“I have always been mistaken about the object of my desires. We do not know what we desire. We do not love what we think we love.”1

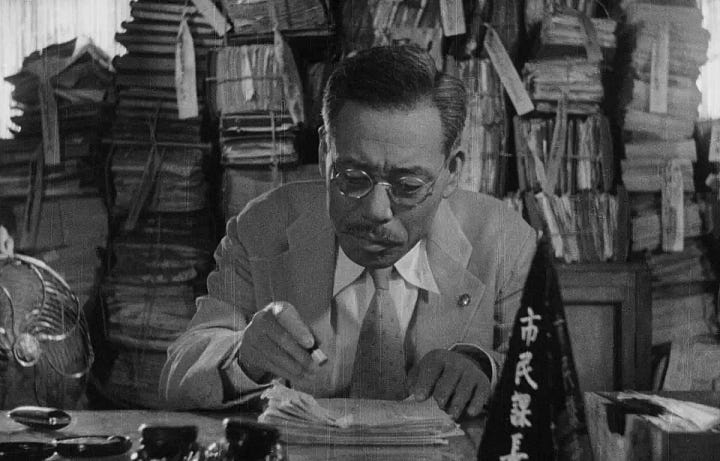

We’re all familiar with the trope of a curmudgeonly old man experiencing, against all odds, a re-birthing conversion. Dickens’ Ebenezer Scrooge or Kurosawa’s Kanji Watanabe are iconic examples. In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge transitions from a bah humbug! miser to a person of genuine warmth and generosity. Watanabe, the drab bureaucrat in Ikiru, breaks through the walls of his rule-bound existence to make sure that underprivileged kids get a playground.

In both cases, the change seems motivated by death-anxiety: the ominous warning of the Ghost of Christmas Future on the one hand and a diagnosis of incurable stomach cancer on the other. But I think something else is going on as well: both Scrooge and Watanabe finally make contact with their longing to love and be loved, the deepest yearning of the human heart. Their discovery re-creates them—or, perhaps more accurately, allows them to consciously be who they were all along, even though they didn’t quite know it.

In this fifth installment of the Presence of Grace series on Catholic novels,2 I explore another story about an aged man’s transformation: Nobel laureate François Mauriac's 1932 Vipers' Tangle. The title is inspired by a line (verse 33) in Matthew 23, the entire chapter of which is Jesus’s condemnation of pharisaical hypocrisy: “You serpents, you brood of vipers, how can you flee from the judgment of Gehenna?” Jesus’s words are an iteration of John Baptizer’s earlier call (Matt 3:7a) for repentance: “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the coming wrath?” As we’ll see, both judgment and repentance play key roles in Mauriac’s novel.

J’accuse!

Except for its final two chapters, Vipers’ Tangle purports to be the journal of Louis, a 68-year-old lawyer dying of heart disease. He’s been alienated from his wife Isa and children Hubert and Geneviève for decades, an estrangement that sentenced him, as he sees it, to an “era of great silence which, for forty years past, has scarcely ever been broken.”3 Poisoned by a lifetime of bitterness, rage, and self-pity, he’s determined to rupture the “great silence” by bequeathing a screed of recrimination and resentment instead of the fortune his presumptive heirs expect. It will be his own lawyerly brief, his posthumous j’accuse testimony against those whom he believes have wronged him.

The bare facts of Louis’ life, recounted by him in his testament, are quickly told.

The only child of uneducated but canny peasants who accumulated land and wealth, he grows up a child “desperate[ly] striving for first place”4 in his schoolwork to compensate for the insecurity of being born on the wrong side of the tracks. He endures a “dreary adolescence,”5 a traditionally difficult developmental period made even more unpleasant for Louis by the fact that most of his peers find him physically and spiritually unattractive. A nose-to-the-grindstone loner at university, he earns a law degree and by dint of brutally hard work—more over-compensation for his personal and social insecurities—soon becomes known as an up-and-coming attorney.

