“There’s still the river. It’s a deep river, so deep I feel as though it’s for everyone. This river embraces everything about humankind.”1

Shusaku Endo (1923-1996) became known as the “the Graham Greene of Japan,” particularly after the publication of his 1959 novel Silence. Both he and Greene were Catholic converts. Both explored a shared uneasiness with faith in their existentially-themed novels and short stories: Greene because he was never quite able to quell his temperamental skepticism, Endo because he sensed that western Christianity was alien to the Japanese spirit.2

They had something else in common, too: a suspicion that Christianity as a totalizing worldview was pretty much exhausted. Greene believed the western world was increasingly secularized, Endo that orthodox Christianity wasn’t adaptive enough to take root in Asian soil.

Despite their reservations when it came to their personal faith as well as the future of institutional Christianity, Greene and Shusaku believed that the central archetypes of the Christian story—Conversion, Forgiveness, Sacrifice, Resurrection, and Compassion—had such deep metaphysical and psychological roots that they emerge, again and again, even in persons and cultures indifferent to or outright hostile to Christianity. Much of their writing focuses on exploring the various ways in which these archetypes unexpectedly inflect everyday life. Christianity as a religious movement may be on the wane, but for them the symbols that once quickened it endure.

In Endo’s 1993 Deep River, his final novel, he made one last stab at exploring the troubled relationship between Christianity and Japanese culture on the one hand and the tenacity of Christian archetypes on the other. I wouldn’t say that Deep River is a “great” novel. Stylistically, it’s a bit uneven, probably because pieces of it were mined from earlier published short stories. (Endo, who never enjoyed robust health, was quite ill and increasingly weary while writing it.) Even so, his swansong is a haunting parable about the human longing for meaning and redemption that’s well worth reading. That’s why I’ve selected it as the latest installment in my Presence of Grace series on Catholic novels.3

Five Characters in Search of … Something

Endo’s story is about five Japanese in search of something—anything—that will give them a sense of purpose. Most of them aren’t explicitly religious. Only one is a Christian—a priest, in fact—yet all feel a spiritual emptiness that institutional religion historically functioned to fill. But that route is closed to them. They long for transcendence, but not one couched in traditional Christian idiom.

Four of the five—Isobe, Numada, Kiguchi, and Mitsuko—sign up for a tourist excursion to India, eventually winding up in the city of Varanasi, a holy place where thousands of Hindu pilgrims come to die and have their ashes scattered on the sacred river Ganges. There the four will encounter the fifth, Otsu the priest, who lives in an ashram in the city. It’s as if Providence has gently nudged all of them to converge in Varanasi, one of those thin places where heaven and earth draw come close to touching.

The five characters are expressions of Shusaku’s conviction that the pull of Christian archetypes is felt even by nonreligious persons. In Isobe’s case, it’s Resurrection; in Numada’s, Sacrifice; in Kiguchi’s, Forgiveness; in Mitsuko’s, Conversion; and in Otsu’s, Compassion.

The Archetype of Resurrection. Isobe is a typical Japanese salaryman, a rather unimaginative white collar drone, now retired, who devoted more time and energy to his job than to Keiko, his wife. A “taciturn” (p. 11) individual, he only really begins noticing and actually communicating with his wife when she’s stricken with cancer. When she dies, he finds himself horrifed at the prospect of life without her.

“‘Desolation’ would not be the proper word to describe his feelings now; it was more the sense of emptiness he imagined he might feel standing all alone on the surface of the moon.” (p. 16)

In her final moments, Keiko whispers to Isobe that she knows she’ll be reborn, and begs him to search for her. Although he doesn’t really believe in reincarnation—“because he lacked any religious conviction, like most Japanese, death to him meant the extinction of everything” (p. 22)—he feels bound to honor Keiko’s final wish, if for no other reason to atone for ignoring her for so much of their marriage. So when he hears about a child in India who seems to remember a past life as a Japanese woman, he signs up for the tour intending to seek her out.

