in their mouths. What other response to a scapegoat loaded with one’s sins could possibly be more appropriate? “Righteous” persons pretend that the transgressions aren’t really theirs by tormenting the poor wretch onto whose shoulders they’ve been placed.

The final act of Merchant, a startlingly abrupt transition from the brutality of the trial to the lived-happier-ever-after marital bliss of Portia and Bassanio and Jessica and Lorenzo, can come across as anticlimactic. But I think it’s Shakespeare’s sly condemnation of a culture that consumes and excludes. None of the characters in this concluding act show even the slightest hint of concern about the utter destruction of Shylock, a fellow human being. Even his daughter Jessica seems indifferent to his fate. Why should they care? As scapegoat, he’s beneath contempt. His only function is to relieve them of the uncomfortable task of self-examination. Once that’s done, they can continue consuming one another with easy consciences.

Now we can fully appreciate why Portia’s speech on the quality of mercy conveys a vitally important message, even though it’s delivered by an unworthy vessel. If, as Shakespeare supposes, we humans are motivated by a lust to consume and dominate others, if we insist on thinking ourselves superior to others and treating them accordingly, if we pretend that we’re faultless by loading our sins on convenient scapegoats, then none of us, as Portia says, can possibly claim innocence before the standard of justice. So, if we’re honest about who we are,

“We do pray for mercy,

And that same prayer doth teach us all to render

The deeds of mercy.” (iv.i. 205-208)

###

This is the latest installment of a series that explores philosophical themes in the Bard’s work. Here are earlier ones:

“What art thou? Speak!”: Bad Faith in Shakespeare's Timon of Athens (22 Sept 2024)

Passing Thoughts on the Henriad (5 Sept 2024)

“Vengeance Rot You All!”: Wild Justice and Law in Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus (14 July 2024)

“...for I must nothing be...”: Disintegration of self and poetic rebirth in Shakespeare's Richard II (14 June 2024)

The Nameless Woe: Shakespeare anticipates Kierkegaard & Co. (10 June 2024)

A.D. Nuttal, Shakespeare the Thinker (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 262.

“The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.” Karl Marx, “Preface,” A Critique of Political Economy, trans. S.W. Ryazanskaya (New York: International Publishers, 1981), pp. 20-21.

Nuttal, Shakespeare the Thinker, p. 255.

For example, W.H. Auden, Lectures on Shakespeare (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), pp. 78-80; Marjorie Garber, Shakespeare After All (New York: Anchor, 2004), p. 284; Natasha Korda, “Dame Usury: Gender, Credit, and (Ac)counting in the Sonnets and The Merchant of Venice.” Shakespeare Quarterly 60 (2009): 129-153; and Laurie E. Maguire, Studying Shakespeare (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004), p. 147. Curiously, the centrality of money isn’t even on Harold Bloom’s radar in his discussion of Merchant in his sometimes tiresome Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (New York: Riverhead, 1998), pp. 171-191.

Mark van Doren, Shakespeare (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1939), p. 79.

Nuttal describes this horrid scene as a “dark symmetry”: “Shylock wanted to tear out the heart of a Christian, and now, at another level, the Christian court wants to tear out the heart of Shylock, his Jewish faith.” Shakespeare the Thinker, p. 261.

The following four paragraphs are adapted from my Godlust: Facing the Demonic, Embracing the Divine (New York: Paulist Press, 1999), pp. 149-150.

Mark Epstein, Thoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective (New York: Basic Books, 1995), p. 28.

In his Shakespeare (p. 171), Bloom insists that the play is “profoundly” antisemitic. On the other hand, Auden’s Lectures (p. 75) insists that “there is no thought of racial discrimination” in it. Regardless of who’s right or wrong in this argument, it’s certainly the case that Shylock, viewed by Elizabethan audiences as a villain through and through, was rehabilitated beginning with Shakespearean actor Edmund Kean’s (1787-1833) sympathetic portrayal of him. That trend has continued to the present day. Harold Bloom (p. 172) huffily deplores such a re-interpretation. “I have never seen The Merchant of Venice staged with Shylock as comic villain, but that is certainly how the play should be performed . . . I am afraid that we tend to make [the play] incoherent by portraying Shylock as being largely sympathetic.”

Long read ... but oh so worth it. You're a good literary analyst, my friend. Great stuff.