His professional success catches the eye of the Fondaudège family, a clan with a pedigree from the right side of the tracks. He courts their daughter Isa and, mirabile dictu!, she agrees to marry him. For the first time in his life, Louis knows what it is to love and be loved—and this from a woman far superior to him in the social pecking order. He feels affirmed, and in his journal recollects that their first year was ideally happy. The only occasionally dark cloud was Isa’s religiosity. Although his mother had him baptized, Louis has been an avowed freethinker since his university days. He finds religion at best “a boring formality,”6 at worst, shameless hypocrisy.

But his idyllic marriage soon turns sour. One night as he and Isa lie in bed, presumably after making love, she innocently remarks that she had an earlier suitor—one, no less, with the hyper-romantic name of Rodolphe.7 All of Louis’ insecurities—his lowborn background, his unattractiveness and friendlessness, the barely concealed disdain his snooty Fondaudège in-laws have for him—go nuclear to convince him that Isa married him on the rebound without ever really loving or respecting him.

“Less than a year after this great love, how could she have loved me? It was all a sham. She lied to me. I am not set free. How could I have thought that any girl would fall in love with me? I am a man whom nobody can love.”8

This dismal and hasty appraisal builds the wall of silence that separates husband and wife. Furious, humiliated, and profoundly hurt, Louis pulls away from Isa both emotionally and physically. As the years go by, he satisfies his sexual urges with prostitutes and mistresses, and tries to insulate himself from his unhappiness by obsessively vacuuming up as much land, money, and investments as he can. Isa for her part devotes herself single-mindedly to their two children, seeking in them the affection refused her by their father. By the time the dying Louis sits down forty years into their marriage to write his j’accuse, the two have become strangers who just happen to live in the same house. He dwells on one side of the wall, Isa and the two kids (along, eventually, with their own spouses and children) on the other.

Heart Disease and Heart Dis-ease

Louis has suffered for years from heart disease. In his descriptions of the periodic episodes of angina he endures, he describes himself as “choking,” “stifling,” unable to breath, wracked with excruciating pain. His physical heart disease is paralleled by a spiritual heart dis-ease which has its own symptoms: resentment, rage, self-pity, and most of all loneliness. Louis refers to his dis-ease as a “tangle of vipers.”

“I know this heart of mine—this heart; this tangle of vipers. Stifled under them, steeped in their venom, it goes on beating under the swarming of them: this tangle of vipers that it is impossible to separate.”9

At the root of Louis’ heart dis-ease is his frustrated need for love. If we humans didn’t yearn for love, we wouldn’t feel lonely. This is a truth that eludes Louis, blindingly focused as he is on his perceived grievances. Even though he tenderly recalls moments when he experienced fulfillment—with his daughter Marie, who dies while still a child, or his nephew Luc, who perishes in World War I—he’s unable to understand that the emptiness, the loneliness, of his life is because he refuses to acknowledge that what he really desires isn’t wealth, prestige, or vengeance, but to love and be loved. Consequently, he despairingly feels as if his own life, and human existence in general, is meaningless. In an especially poignant cri de coeur, he writes:

“You cannot imagine such a torture as this: to have had nothing out of life, and to await nothing but death—and to feel that there may be nothing beyond this world, that no explanation exists, that the word of the enigma will never be given us …”10

Perniciously, heart dis-ease tends to be infectious. The more Louis refuses to love his family or allow them to love him, the more their own hearts become tangled nests of vipers. As Louis’ physical condition deteriorates, his children and grandchildren, sensing that he’s going to disinherit them, scheme to have him declared legally incompetent. Eavesdropping on their plans one night when they think him asleep, he vents in his journal, so focused on his outraged sense of betrayal that he’s utterly insensible to the catalytic role he’s played in their corruption.