Isobe eventually discovers that the reincarnated Keiko he sought wasn’t to be found; the child turned out to be a scam. The grief and disorientation he felt at his wife’s death, coupled with his remorse for taking her for granted, erupts in a plaintive cry of anguish as he sits on the bank of the Ganges. “Darling! Where have you gone?” (p. 188) It’s then that the breakthrough realization comes to Isobe, an insight that speaks to his emptiness: in finally recognizing, with a yearning, aching love, just how precious she actually was, Isobe brings Keiko back from the anonymity of nonbeing. She is resurrected, just as she promised she would be. Out of death comes life; from loss, rebirth. Isobe finds what he came to India for. He rediscovers his wife, as well as the bond that united the two of them, and in doing so unconceals his own buried humanity: a second resurrection.

The Archetype of Sacrifice. Numada is a middle-aged author of children’s books, nearly each about animals and the humans who understand their secret languages. In his childhood, Numada was especially fond of two pets, a dog and a hornbill. Early on, he recognizes in himself a “yearning for a connection with every living thing,” (p. 77) especially with creatures. He feels more at home with them than with humans.

As an adult, Numada endures a long illness culminating in a life-threatening operation. Knowing his fondness for animals, his worried wife gifts him with a myna, a magnificent creature to whom he immediately feels bonded. He shares his fears about death, ones he’s unable to confess to his wife, with the bird; the myna in turn shouts out a “ha ha!” (p. 81) which Numada interprets as both a gentle mockery of his anxieties and a call for him to take heart.

The surgery, performed in winter, was touch-and-go. Numada actually briefly dies on the operating table, but manages to pull through. When he awakens from the anesthesia, his wife breaks some bad news to him: his bird companion died while Numada was in surgery. “I wonder,” he thinks, “if it died in place of me?” (p. 82) What begins as a haunting question develops over the years into a conviction: the myna gave itself up to death, sacrificed itself, for Numada’s sake. It willingly perished so that its human comrade might live.

Numada comes to India with plans to release a caged myna into a famous wild bird sanctuary. He considers the gesture a payment of sorts on a longstanding debt. After purchasing a myna from an Indian, he speaks to it as if resuming the conversations he’d carried on with his myna friend years earlier. It’s like the one who died is vibrantly present again—another eruption of the Resurrection archetype, by the way.

When Numada arrives at the sanctuary and whooshes the bird to freedom, he

“felt as though a heavy burden he had carried on his back for many years had been removed. He felt as though he had been able to make a faint gesture of gratitude towards the myna that had died for him that snowy day.” (p. 204)

The ritual of freeing the myna is a gesture of thanks for being snatched from death by the sacrifice of a loving companion. The moment the bird flies away, Numada’s soul thrills to an overwhelming sense of the rich thickness of life, a life salvaged for him by the myna. Standing in the sanctuary, he

“closed his eyes and inhaled the sultry, unripened aroma, like the fermented smell of sake brewing, that emerged from the earth and the trees. The unadorned aroma of life. That life flowed back and forth beween the trees and the chirping of the birds and the wind that slowly set the leaves fluttering.” (p. 204)

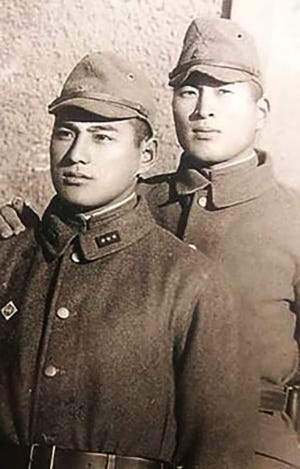

The Archetype of Forgiveness. Kiguchi is a grizzled veteran of World War II who fought and nearly died in the Burma theater. In the desperate retreat along a jungle path that routed Japanese soldiers came to call the Highway of Death, Kiguchi and his comrades fell victim to malaria, starvation, and despair. “We trudged through there like sleep-walkers heading for death.” (p. 85)

The only thing that kept Kiguchi going was the care of his friend and fellow soldier Tsukada. At one point during the retreat, Tsukada offered the weakened Kiguchi some blackened meat. But Kiguchi, “unable to bear the smell, coughed it up again.” (p. 90) Tsukada, however, did eat the meat, which only he knew was carved from one of their fallen comrades. In later years, tortured by the memory of his secret cannibalism and unable to forgive himself, Tsukada takes to drink and eventually dies. Kiguchi, a Buddhist, has come to India to pray for him and their companions who either perished in Burma or who, like Tsukada, survived the war but never really made it out the jungle.