“I had compared my heart with a tangle of vipers. No, no; the tangle of vipers was outside myself. They had gone out of me and rolled themselves together, that night.”11

Ashes

Despite the depth of his heart dis-ease, an awareness on Louis’ part that his life doesn’t have to be the way it is occasionally emerges. He recalls a moment when, captured by the beauty of a twilit landscape, “I suddenly had an intense feeling, an almost physical certitude, that another world existed, a reality of which we knew nothing but the shadow …” The feeling lasted, he writes, “only for an instant.” But it has “repeated itself at very long intervals,” only enhancing its value in his eyes, even though it’s a value whose meaning he doesn’t fully understand.12

Similarly, he encounters people whose very way of being irresistibly assures him that not all people are viperish. I’ve already mentioned Marie and Luc, whose instinctive love of joy and life stirred Louis: “there exists in me a secret chord: that which Marie set vibrating […] and also little Luc.”13 There’s also the young Abbé Ardouin, a Christ-like figure who astounds and touches the outspokenly anti-clerical Louis by uttering “extraordinary words, which I heard for the first time in my life, and which gave me a kind of stupor: ‘You are good.’”14

These intimations of “another world”—of a way of being in which Louis’ yearning for love isn’t choked or stifled by his resentful refusal to love—slowly disentangle his heart, leading to two liberating experiences of judgment and repentance.

The first occurs during a terrific hailstorm. Jarred out of his habitual psychological defenses by the tempest’s violence, Louis finally touches and confesses his hitherto denied yearning for love and reconciliation. Addressing Isa in his journal, he writes,

“Tonight, it seems to me that it is not yet too late to begin our lives over again. What if I do not wait until I am dead to hand over these pages to you? What if I adjured you, in the name of God, to read them to the end? What if I saw you coming back to my room, with your face bathed in tears? What if you opened your arms to me? What if I asked your pardon? What if we fell on our knees together?”15

Although he doesn’t record it, it’s not difficult to imagine that Louis actually does fall on his knees after writing this. That’s because he feels the presence of something holy, something calling him out of himself and beckoning him to a new beginning: “What force is drawing me? A blind force? Love? Perhaps love […] I can no longer deny that a route exists in me which might lead me to your God.”16

The second breakthrough occurs after Isa’s unexpected death. Everyone, including Louis, had supposed he would die first; everyone, including Louis, is shocked by her passing. But Isa must have sensed she was coming to her end, because she burned all her private papers and letters shortly before her fatal stroke. Afterwards, deciphering charred scraps of paper he pulled from the fireplace in her room, Louis recognizes with a shock that Isa had never ceased loving him. Wiping his brow, he leaves a smudge of ash on it from his hand, a clear allusion on Mauriac’s part to the Ash Wednesday rite of judgment and repentance. In that Lenten moment, Louis finally is able to admit and regret his refusal of love and the damage it has inflicted on him and his family.

“I felt, I saw, I had it in my hands—that crime of mine. It did not consist entirely in that hideous nest of vipers—hatred of my children, desire for revenge, love of money; but also in my refusal to seek beyond those entangled vipers. I had held fast to that loathsome tangle as though it were my very heart—as though the beatings of that heart had merged into those writhing reptiles.

It had not been enough for me, throughout half a century, to recognize nothing in myself except that which was not I. I had done the same thing in the case of other people.”17

Louis realizes that what he thought he’d desired—vengeance—wasn’t at all the real object of his desire. It was the not-I, not his real self, that had been calling the shots, and it was the not-them, not the real they, whom he’d considered his enemies. But the scales have been removed, and Louis at long last knows the truth towards which his poor heart had been patiently guiding him for so many years: “We do not know what we desire. We do not love what we think we love.” And in this honest judgment of himself, and in his repentance for the disastrous era of silence created by his pride and self-pity, Louis crosses the threshold of transformation.