During Tsukada’s final hospital stay, he’s nursed by a western volunteer named Gaston, who only speaks broken Japanese. Gaston is clearly a Catholic—he crosses himself before eating—and in a conversation with him Tsukada expresses astonishment and mild contempt that anyone could possibly believe in God.

“Where is he, then? If he’s there, show him to me.”

“Ye-es. Inside Mr. Tsukada.”

“In my heart, you mean?”

“Ye-es.”

“I don’t get it. How can anybody today claim to believe anything so foolish? Why, we’ve got rockets flying to the moon!” (p. 99)

Shortly before he dies, Tsukada begins hemorrhaging and weakly calls for Gaston, insisting that he has to ask him something. Despite his mockery of it, something about the young man’s innocent faith has moved him. When Gaston arrives, Tsukada brokenly confesses what happened on the Highway of Death.

“I … during the war … I did something horrible. It hurts me to remember it. Very much.”

“Is OK. OK.”

“No matter how horrible?”

“Ye-es.” (p. 101)

Gaston tells Tsukada about the Argentine plane crash in the Andes whose survivors, desperately awaiting rescue from the snowy mountaintop on which they were stranded, resorted to cannibalism to survive. “When these people come back from Andes alive,” Gaston tells Tsukada, “everyone very happy. Families of dead people also very happy. No one angry with them for eating people’s flesh.” (p. 102) They were forgiven; Gaston’s message to Tsukada is that he too is forgiven. He ate to survive. No malice was involved.4

Gaston kneels at Tsukada’s bedside until he died some hours later. He looked like a “bent nail, and the bent nail struggled to become one with the controtions of Tsukada’s mind, and to suffer along with Tsukada.” (p. 103) When Tsukada died, peacefully, his wife believed it was because “Gaston had soaked up all the anguish” (p. 103) in her husband’s heart by assuring him of forgiveness. She wanted to thank the strange westerner for what he’d done. But he was nowhere to be found, and the other nurses had no idea where he’d gone.

The Archetype of Conversion. When we meet Mitsuko, she’s a student of French literature at a Catholic university in Japan. It’s a strange place for her to be: she has nothing but contempt, an “instinctive revulsion,” (p. 38) for Christians and what she interprets as their holier-than-thou superstition. So she delights in shocking them by playing the rebel: drinking, smoking, partying excessively, and mocking everything and everyone associated with Christianity,

When Mitsuko encounters Otsu, an intensely devout student who wants to be a priest, she resolves to “drag him down the path of degradation” (p. 36) as a way of getting back at a faith she despises. Her campaign succeeds. After seducing Otsu she brutally casts him aside, leaving him hurt and confused. Yet her sense of victory is short-lived; afterwards she experiences “a hollowness in her heart.” (p. 35)

After graduation, Mitsuko enters into a loveless marriage. When she and her husband honeymoon in Paris, she learns that Otsu is a seminarian in Lyon and finds herself drawn to see him again despite her disdain for Christianity. “Along with her revulsion, she sensed the existence of some inexplicable thread, something invisible to the eye that had bound her to Otsu.” (p. 43) Although she’s confused about what she wants from him, her hope is that he can help her “search out the darkness in her own heart” (p. 58) by helping her learn to love. So he travels to Lyon, leaving her husband behind in Paris. But her meeting with Otsu is unsatisfying. She wearily complains that he blabbers on about God as tediously as her husband does about golf.