A Most Religious Man

Abraham Joshua Heschel once observed that humans have a “terrible loneliness”—what Augustine at the beginning of his Confessions called a restlessness—that makes us wonder if the love for which we yearn is even possible. “Are we alone in the wilderness of the self,” he asks, “alone in this silent universe of which we are a part, and in which we feel at the same time like strangers?”18

It’s precisely this “peer[ing] into the darkness” and “feel[ing] strangled and entombed in the hopelessness of living” that opens us up, says Heschel, to the discovery of the living God.19

This is precisely what happens to Louis.

Even after his experience of judgment and repentance, the insecurity that has been with him since childhood resurfaces to mock him: is it even possible, he asks himself, to change? “What madness, at sixty-eight, to hope to swim against the stream!”20 He recognizes that he needs strength to persevere, and that the source of that strength doesn’t lie within himself, but in “Someone.”

“Yes, Someone in Whom we are all one, Who would be the guarantor of my victory over myself, in the eyes of my family; Someone who would bear witness for me, Who would have relieved me of my foul burden, Who would have assumed it …”21

In the weeks of life remaining to him, Louis does in fact find strength in the Someone whose presence he now senses. There’s no sentimental moment in which he and his children become a Hallmark card family; Hubert and Geneviève remain wary of their father even after he’s deeded all his wealth over to them. His change strikes them as either an unhealthy religious mania or a cover for some nefarious scheme he’s plotting against them.

Nor does Louis suddenly become conventually pious, despite what Hubert and Geneviève think; he continues to keep his distance from formal religion. But he’s cured of the heart dis-ease which plagued him for so many years, and the change in him is apparent to his granddaughter Janine, even if not to others. She sees Louis’ transformation in stark contrast to the empty conventionality of the rest of the family’s Catholicism. For her parents, uncles, aunts, and cousins, religion has little to do with God and nearly everything to do with social propriety. As she bitingly says, “Our thought, our desires, our actions struck no roots in that faith to which we adhered with our lips. With all our strength, we were devoted to material things.”22 Louis, she insists, is “the only religious man I have ever met,”23 someone who at last re-connected with and then embraced (religare = “to bind fast”) humanity’s genuine treasure: the heart’s deep yearning for love and for the Someone Who makes love possible.

Louis dies while writing in his journal. Significantly, the final line he pens alludes to heart pain. On the one hand, his words portend the onslaught of his final attack of angina. But on the other, they gesture at what might be called the saving wound of Love, the wound that allows for Louis’ ultimate rebirth:

“That which stifles me tonight, even as I write these lines; that which makes my heart hurt as though it were going to burst; that love, of which, at last, I know the name ador—”24

The cause of Louis’ death is heart disease and not, thank God, heart dis-ease. The stifling, the burst, is primarily about an overflowing—or, better, an explosion—of love, and only secondarily about angina.

###

François Mauriac, Vipers’ Tangle, trans. Warre B. Wells (New York: Image Books, 1957), p. 167.

Earlier installments of the Presence of Grace series, each of which may be read independently of the others, are linked below.

So, What Exactly Is a “Catholic Novel”?

Surge, Urbane? J.F. Powers’ Morte Urban

Motes and Planks: Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood

A Longing for Something We Can’t Name: A.G. Mojtabai’s Thirst

Vipers’ Tangle, p. 50.

Ibid., p. 20.

Ibid., p. 22.

Ibid., p. 25.

Readers of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary will recall that the character Rodolphe is a suave seducer.

Vipers’ Tangle, p. 44.

Ibid., p. 104.

Ibid., p. 56. The ellipsis is Mauriac’s.

Ibid., p. 128.

Ibid., p. 34. The ellipsis is Mauriac’s.

Ibid., p. 104.

Ibid., p. 76.

Ibid., p. 105.

Ibid., p. 106, 104.

Ibid., pp. 173-174.

Abraham Joshua Heschel, God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (New York: The Noonday Press, 1997), p. 101.

Ibid., p. 140.

Vipers’ Tangle, p. 177.

Ibid. The ellipsis is Mauriac’s.

Ibid., p. 199.

Ibid., p. 194.

Ibid., p. 190.