It’s not long before Mitsuko, still trying to find a way out of her inner darkness, divorces her tiresome husband and begins to work as a hospital volunteer. To her surprise, she discovers that Otsu continues to “dangle in her heart.” (p. 110) She can’t seem to exorcise him from her thoughts. So when she learns that he’s been priested and is living in Varanasi, she signs up for the India tour, resolving to meet him again. When she does, she finds out that he lives in a Hindu ashram and ministers to dying Hindus who come to Varanasi to be near the sacred Ganges. Scorned by his fellow Catholics and distrusted by many Hindus, Otsu gives himself selflessly to all who need him.

When Mitsuko sees the ministry to which Otsu has dedicated himself, she senses even more strongly her yearning for something to fill the emptiness in her life—“a something that could provide her with a sure sense of fulfilment.” (p. 180) She isn’t sure what it might be. But at novel’s end, we find her talking to a nun, presumably one of Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity, and the implication is that Mitsuko might join them, at least for a time, as a volunteer.

Far from being a once-and-done deal, conversion is an ongoing, lifelong transformation that often advances by fits and starts. As suggested by μετάνοια, the Greek word for conversion, the process pushes one beyond one’s usual way of looking at the world. This is exactly what happens to Mitsuko. She’s no closer to a formal embrace of Christianity or any other religion at novel’s end than she was at its beginning. But her experiences in the intervening years have drawn her ever closer to a lived awareness that “she no longer wanted imitations of love. She wanted real love and nothing else,” (p. 136) the love that both inspires and is fed by service to others.

This insight is vividly expressed in a scene in which Mitsuko bathes in the Ganges, the river of rebirth. As she feels its baptismal-like water flowing around her body, she thinks—or perhaps prays—this:

“I have learned that there is a river of humanity. Though I still don’t know what lies at the end of the flowing river. But I feel as though I’ve started to understand what I was yearning for through all the many mistakes of my past. […] A river of humanity. The sorrows of this deep river of humanity. And I am a part of it.” (pp. 210, 211)

The Archetype of Compassion. There are two Christ figures in Deep River. One is Gaston, the westerner who nursed Tsukada in his final days and helped him to experience forgiveness. The other is Otsu, the “straggler” (p. 183) Japanese priest who, like Endo, eventually discovers that God, like the holy river Ganges, is too expansive to be contained.

In his undergraduate years, both before and after Mitsuko’s efforts to turn him away from God, Otsu was a pretty orthodox Christian. But once in seminary, his growing desire for “a form of Christianity that suits the Japanese mind” (p. 66) raised red flags. His superiors accused him of a nebulous pantheism and he in turn criticized western theologians of slicing God “into categories with their rationality and their conscious minds.” (pp. 117-118) For his part, he was content to bow to the incomprehensibility of God, acknowledging the multiple ways in which the Divine Mystery reveals itself.

“I do not believe that the European brand of Christianity is absolute. […] It seems perfectly natural to me that many people select the god in whom they place their faith on the basis of the culture and traditions and climate of the land of their birth. […] God has many different faces. I don’t think God exists exclusively in the churches and chapels of Europe. I think he is also among the Jews and the Buddhists and the Hindus.” (p. 121)

Despite what Church officialdom views as his dangerous leanings, Otsu manages to get ordained. But his understanding of God is so heterodox that he becomes persona non grata in Catholic circles. He eventually makes his way to Varanasi, where his religious pluralism is acceptable, and commences his ministry of carrying dead and dying Hindus to the Ganges “as if shouldering a Cross.” (p. 162) His compassion for the suffering of others is boundlessly profligate, radically inclusive, universal. “You carried the sorrows of all men on your back and climbed the hill to Golgotha,” he prays as he rises each morning. “I now imitate that act.” (p. 193) And just as with Jesus, the particular manifestation of God to whom he is devoted, Otsu’s compassion eventually costs his life. He’s beaten to death, like a sacrificial “bleating lamb” (p. 212) by a riotous crowd as he tries to save the life of another man from its fury. Like the Lord he serves, Otsu dies a Suffering, because Compassionate, Servant.

Onion-Peeling

In one of his sermons, Paul Tillich summed up the heart of his theological project. God, he argued, is the “infinite and inexhaustible depth and ground of all being.” But because the word “God” often carries disconcerting cultural and personal baggage (not to mention the fact that each of the world’s religions claims a monopoly on it), we should feel perfectly free to chuck it. So, suggests Tillich,

“if the word has not much meaning for you, translate it, and speak of the depths of your life, of the source of your being, of your ultimate concern, of what you take seriously without any reservation. Perhaps, in order to do so, you must forget everything traditional that you have learned about God, perhaps even that word itself. […] He [or she] who knows about depth knows about God.”5

The sacred river Ganges in Endo’s novel symbolizes Tillich’s infinite and inexhaustible of being. As Mitsuko comes to learn, “It’s a deep river, so deep I feel as though it’s not just for the Hindus but for everyone;” to bathe in its waters is to be reborn. (pp. 195, 196, 200) Like the Ganges, God is dynamic, ever flowing, receptive to all creation, embracing within its bosom the endless cycle of life and death. There are as many manifestations of God as there are ripples in the water, and all of them sparkle with vitality.

But Endo offers another God-metaphor as well. At one point in their conversations about God, Mitsuko tells Otsu that she’s uncomfortable with the way he throws around the word “God.”

“Listen, could you please stop using that word ‘God’? It makes me nervous, I can’t relate to it, and it doesn’t mean anything to me.”

“Sorry. If you don’t like that word, we can change it to another name. We can call him Tomato, or even Onion if you prefer.” (p. 63)

There’s humor in this scene, of course. An onion, after all, is a vegetable that evokes pain and tears, and that’s (metaphorically, at least) what Godtalk does to Mitsuko. But there’s a deeper meaning to Otsu's renaming of God.

“All right, then, just what is this Onion to you?”

“God is not so much an existence as a force. This Onion is an entity that performs the labors of love.” (pp. 63, 64)

The curious thing about an onion is that once you begin to peel it back, layer by layer, you get to the point where there’s nothing left. You discover there is no core. Strip away the final innermost layers, and you arrive at …. nothing, no-thing.

This is another way of expressing the inexhaustible and infinite depth of God. God cannot be easily defined because God isn’t just another object. God is no-thing, but instead is a force—the force of love, says Otsu—that penetrates all of reality. In his Tao te Ching, Laozu remarks that the Tao, the force that sustains reality, is like water: it seeps into every crevice, every nook and cranny, until there is nowhere it is not. This is the no-thinged but penetrative God Otsu pledges himself to. For him, it bears the face of Christ. But it can bear many other faces too.

For Endo, the Christianity arrived at by Otsu is compatible, or at least not totally alien, to the Asian temperament. God cannot be constrained in the western theological molds that Otsu criticizes. The river flows on, impervious to definition. The onion offers no theological axiom. But the force of love which God essentially is constantly reveals itself in the meaning-infusing archetypes represented by the five pilgrims in Endo’s tale. These movements of love—Resurrection, Sacrifice, Forgiveness, Conversion, and Compassion—reappear again and again, reminding us of the inexhaustible depth of the many faced God. The river is deep indeed.

###

Shusaku Endo, Deep River, trans. Van C. Gessel (New York: New Directions, 1994), p. 195. Hereafter page references to the novel are indicated parenthetically in the text.

This was the underlying cri de cœur of Endo’s 1966 novel Silence. For Christianity to survive in the East, he concluded, it must abandon its European trappings. “This problem of the reconciliation of my Catholicism with my Japanese blood,” he wrote, “has taught me one thing: that is, that the Japanese must absorb Christianity without the support of a Christian tradition or history or legacy or sensibility.” Quoted in Sonni Efron, “Shusaku Endo; Japanese Novelist, Humorist.” Los Angeles Times (30 September 1996).

Earlier installments of the Presence of Grace series:

Surge, Urbana? J.F. Powers’ Morte d’Urban

Motes and Planks Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood

A Longing for Something We Can’t Name A.G. Mojtabai's Thirst

The Heart’s Deep Longing François Mauriac's Vipers' Tangle

The whole story gestures at the Eucharist—another archetype for Endo?

Paul Tillich, “The Depth of Existence” in The Shaking of the Foundations (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2012), p. 57.